Nancy Hedges was a student in my Fall 1972 FreshmanSeminar, "Images of Childhood and Youth." The first writingassignment was to recall or imagine a childhood experience striking enough to cause a change in perception or perspective akind of personal "rite of passage." Nancy's sensitive, sturdilyauthentic sketch was the best of a group of good papers submitted. PROF. THOMAS H. VANCE.

I followed Bompa into the den. I knew he wasn't feeling well and I, too, wanted to get away from the after-dinner cocktails with Philadelphia Cream Cheese and crackers. He poured himself a shot of brandy from a crystal decanter. He sat down in his newly upholstered black leather chair in the corner. The chair lustered like the polished coat of a black stallion. From a silver monogrammed frame his picture smiled at me, with wisps of white hair gently brushing across his tanned, corrugated forehead. The beam of the desk lamp illuminated his face while his ivory gray eyes glistened within half moons. He stood very tall and always tinkled the change in his pockets.

He leaned forward in his chair and held both my hands. I was just as tall as he when I was standing and he was sitting. I smiled slightly, but I knew we were going to be serious this time; he had something important to say. He said he was going to miss me; he would be gone for a month. But when I did meet him in Los Angeles he wanted me to wear my new pink dress and coat with the white butterfly gloves he'd given me. He pulled me closer and whispered that I would even have to wear that embarrassing garter belt to hold up my nylon stockings, if I wanted to look like a princess. I giggled into the rough wool lapel of his herringbone sport coat.

He took out a concealed bag of M & Ms from his pocket; we shut the door and ate them together. He always ate all the blacks, since they were the boys, and I always ate the different colors, since they were the girls. After he had wiped my chocolatey hands with his clean white monogrammed handkerchief, he leaned over and fluttered his eye lashes next to mine for our M & M ritualistic "butterfly kiss."

We rejoined everyone on the porch. But the whole room was filled with smoke and everyone was playing bridge so I got my coat and ran out the door. I started the go-cart as soon as I reached the tool shed. I pretended to be a cab driver, driving a man to the airport. When I got in front of the house, Bompa was sitting on one of the stone steps, laughing because he saw that I was talking to myself. I asked him if he wanted a ride anywhere but he said he didn't, so I sped on toward the airport.

Uncle Peter was driving Nana and Bompa to the Cedar Rapids Airport to catch a flight to Los Angeles. They were planning to spend a month in Palm Springs until I met them in Los Angeles.

That afternoon, after a vigorous game of foursquare, I came home for dinner. I grabbed six Pinwheels and headed for my room, where I could eat in private. Dad intercepted me on the way upstairs and walked silently with me to the room at the end of the hall. I thought he had seen the murky cookies in my hand. When we reached my room, Dad shut the door and I sat down in my new antique rocking chair. He knelt below me and took my stubby fingernailed hands in his. "Your Bompa died this afternoon on the way to the airport." My eyes blurred, I could only weep into the soft cashmere of Dad's sweater.

We all had to go to the mortuary the morning.of the funeral. Mr. Turner asked us to go upstairs to see Bompa's body in the casket. Mom and I stayed downstairs in the waiting room. I sat silently in an old black leather chair with deep cuts and wrinkles marring its surface like a dead war horse's coat.

During the funeral, I sat between my brother and sister in the small side room, reserved for the family. Mom wanted me to wear my dark velvet dress but instead I wore my pink dress and coat, with stockings and white butterfly gloves on. Nana was wearing a black flannel dress with a short matching jacket with three-quarter sleeves. Her hat was black with a lace veil shadowing her face. Dead white candles glowered dimly from the dark burgundy embroidered velvet wall paper and cast shadows upon Bompa's family.

My eyes focused on the wallpaper and I heard the minister praying. Nana's shoulders quivered under the black flannel. I silently leaned forward and gave her my pink silk monogrammed handkerchief to wipe away her tears.

After the funeral, parked cars crowded our street. The living room was filled with stagnant smoke and stagnant faces. I got my coat and ran out the door. I sat for the next hour on our stone steps, eating red, green and yellow M & Ms from a secret pack inside my pocket.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

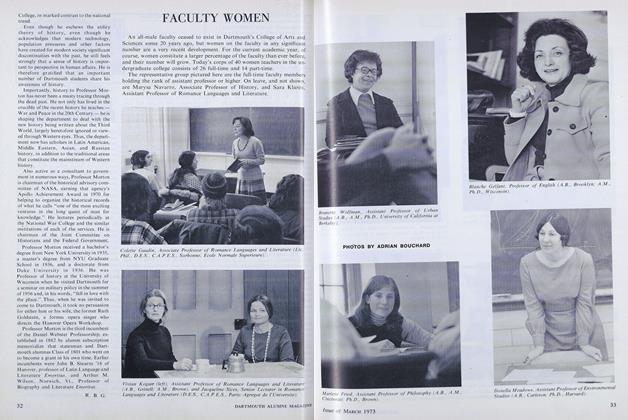

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73