PRISONERS OF PSYCHIATRY: MENTAL PATIENTS, PSYCHIATRISTS, AND THE LAW.

MARCH 1973 ARDEN BUCHOLZ '58Bruce J. Ennis '62. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1972. 232 pp.$6.95.

After three years as a lawyer representing mental patients and from his experiences as a member of the New York Civil Liberties Union Mental Illness Litigation Project, Bruce Ennis has chronicled the case for review and revision of the legal status of mental patients in federal and state law. His essay is illustrated with details from a number of specific cases which the author shepherded through the courts and includes a dissection of the legal philosophy undergirding the current status quo in mental health law.

The author concentrates on four aspects of his topic. First of all, he argues that the definitions of such terms as "mental illness" and "criminally insane" are so vague and ambiguous both in a legal and in a medical sense as to make both terms almost meaningless. However, these poor definitions result in a legal advantage for doctors, clinics, and hospitals and a corresponding legal disadvantage to those patients who fall under the penumbra of these terms. For example, in defining "mental illness," which, as Harry Stack Sullivan wrote, "covers the whole field of inadequate or inappropriate performance in interpersonal relations," the cultural background of the examining physician is crucial: behavior regarded as normal in one culture is often regarded as abnormal in another. Secondly, Ennis argues persuasively that the civil rights of many mental patients are continually violated. For example, persons judged as "criminally insane" or incompetent to stand trial - that is persons accused but not convicted of a crime - are imprisoned without further legal action and often remain behind bars for decades without the opportunity to clear themselves. The judgment of whether a person is competent to stand trial - a legal decision is made by a psychiatrist unschooled in law. More important, Ennis challenges the legality of involuntary confinement, that is confinement against the expressed wishes of the person confined. The principle upon which this is based, confinement for acts which might be committed in the future, is a legal axiom which applies only to mental patients: it is in clear violation of constitutional rights. Thirdly, the author takes up the question of mental hospitals and public accountability. After visits to mental facilities in Florida, Alabama, and New York, Ennis concludes that involuntary mental patients have constitutional rights to adequate treatment, but that in fact many are confined for years with only a brief cursory examination each year and nothing that could be called "treatment." Finally, the author explores the medical and philosophical aspects of mental health, arguing that prolonged hospitalization is anti-therapeutic, that outpatient treatment is both better and cheaper. He cites as one example California, a state which has lower costs and greater success in rehabilitation from a mental health system based around outpatient treatment instead of confinement.

In sum, this is not a legal brief or technical reading for members of Lincoln's Inn. One misses especially the documentation characteristic of some of Ralph Nader's work, which this book in some way resembles. There are no footnotes, index, or bibliography in spite of numerous specific court cases cited by case name, date, court, judge, etc. Nonetheless, Prisoners of Psychiatry is a readable and reasoned exploration of one area we might expect will become an important specialization within the law in the years to come, combining as it does both humanitarianism and the possibility of making a living.

Mr. Bucholz teaches History at the StateUniversity of New York, Brockport.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

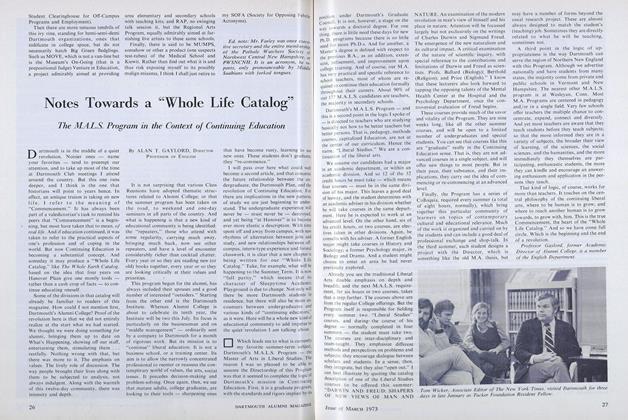

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

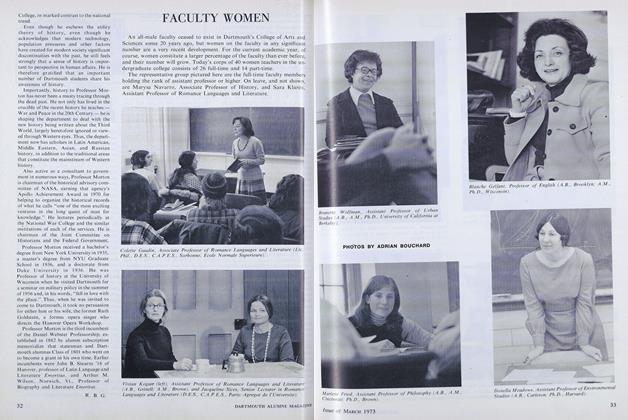

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73

ARDEN BUCHOLZ '58

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January, 1926 -

Books

BooksThe Nuclear Dilemma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By BERNARD D. NOSSITER '47 -

Books

BooksTHE MANAGEMENT OF CYCLICAL LIQUIDITY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS.

APRIL 1968 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL '65h -

Books

BooksTHE MOLLY MAGUIRES.

DECEMBER 1964 By EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16 -

Books

Books"A HAMLET BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCE GUIDE

October 1936 By W. B. Drayton Henderson -

Books

BooksNative Wood-notes

JUNE 1983 By Wilfrid Mellers