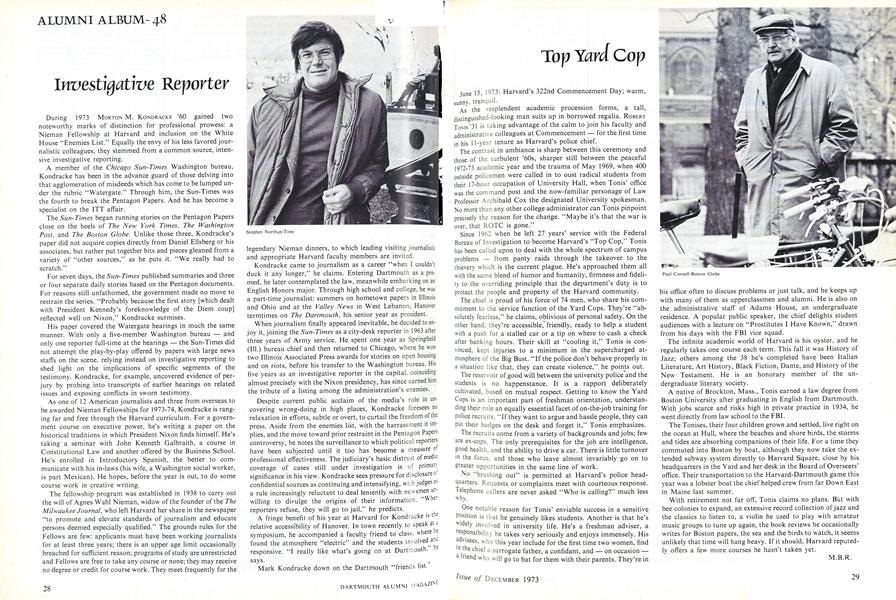

During 1973 MORTON M. KONDRACKE '60 gained two noteworthy marks of distinction for professional prowess: a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard and inclusion on the White House "Enemies List." Equally the envy of his less favored journalistic colleagues, they stemmed from a common source, intensive investigative reporting.

A member of the Chicago Sun-Times Washington bureau, Kondracke has been in the advance guard of those delving into that agglomeration of misdeeds which has come to be lumped under the rubric "Watergate." Through him, the Sun-Times was the fourth to break the Pentagon Papers. And he has become a specialist on the ITT affair.

The Sun-Times began running stories on the Pentagon Papers closeclose on the heels of The New York Times, The WashingtonPost,Post, and The Boston Globe. Unlike those three, Kondracke's paperpaper did not acquire copies directly from Daniel Ellsberg or his associates, but rather put together bits and pieces gleaned from a variety of "other sources," as he puts it. "We really had to scratch."

For seven days, the Sun-Times published summaries and three or four separate daily stories based on the Pentagon documents. For reasons still unfathomed, the government made no move to restrain the series. "Probably because the first story [which dealt with President Kennedy's foreknowledge of the Diem coup] reflected well on Nixon," Kondracke surmises.

His paper covered the Watergate hearings in much the same manner. With only a five-member Washington bureau - and only one reporter full-time at the hearings - the Sun-Times did not attempt the play-by-play offered by papers with large news staffs on the scene, relying instead on investigative reporting to shed light on the implications of specific segments of the testimony. Kondracke, for example, uncovered evidence of perjury by probing into transcripts of earlier hearings on related issues and exposing conflicts in sworn testimony.

As one of 12 American journalists and three from overseas to be awarded Nieman Fellowships for 1973-74, Kondracke is ranging far and free through the Harvard curriculum. For a government course on executive power, he's writing a paper on the historical traditions in which President Nixon finds himself. He's taking a seminar with John Kenneth Galbraith, a course in Constitutional Law and another offered by the Business School. He's enrolled in Introductory Spanish, the better to communicate with his in-laws (his wife, a Washington social worker, is part Mexican). He hopes, before the year is out, to do some course work in creative writing.

