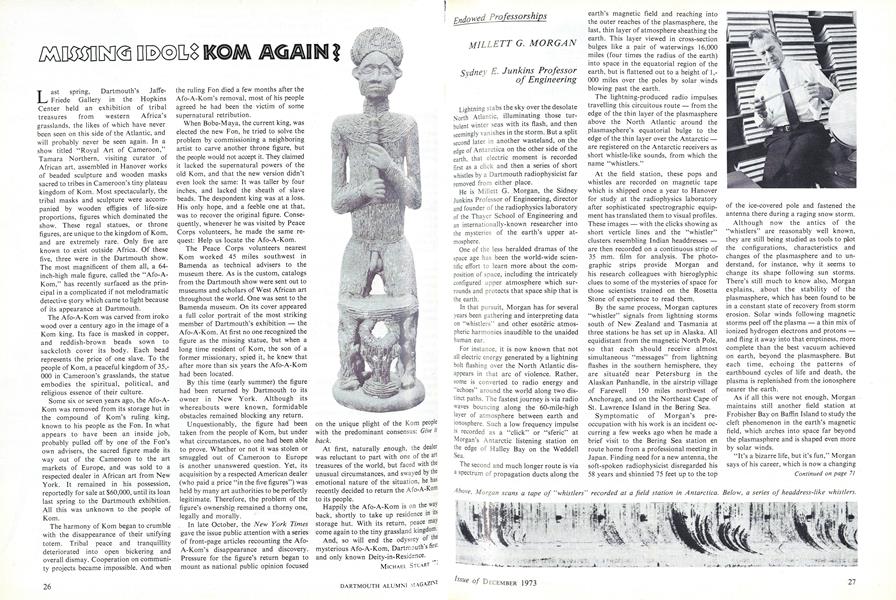

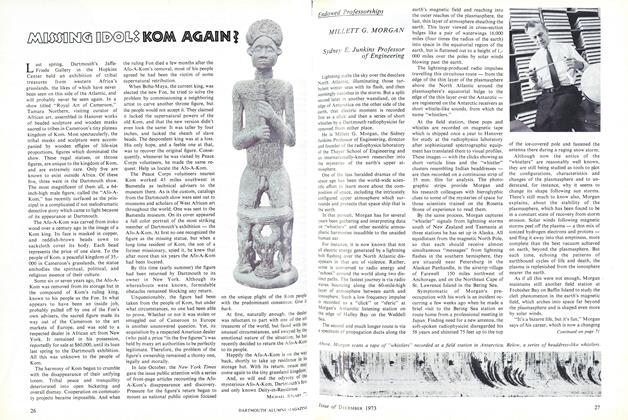

Last spring, Dartmouth's Jaffe- Friede Gallery in the Hopkins Center held an exhibition of tribal treasures from western Africa's grasslands, the likes of which have never been seen on this side of the Atlantic, and will probably never be seen again. In a show titled "Royal Art of Cameroon," Tamara Northern, visiting curator of African art, assembled in Hanover works of beaded sculpture and wooden masks sacred to tribes in Cameroon's tiny plateau kingdom of Kom. Most spectacularly, the tribal masks and sculpture were accompanied by wooden effigies of life-size proportions, figures which dominated the show. These regal statues, or throne figures, are unique to the kingdom of Kom, and are extremely rare. Only five are known to exist outside Africa. Of these five, three were in the Dartmouth show. The most magnificent of them all, a 64- inch-high male figure, called the "Afo-A- Kom," has recently surfaced as the principal in a complicated if not melodramatic detective story which came to light because of its appearance at Dartmouth.

The Afo-A-Kom was carved from iroko wood over a century ago in the image of a Kom king. Its face is masked in copper, and reddish-brown beads sown to sackcloth cover its body. Each bead represents the price of one slave. To the people of Kom, a peaceful kingdom of 35,000 in Cameroon's grasslands, the statue embodies the spiritual, political, and religious essence of their culture.

