'Oh, yes, I remember typing Gemstone.'

"The only ones who didn't know .. . were the American people."

Mulling over the subject matter for a speech which, in a weak moment, I had agreed to deliver at Dartmouth recently, I considered and rejected a number of approaches, mostly because I felt that after the saturation watching of the Watergate hearings, my audience would not profit by having me belabor the obvious.

Then I thought back on a conversation that took place in Senator Weicker's office sometime in September. The Senator, his legislative aide and I were rehashing the incredible events in which we had been immersed since that fateful day on April 1, 1973, when the whole thing began for us.

We agreed, as we sat there on a brisk September day, that back in April we had never realized either the scope or the directions that these hearings would entail.

What we did agree on, as we looked back, was that one of the most impressive aspects of the entire experience was the invaluable role the press had played in these investigations, and in our personal involvement in them. We all agreed also that none of us wanted to get into that profession. None of us had ever encountered people who worked harder, more competitively, under more difficult circumstances than the people of the press. Admittedly, I speak within the limitation of my experience of jumping from nowhere into the biggest pond in the world. I don't know how the guy in New Haven works or the guy in Boston works, but I now know how the guy reporting on the national issues works in Washington; it's a frightening concept.

I want to say two things at the outset about the press: It has incredible competitiveness and with respect to those people who are covering the Watergate for the national media, it has a self-imposed requirement of accuracy that frankly surprised me. They call it the "triangulation system." No story goes out in the New York Times, no story is run on CBS, no story is run in Newsweek or Time without a source and two confirmations.

When I started this project, I avoided the press as much as possible. I was afraid of them. I considered them to be undermining the investigation. I was outraged by Jack Anderson's use of confidential grand jury transcripts, which testimony was coinciding and running parallel to the testimony we were acquiring during April, and I really looked upon the press as the natural enemy. I thought the writers and broadcasters were really hurting the investi- gation.

But as time progressed, I acquired a respect and admiration for these people and acceptance of their very significant role. I would cite two examples of how Senator Weicker's understanding of the role of the press accomplished the goals that this committee should have been trying to achieve. The first instance came very early in the investigation. On March 23, James McCord was to be sentenced. He gave the now-famous letter to Judge Sirica indicating that people had perjured themselves and that false testimony had resulted in his being convicted. Sirica's response drastically altered the proceedings: "I'm not going to sentence you, or I'm going to provisionally sentence you. You go out and tell the story. You've got a great forum. Go tell the Senate." And so the Senate Committee quickly convened in executive session and started to listen to McCord's testimony on March 28. The committee became obsessed with what we like to call the "Liddy tactic." The members were so preoccupied with McCord's story about what Liddy had done that they forgot that the investigation - or forgot that the whole Watergate affair - was more than a "third-rate burglary."

Weicker was the low man on the totem pole, so there was very little that he could do to re-direct the committee. But on March 28, in an interview with UPI, he said, "We've got to look to the people responsible and I know there are people responsible in the White House for some of the dirty tricks." It was this interview, incidentally, which inspired that famous conversation between John Ehrlichman and Richard Kleindienst - tape recorded by Ehrlichman without Kleindienst's knowledge - when they discussed this "problem" they were having with Weicker. They were upset because they were afraid that Weicker knew about Donald Segretti. When they heard the word "dirty tricks," they assumed that was what Weicker was talking about.

Next, Weicker went before the press in Washington and made a statement that those in the White House responsible for the setting up of the Committee to Re-elect the President ought to be investigated and that that was the direction the investigation should take. A few days later, on April 1, he went on "Face the Nation" and for the first time, he used the name Haldeman. He said that Haldeman was the man in charge of personnel, and that Haldeman was the man that was doing the hiring. Let's ask some questions of Haldeman, he urged.

Three days later Weicker was having breakfast with the editorial board of the Christian Science Monitor. (These breakfasts are a frequent press tool in Washington. The various networks or the various newspapers will get all of their Washington correspondents together and invite aparticular individual to have breakfast with them. Theywill talk sometimes on the record, and sometimes off therecord). During the course of the on-the-record conversation with the Monitor editorial board, Weicker was asked,"Do you think that Haldeman ought to be fired?" TheSenator replied: "I don't think he ought to be fired, I thinkhe ought to resign." Within an hour, every wire service inthe country was reporting that Weicker had demandedHaldeman's resignation. After 24 hours, Senators Ervinand Baker issued a statement that the committee had noevidence indicating that Haldeman had committed any illegal acts. But the interesting result is that the direction ofthe committee changed as of that day and we then began toconcentrate not on the Liddy tactic, but with Magruder,with Haldeman, with the people who were doing the hiring, with the people who were issuing the instructions.Even though Senators Baker and Ervin chastized Weickerpublicly, the fact is the staff" did turn its spotlight ontoareas beyond the seven individuals who happened to breakinto the Watergate.

An interesting result, probably the most dramatic moment of my short-lived career in Washington, came when Terry Lenzner and I decided that we had better call Robert Riesner. We suddenly realized that nobody - the U.S. Attorney, the FBI, or anyone else had interviewed him.

