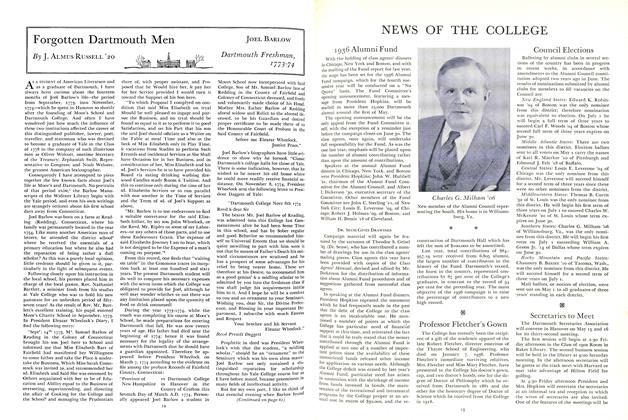

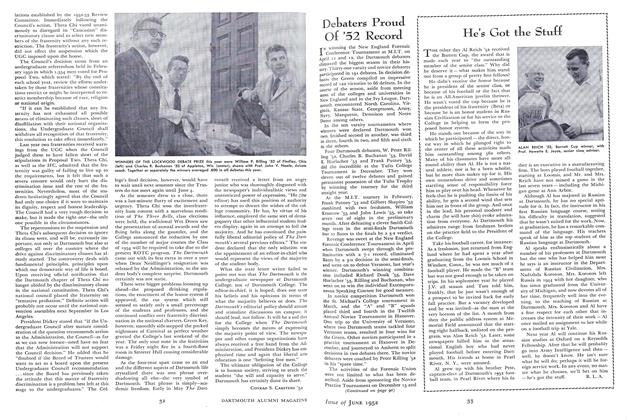

Sydney E. Junkins Professorof Engineering

Lightning stabs the sky over the desolate North Atlantic, illuminating those turbulent winter seas with its flash, and then seemingly vanishes in the storm. But a split second later in another wasteland, on the edge of Antarctica on the other side of the earth, that electric moment is recorded first as a click and then a series of short whistles by a Dartmouth radiophysicist far removed from either place.

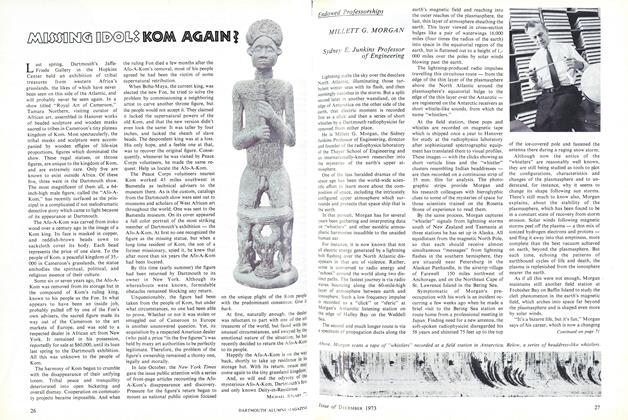

He is Millett G. Morgan, the Sidney Junkins Professor of Engineering, director and founder of the radiophysics laboratory of the Thayer School of Engineering and an internationally-known researcher into the mysteries of the earth's upper atmosphere.

One of the less heralded dramas of the space age has been the world-wide scientific effort to learn more about the composition of space, including the intricately configured upper atmosphere which surrounds and protects that space ship that is the earth.

In that pursuit, Morgan has for several years been gathering and interpreting data on "whistlers" and other esoteric atmospheric harmonies inaudible to the unaided human ear.

For instance, it is now known that not all electric energy generated by a lightning bolt flashing over the North Atlantic disappears in that arc of violence. Rather, some is converted to radio energy and "echoes" around the world along two distinct paths. The fastest journey is via radio waves bouncing along the 60-mile-high layer of atmosphere between earth and ionosphere. Such a low frequency impulse is recorded as a "click" or "sferic" at Morgan's Antarctic listening station on The edge of Halley Bay on the Weddell Sea.

The second and much longer route is via a spectrum of propagation ducts along the earth's magnetic field and reaching into the outer reaches of the plasmasphere, the last, thin layer of atmosphere sheathing the earth. This layer viewed in cross-section bulges like a pair of waterwings 16,000 miles (four times the radius of the earth) into space in the equatorial region of the earth, but is flattened out to a height of 1,000 miles over the poles by solar winds blowing past the earth.

The lightning-produced radio impulses travelling this circuitous route - from the edge of the thin layer of the plasmasphere above the North Atlantic around the plasmasphere's equatorial bulge to the edge of the thin layer over the Antarctic - are registered on the Antarctic receivers as short whistle-like sounds, from which the name "whistlers."

At the field station, these pops and whistles are recorded on magnetic tape which is shipped once a year to Hanover for study at the radiophysics laboratory after sophisticated spectrographic equipment has translated them to visual profiles. These images - with the clicks showing as short verticle lines and the "whistler" clusters resembling Indian headdresses - are then recorded on a continuous strip of 35 mm. film for analysis. The photographic strips provide Morgan and his research colleagues with hieroglyphic clues to some of the mysteries of space for those scientists trained on the Rosetta Stone of experience to read them.