Some six or seven years ago, the Afo-A- Kom was removed from its storage hut in the compound of Kom's ruling king, known to his people as the Fon. In what appears to have been an inside job, probably pulled off by one of the Fon's own advisers, the sacred figure made its way out of the Cameroon to the art markets of Europe, and was sold to a respected dealer in African art from New York. It remained in his possession, reportedly for sale at $60,000, until its loan last spring to the Dartmouth exhibition. All this was unknown to the people of Kom.

The harmony of Kom began to crumble with the disappearance of their unifying totem. Tribal peace and tranquillity deteriorated into open bickering and overall dismay. Cooperation on community projects became impossible. And when the ruling Fon died a few months after the Afo-A-Kom's removal, most of his people agreed he had been the victim of some supernatural retribution.

When Bobe-Maya, the current king, was elected the new Fon, he tried to solve the problem by commissioning a neighboring artist to carve another throne figure, but the people would not accept it. They claimed it lacked the supernatural powers of the old Kom, and that the new version didn't even look the same: It was taller by four inches, and lacked the sheath of slave beads. The despondent king was at a loss. His only hope, and a feeble one at that, was to recover the original figure. Consequently, whenever he was visited by Peace Corps volunteers, he made the same request: Help us locate the Afo-A-Kom.

The Peace Corps volunteers nearest Kom worked 45 miles southwest in Bamenda as technical advisers to the museum there. As is the custom, catalogs from the Dartmouth show were sent out to museums and scholars of West African art throughout the world. One was sent to the Bamenda museum. On its cover appeared a full color portrait of the most striking member of Dartmouth's exhibition - the Afo-A-Kom. At first no one recognized the figure as the missing statue, but when a long time resident of Kom, the son of a former missionary, spied it, he knew that after more than six years the Afo-A-Kom had been located.

By this time (early summer) the figure had been returned by Dartmouth to its owner in New York. Although its whereabouts were known, formidable obstacles remained blocking any return.

Unquestionably, the figure had been taken from the people of Kom, but under what circumstances, no one had been able to prove. Whether or not it was stolen or smuggled out of Cameroon to Europe is another unanswered question. Yet, its acquisition by a respected American dealer (who paid a price "in the five figures") was held by many art authorities to be perfectly legitimate. Therefore, the problem of the figure's ownership remained a thorny one, legally and morally.

In late October, the New York Times gave the issue public attention with a series of front-page articles recounting the Afo- A-Kom's disappearance and discovery. Pressure for the figure's return began to mount as national public opinion focused on the unique plight of the Kom people with the predominant consensus: Give itback.

At first, naturally .enough, the dealer was reluctant to part with one of the art treasures of the world, but faced with the unusual circumstances, and swayed by the emotional nature of the situation, he ha? recently decided to return the Afo-A-Kom to its people.

Happily the Afo-A-Kom is on the way back, shortly to take up residence in its storage hut. With its return, peace may come again to the tiny grassland kingdom.

And, so will end the odyssey of the mysterious Afo-A-Kom, Dartmouth's first and only known Deity-in-Residence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Feature

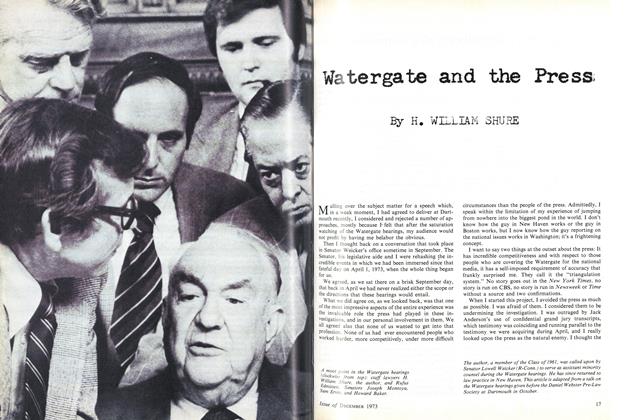

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleMILLETT G. MORGAN

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1973 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER

