My bewilderments over the manner in which the FBI creates its raw files began not long after Pearl Harbor. The neat visitor the serge suit scolded me gently for not demanding, in wartime, to see his credentials first. He had come to inquire about Richmond Lattimore '26 of the Bryn Mawr faculty. Yes, I knew him well. We had beer, friends as undergraduates, and had collaborated in a joint first book, HanoverPoems, in 1927. The height of Dick's international repute as the foremost translator of Greek classics lay still some years ahead, but it was clear that my questioner began with no knowledge at all of the norms taken for granted in academic life, nor of the public information concerning the man he was investigating. He might as well have been inquiring about a jockey of my acquaintance. I was only half-braced for the question cited in low gags about the FBI. when he actually sprang it, as if to catch me off guard. Did Lattimore read The Nation or The New Republic? I said I hoped so. My visitor's cardboard calm wrinkled into quite unfeigned astonishment. (My own raw file probably started right there.) I added the commonplace reasons: If you admire them, of course you'll read them; if you distrust them, it's your duty to keep track of what they're up to. This my visitor seemed to regard as double talk. My answers veered toward caution. His annoyance grew.

"All I need to know is," he suddenly exclaimed, "is he a commie? Is he a pinko? Is he a red?"

The exact words, treasured in memory. I said, "No." Dick got his naval commission: Interviews must have been held with infor- mants defter than I had been.

After the war, annoyed by the behavior of the House Committee on Un-American Activities toward screenwriters, and particularly toward authors who sought to combat racism, I drew up a petition urging that the group be abolished and that its "legitimate functions" be turned over to "appropriate standing committees of the House." The document was on my desk to be co-signed by those who came to do so of their own accord. The signers included more than fifty members of the Dartmouth faculty and about a hundred students. The original went to the Speaker of the House of Representatives, a copy to committee chairman J. Parnell Thomas, who must have made it available to the intelligence services.

We had been exercising, of course, our unabridgeable right of petition under the First Amendment to the Constitution - a right certainly abridged if one is harassed in any way for exercising it. Yet all through young Congressman Richard Nixon's hitch on the committee and the high times of McCarthyism that duly followed, the rashness of the petitioners pursued them - and me. Investigators appeared frequently at my office, a few from the armed services, but most from the FBI. Usually they asked if Student X. who had signed the thing, had been just a misguided kid. In view of the shenanigans fostered by the Mundt-Nixon and McCarran Acts, I had come to think of each Student X as more than ever an upright defender of the Constitution. My interrogators never hinted whether they knew that the petition had been drawn up by me. Was I expected to confess? Would praise from the likes of me be a black mark against the young office seeker, who probably had submitted my name, in his innocence, as a reference?

There were two or three light moments. Into the Public Affairs Laboratory of the Great Issues Course, where many current periodicals were kept for research projects, marched an investigator in search of Mr. Boa. After a quick double take I said I expected him shortly. Tom Braden '40, later of the CIA, nowadays a columnist moonlighting as a Dartmouth Trustee, strode in. He was followed, as always, by his huge German shepherd, Jerboa, whom I introduced to our visitor from the FBI. It was all explainable. We who ran the lab had seen nothing amiss in subscribing to The Nation and The New Republic, but had been reluctant to put the name of the College on the mailing list of our choice for an example of vicious racism: Gerald L. K. Smith's TheCross and the Flag. We had had it addressed to J.E.R. Boa, at the lab's post office box.

Who had informed on Boa we never learned, but we forgave him. I suppose that the absence of the name from the College catalogue seemed suspicious to an operative assigned a little later to investigate the Great Issues Course itself. This visitor was solemnly bending over the carbon of my covering letter to Chairman J. Parnell Thomas when he chuckled and remarked that this was the fellow the FBI had just helped send to jail for stealing public funds.

Too many years later another chairman admitted in debate that he did not know What Un-American meant, and took the action we had urged so long ago: He advised the abolition of his own committee, which on February 18, 1969, was voted out of existence.

Well, who were the potential perils to the republic who had provoked such a time-wasting ruckus in what is sometimes quaintly called the intelligence community? Those I active at Dartmouth include Alex Fanell'42, Executive Assistant to the President, who spent many years in the USIA, and Harry Bond 42, Winkley Professor of Anglo Saxon and English Literature, as well as Academic Director of Continuing Education. Among the emeriti hereabouts are Arthur Wilson, recipient of the National Book Award last spring for his definitive life of Diderot, and Don Bartlett '24, a scholar in Japanese studies. Others afar include Maurice Mandelbaum '29, of Johns Hopkins, and the poets Philip Booth '47 at Syracuse and Robert Pack '51 at Middlebury. Scanning these words, perhaps, from on high are Fran Gramlich and Phil Wheelwright, philosophers; physicist Arthur Meservey '06, Librarian Nat Goodrich; and for a zoologist, the deadpan backwoods wit Leland Griggs '02, who shuffled in, bringing a tang of campfires on his plaid jacket, to put an old-fashioned American signature down in rebuke to the Un-Americans. I should like with pride to name them all, who came of their own accord to protest the petty, vindictive scapegoat hunting that was to produce the long shame of the Silent Generation. Alumni here at the time will recognize the variety of the signers from this sample, old and young, liberal and conservative.