By the same process, Morgan captures "whistler" signals from lightning storms south of New Zealand and Tasmania at three stations he has set up in Alaska. All equidistant from the magnetic North Pole, so that each should receive almost simultaneous "messages" from lightning flashes in the southern hemisphere, they are situate'd near Petersburg in the Alaskan Panhandle, in the airstrip village of Farewell 150 miles northwest of Anchorage, and on the Northeast Cape of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea.

Symptomatic of Morgan's preoccupation with his work is an incident occurring a few weeks ago when he made a brief visit to the Bering Sea station en route home from a professional meeting in Japan. Finding need for a new antenna, the soft-spoken radiophysicist disregarded his 58 years and shinnied 75 feet up to the top of the ice-covered pole and fastened the antenna there during a raging snow storm.

Although now the antics of the "whistlers" are reasonably well known, they are still being studied as tools to plot the configurations, characteristics and changes of the plasmasphere and to understand, for instance, why it seems to change its shape following sun storms. There's still much to know also, Morgan explains, about the stability of the plasmasphere, which has been found to be in a constant state of recovery from storm erosion. Solar winds following magnetic storms peel off the plasma - a thin mix of ionized hydrogen electrons and protons and fling it away into that emptiness, more complete than the best vacuum achieved on earth, beyond the plasmasphere. But each time, echoing the patterns of earthbound cycles of life and death, the plasma is replenished from the ionosphere nearer the earth.

As if all this were not enough, Morgan maintains still another field station at Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island to study the cleft phenomenon in the earth's magnetic field, which arches into space far beyond the plasmasphere and is shaped even more by solar winds.

"It's a bizarre life, but it's fun," Morgan says of his career, which is now a changing mix of teaching, travelling to outpost field stations and studying the visual images of those beeps, blips, hoots and whistles that spontaneously compose nature's unfinished "symphony of space."

His research has also made him an internationally recognized leader in the field, and he is currently a member of the International Relations Committee of the Space Science Board of the National Academy of Sciences.

For the massive scientific effort mounted during the International Geophysical Year (1957-58), Morgan was chairman of the advisory panel on ionospheric physics for the U.S. National IGY Committee and headed the "Whistlers East" program, which made Dartmouth even then a collection point for data on the "whistler" phenomenon. He is a former chairman (1964-67) of the U.S. National Committee of the International Scientific Radio Union, and three years ago, in recognition of his "contributions to international radio science, to engineering and engineering education," was named a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Yet it was almost by chance that Morgan entered the fascinating field of "whistler" research. It started in 1952 when he went to Sydney, Australia, for a professional meeting. There Morgan, already well known in radiophysics, heard a paper on early "whistler" research by a British scientist. Intrigued, he undertook his own studies under a series of grants from the Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation, and it was not long before he had field stations in both the Arctic and Antarctic, complementing the complex radio receiving station he assembled for Dartmouth on his 100-acre farm high on a hill in the sparsely populated Etna section of Hanover.

The son of the late Frank Millett Morgan, a former Dartmouth mathematics professor who with Clifford Clark for many years operated the Clark School in Hanover, Morgan is one of the rare Dartmouth faculty members who are actually natives of Hanover. Growing up on the campus, he learned to ski early by hanging around the ski team when it went out to practice in the late Twenties, and he picked up pointers from Anton Diettrich, Dartmouth's first ski coach. Later, after graduating from Clark School, Morgan went to Cornell, his father's alma mater, in 1933 and there founded and was captain of the Cornell ski team. As an undergraduate skier, he ran the Inferno Race down Mt. Washington's Tuckerman Ravine.

A physics major, ne was graduated with honors in 1937 and received a master's degree in electrical engineering in 1938.

Morgan earned the six-year degree of engineering at Stanford in 1939 and began doctoral studies there, but returned to Hanover in 1941 to help his father run Clark School. His heart, however, was in radio engineering and after a short while he accepted an offer to teach electrical engineering at the Thayer School. One of his students then is a member of the school's current Board of Overseers.

Morgan became director of engineering research in 1949 and founding director of the Radiophysics Laboratory in 1964. He also was a prime mover in the establishment of Thayer School's versatile twotrack doctoral program. He was named the second incumbent of the Junkins chair in 1971, succeeding Biology Professor William W. Ballard '28 on his retirement.

The Junkins Professorship was established in 1963 by a bequest from Sydney E. Junkins '87, for many years the head of a firm of engineers in Winnepeg, Canada, and then consulting engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway. He also had a leading role in the complete electrification of the 108 miles of the Long Island Railroad and directed construction of the Pennsylvania Railway Terminal in New York. He was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Engineering by Dartmouth in 1927.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Feature

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

FeatureMiSSING IDOL:KOM AGAIN?

December 1973 By MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1973 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

FEBRUARY 1973 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45, R.B.G. -

Feature

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJAMES M. COX

April 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHAROLD L. BOND '42

October 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHANS PENNER

May 1975 By R.B.G.