Features

-

Feature

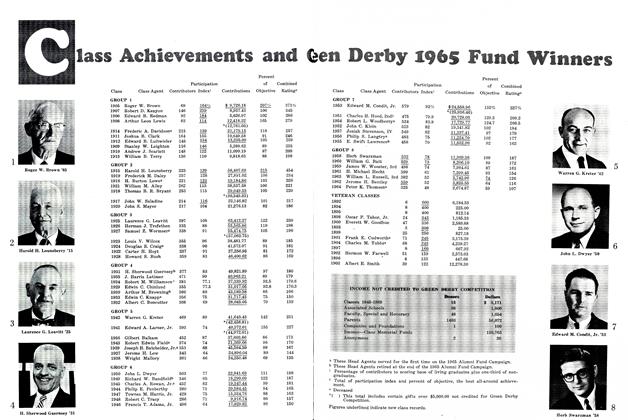

FeatureClass Achievements and Green Derby 1965 Fund Winners

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

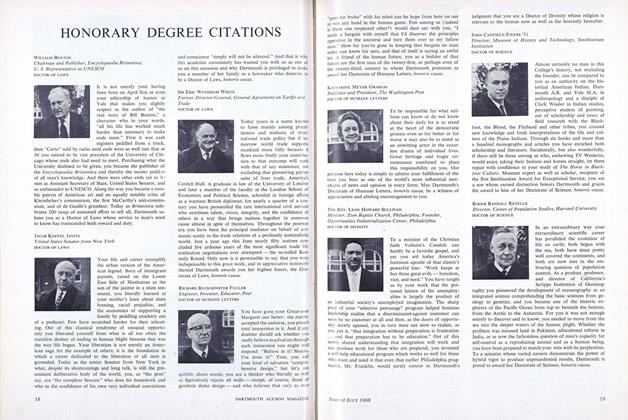

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureReflections

JULY 1966 By FLETCHER R. ANDREWS '16 -

Feature

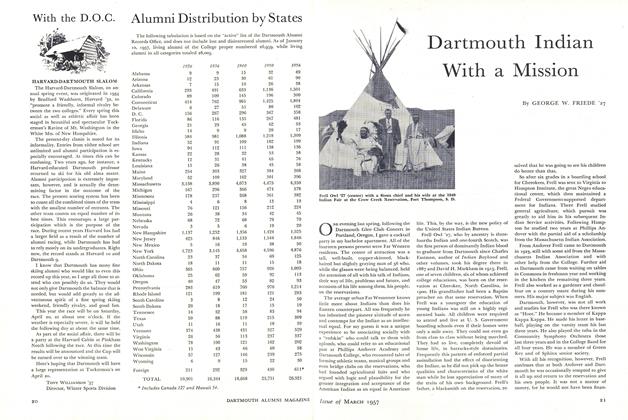

FeatureDartmouth Indian With a Mission

March 1957 By GEORGE W. FRIEDE '27 -

Feature

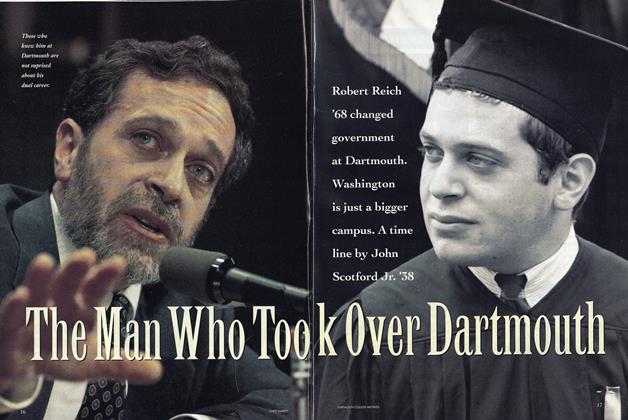

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe Zen of Football

OCTOBER 1988 By Nick Lowery '78