The most memorable investigative visit occurred in 1953. President Eisenhower was the Commencement speaker, and a day in advance one of the College's administrators turned up at my study with an FBI man who was checking all rooms overlooking the out-door scene of the exercises. He felt behind books, dumped the waste basket, pulled out desk drawers, hefted my model of the WildWave - a clipper, fortunately, with no little brass guns to let go a possible broadside of curari-tipped brads. Guns! As the two were bowing their way out I had a dreadful memory. Years earlier my small son had brought home a live cartridge traded by a friend. Seeing it, I bethought me of the Smith & Wesson .38, never used, inherited from my father. Small boys might put things together. I had carried the revolver to my study for safer keeping, far back in the shallow central desk drawer, and had forgotten about it.

"Just a minute," I said, and pulled the drawer all the way out. Hidden under some papers, there was the weapon. "You'd better take it," I suggested.

In the whodunits written when I was young and hungry, I denied myself cliches such as, "The blood drained from his face," but this time I saw it happen. Whiteness went down the ruddy brow and cheeks like a drawn window shade. Unable to speak, the sleuth flipped out a big folded handkerchief to pick up and wrap the Smith & Wesson. The President, next day, put aside his ghosted script and ad libbed his "Don't Join the Book Burners" speech. My gun came back on Monday in a blue envelope.

What went into my raw file on this occasion I would still love to know. An FBI man doing his reasonable duty should not have been the one shamed. All the others, inept at a witless routine, had wasted my time and public money. Their kind of questioning could not possibly get useful truth from the very persons whose lives are devoted to the twin jobs of trying to decide what truth is, and then of writing or teaching what seems true. The rawness of information dug out of persons who trust hearsay can only be imagined until the citizen shall have a right established in law to see what has been said about him in secret, and at least to submit his rebuttal.

President Eisenhower rebuked the book burners, and so do I, but as Congress wonders what to do with the alleged millions of dubious dossiers, I hope it will decide that raw files put together in the manner sketched above resemble books about as much as they resemble raw sewage.

Alexander Laing is emeritus Professor ofBelles Lettres. An abbreviated version ofthis article originally appeared in The New Republic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Feature

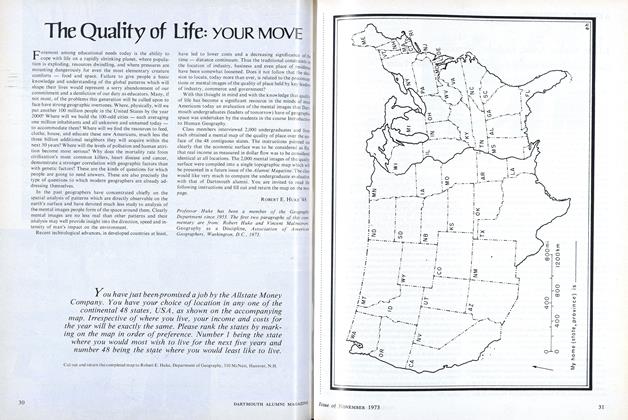

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Feature

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

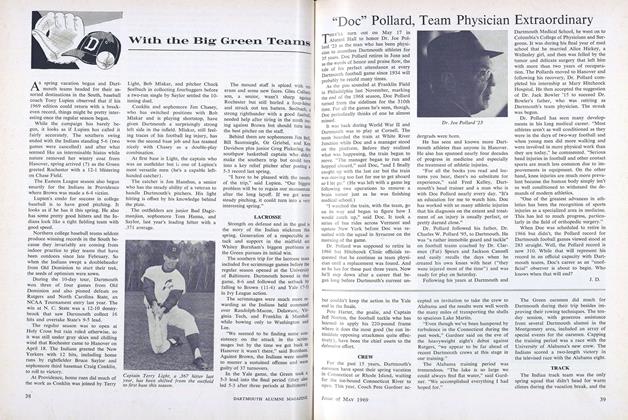

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleEditor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later

November 1973 By HARRIET GUNDERSEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTG.OMERY, C. HALL COLTON

Article

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES APRIL 27 AND 28

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleCharles G. Johnson '71, Oldest Grad, Dies at 99

March 1948 -

Article

Article1951 Fund "Finest Ever"

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleCONCERT SERIES

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

October 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

Article"Doc" Pollard, Team Physician Extraordinary

MAY 1969 By J.D.