Riesner was Magruder's administrative assistant. He was the one witness who knew the whole story, or at least knew the beginnings of the whole story, and was the one witness capable of opening the flood gates. On April 8, Terry Lenzner and I were sitting with Riesner and his lawyer, when, suddenly, we heard the word "Gemstone." Then we heard about the Gemstone file and the phone call on June 17 from California instructing Riesner to get the file out of the office. We heard about the Gemstone file being brought to John Mitchell. This may not seem so dramatic today, but on April 8, nobody - I mean no one outside the Committee to Re-elect the President - had ever heard the word Gemstone. In the process of following through on this, Terry and I went back to Liddy's secretary, whom we had already interviewed. We went through the whole line of questioning that we had the day or two before and got the same "answers and then one of us just went ahead and said the word Gemstone. "Oh, yes, I remember typing Gemstone," she said. Suddenly, we had a whole new case.

What happened after that is even more interesting- When Magruder was before the committee in public session, he testified that what motivated him to go to the U.S. Attorney and finally tell his whole story about what actually had happened was the fact that he had heard that Riesner had been called to our committee and he knew that once Riesner was called, the truth would be exposed.

So that's one way in which press coverage accomplished what the normal channels or the normal procedures of executive session or senators sitting together or staff sitting together weren't able to do in focusing the investigation where it should be going.

Another example was the Pat Gray story. Pat Gray had, on April 5, announced that he was going to ask the President to withdraw his name as permanent director of the FBI. but by April 25, he was still on as the acting director. Gray and Lowell Weicker had had some contact by virtue of their government roles and the fact that Gray was from Connecticut. On April 25, Gray suddenly called Weicker on the phone and said that he had something very important to tell him. What he had to tell him was that he had been given a file by Ehrlichman and Dean, and that he had interpreted their instructions to mean that he should burn that file. There is an interesting thought with regard to this. On April 25, we had subsequently learned that Dean knew that Gray had destroyed the file. Ehrlichman knew that Gray had destroyed the file. Kleindienst knew it, Peterson knew it, and the President knew it. And really the only ones who didn't know that Gray had destroyed that file were the American people.

I'm not going to speculate as to what that, information was being saved for, or why that information was being concealed, or why that information hadn't become a part of the grand jury investigation at that point. The fact of the matter was that it was being held back and we knew that when the information was to be revealed, it would come out in a way that was going to help nobody but the Administration, which was busy trying to cover itself on all sides. The story has since become history but Weicker, on a Wednesday night, called three people in the press that he knew to be extremely responsible correspondents: Jim Wiehart of the Daily News, Walt Rugaber of the NewYork Times, and Paul Duke of NBC. He told them the Pat Gray story. Eventually, those three people met with Weicker and some of us on his staff two or three times. We went over the story. We rehashed the story. We rehashed the motives of the story and eventually that story was told to the American people. And it was told in a way that we believed brought the truth to the public in a manner that, quite frankly, would be helpful to Pat Gray.

The press fulfilled the role of getting that information to the public. Now the question comes up, why should the press tell these stories? Why get the American people involved? I think the lesson is that somehow when the American people find out what really happened in things like this, the right result comes about. I'm not saying that it always will happen, and I'm not saying it will happen on a timely basis. But somehow, through the history of this country, the more facts the American people have, the more things seem to work out right. This is a theory that I know Senator Weicker follows, and I think it is a theory that a lot of other people now understand as a result of the Watergate hearings.

I remarked to some people at dinner recently that I think the greatest shortcoming that the committee had was the failure to recognize the significance that the press played and could play in this investigation.

Unfortunately, the competitiveness, of the press that I have mentioned caused a literal flood of leaks. But the leak situation really got bad during the course of the hearings because people were fighting to save stories for the hearings and people were fighting to get stories out and various political people were issuing stories because they thought they might be the most helpful to themselves.

Clearly, what the committee should have done and what it never did do was to appoint a press officer. There should have been somebody out there to say that "Today we're interviewing x, y, and z. And today we're going to have in public hearings Mr. Jones, and we expect him to testify as follows. . . ."

This arrangement would have eliminated the speculation, it would have eliminated what inaccuracy there was and it would have given the American people a more proper perspective as to what was coming. It certainly would have kept their interest up. And I don't think that the press would have missed a single story during the course of the hearings.

There is no question that the vast majority of Americans was very much interested in what the committee was doing, at least through the August recess. I think it would have been a lot more beneficial for everyone involved had there been a designated person to point out to the press what was happening and to provide an up-to-date, coherent briefing as to what was transpiring.

But I think the real lesson to be learned out of this, from my perspective, is that cooperation with the press can be very effective to help produce the right results.

In citing the vital role played by the press in helping blast loose the seemingly inpenetrable layers of secrecy and cover-up that shrouded this tragedy, I don't suggest the press is flawless. There are some aspects of vigorous investigative reporting, such as publishing grand jury testimony, that still trouble some people and, indeed, trouble me. But in no way do I want to see any repression of their freedom of inquiry and expression. The free press is indispensable to a free society.