The fellowship program was established in 1938 to carry out the will of Agnes Wahl Nieman, widow of the founder of the TheMilwaukee Journal, who left Harvard her share in the newspaper "to promote and elevate standards of journalism and educate persons deemed especially qualified." The grounds rules for the Fellows are few: applicants must have been working journalists for at least three years; there is an upper age limit occasionally breached for sufficient reason; programs of study are unrestricted and Fellows are free to take any course or none; they may receive no degree or credit for course work. They meet frequently for the legendary Nieman dinners, to which leading visiting journalists and appropriate Harvard faculty members are invited.

Kondracke came to journalism as a career "when I couldn't duck it any longer," he claims. Entering Dartmouth as a premed, he later contemplated the law, meanwhile embarking on an English Honors major. Through high school and college, he was a part-time journalist: summers on hometown papers in Illinois and Ohio and at the Valley News in West Lebanon; Hanover termtimes on The Dartmouth, his senior year as president.

When journalism finally appeared inevitable, he decided to enjoy it, joining the Sun-Times as a city-desk reporter in 1963 after three years of Army service. He spent one year as Springfield (Ill.) bureau chief and then returned to Chicago, where he won two Illinois Associated Press awards for stories on open housing and on riots, before his transfer to the Washington bureau. His five years as an investigative reporter in the capital, coinciding almost precisely with the Nixon presidency, has since earned him the tribute of a listing among the administration's enemies.

Despite current public acclaim of the media's role in uncovering wrong-doing in high places, Kondracke foresees no relaxation in efforts, subtle or overt, to curtail the freedom of the press. Aside from the enemies list, with the harrassment it implies, and the move toward prior restraint in the Pentagon Papers controversy, he notes the surveillance to which political reporters have been subjected until it too has become a measure of professional effectiveness. The judiciary's basic distrust of media coverage of cases still under investigation is of primary significance in his view. Kondracke sees pressure for disclosure of confidential sources as continuing and intensifying, with judges as a rule increasingly reluctant to deal leniently with newsmen unwilling to divulge the origins of their information. "When reporters refuse, they will go to jail," he predicts.

A fringe benefit of his year at Harvard for Kondracke is the relative accessibility of Hanover. In town recently to speak at a symposium, he accompanied a faculty friend to class, where he found the atmosphere "electric" and the students involved and responsive. "I really like what's going on at Dartmouth," he says.

Mark Kondracke down on the Dartmouth "friends list."

Stephen Northup-Time

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Feature

FeatureWatergate and the Press

December 1973 By H. WILLIAM SHURE -

Feature

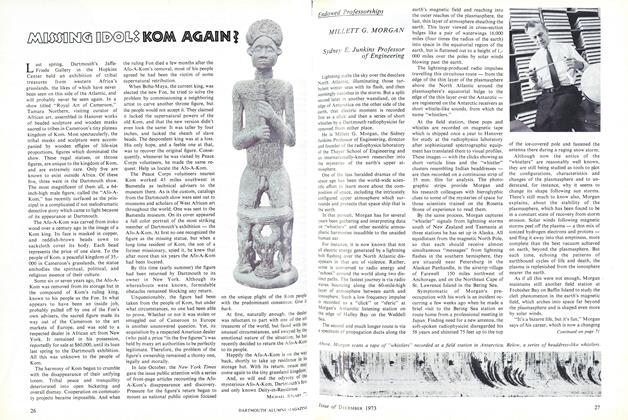

FeatureMiSSING IDOL:KOM AGAIN?

December 1973 By MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleMILLETT G. MORGAN

December 1973 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

March 1954 -

Article

ArticleThe Robert C. Strong Memorial Crafts

December 1960 -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleFRAGMENTS OF TRUTH

October 1935 By Ernest Martin Hopkins '10 -

Article

ArticleSt. Louis

OCTOBER 1971 By HARVEY M. TETTLEBAUM '64 -

Article

ArticleFootball Pact

March 1952 By R. L. Allen '45