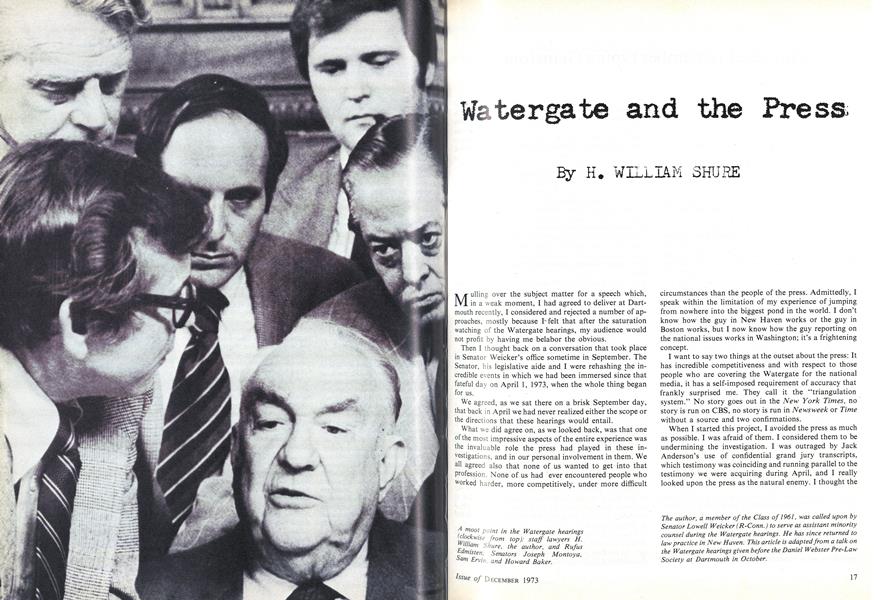

A moot point in the Watergate hearings(clock wise from top): staff lawyers H.william Shure, the author, and RufusEdmislen; Senators Joseph Montoya,Sam Ervin, and Howard Baker.

The author, a member of the Class of 1961, was called upon bySenator Lowell Weicker (R-Conn.) to serve as assistant minoritycounsel during the Watergate hearings. He has since returned tolaw practice in New Haven. This article is adapted from a talk onthe Watergate hearings given before the Daniel Webster Pre-LawSociety at Dartmouth in October.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Feature

FeatureMiSSING IDOL:KOM AGAIN?

December 1973 By MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleMILLETT G. MORGAN

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1973 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER

Features

-

Feature

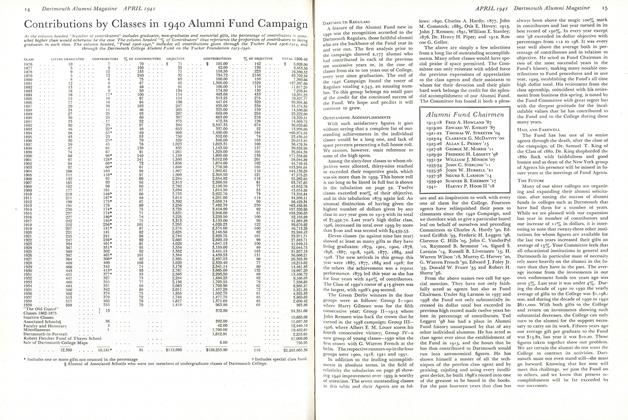

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1940 Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureNugget to Times Square

January 1974 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Report

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Feature

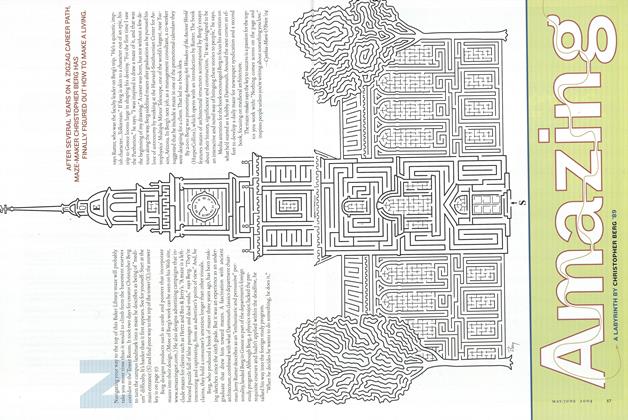

FeatureAmazing

May/June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Feature

FeatureNATO in Trouble

May 1960 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

FEATURE

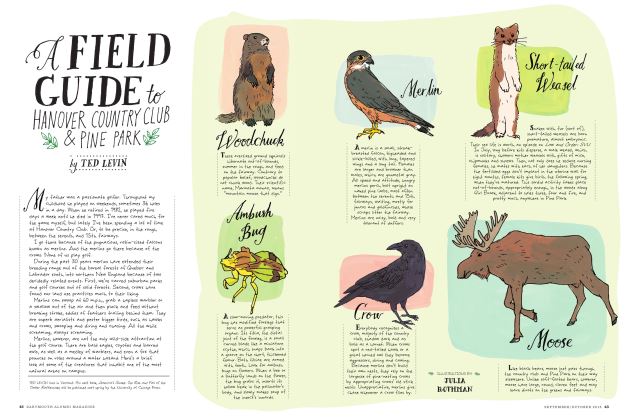

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN