The creation of "an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men."

Such was the vision and the will of James Smithson in leaving his considerable fortune to the United States of America in the mid-19th Century. His bequest, accepted largely through the efforts of former President John Quincy Adams over strong opposition from Congressional colleagues, led to the founding of the Smithsonian Institution.

It was this distinguishing mandate to increase as well as diffuse knowledge that first drew WILCOMBE. WASHBURN'48 in 1958 to the Smithsonian, where, after several years as curator of the Division of Political History, he became Director of American Studies in 1965. For Washburn, an ethno-historian, teacher, authority on the American Indian and his long-term relationship with the government, is first and foremost a scholar.

He is also something of a boat-rocker in a profession hardly given to precipitate change, a museum man with a penchant for questioning the objectives and the modus operandi of many of those august repositories of remnants of the world's past. He concedes that his superior occasionally refers to him as "my hair shirt."

In a 1968 article for Museum News, provocatively entitled "Are Museums Necessary?" Washburn argued that museums might better fulfill their responsibilities by converting their collected objects - save for a minimum of specimens unique or typical of period or genre - into well-organized, easily retrievable information and then disposing of them, than by squirreling away multiplying mountains of the objects themselves, which lose verisimilitude with time - and are frequently lost, for any practical purpose, in over-burdened storage facilities.

Concerned more with the active than the passive role of museums, he contends that, of their three traditional functions - repository, medium for popular education, and scholarly tool - the last has more often than not been short-changed. Application of advanced information-retrieval methods, as possible for "libraries of objects" as for libraries of books, would make available for research a vast reservoir of source material, Washburn claims.

As Director of American Studies, relieved of responsibility for exhibits and. so on, he administers a program which cuts across many areas of the Institution's collections, pursues his own investigations, and teaches seminars of qualified graduate students who come to the Smithsonian for specific courses and then return to their home universities for their degrees.

It is the sort of teaching tuned to Washburn's commitment to original research. Far more than in the normal university context, his classes are oriented toward the study of primary source material, rather than interpretation of what other scholars have discovered. "If I can read about a subject in a professional journal," he comments, "so can my students."

Washburn grew up in Hanover, the son of Professor Harold E. Washburn '10. He entered Dartmouth as a V-12 student and, despite three years of Navy service and another as a civilian interpreter in Japan, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cumlaude, winning "D's" in football and track along the way. He took his graduate degrees at Harvard, with a year out for active duty with the Marines-and a year in England on a Reynolds Fellowship, doing research into original documents for his doctoral dissertation on "The Moral and Legal Justifications for Dispossessing the Indians."

The impetus for his interest in the history of the Indian vis-a-vis the government he attributes in part to the year in Japan, his first direct encounter with a different culture; in part to a course in Colonial History at Harvard under Samuel Eliot Morison, who later directed his dissertation.

Of an extensive bibliography in many areas of American History, none of his work has had greater public impact than his studies of the effect on the American Indian of the European cultures which encroached upon his own. His dissertation on the dispossession of the Indian he called "in effect a study of morality ... of what man is, or has been, rather than a study of what he ought to be...." The Indian and the White Man, which he edited, is an ethnohistorical study - a history, with anthropological insights — of the relationship between the Indian and European colonists. His book Red Man's Land/WhiteMan's Law describes "the process by which the Indian moved from sovereign to ward to citizen."

Frequently regarded by all parties as a spokesman for the Indian point of view, Washburn rejects the label of advocate, implying as it may the assumption of a stance followed by a search for evidence to substantiate it. Although his findings have engendered a general sympathy for Indians in their dealings with white men, scholarly objectivity compells him "to follow the truth wherever it leads," however embarrassing to whatever party. He relies on eludication of the facts and public comprehension of what really happened, rather than on petitions, for redress of grievances.

A commitment to "the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men" is as basic a tenet in Wilcomb Washburn's philosophy as it was in James Smithson's.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

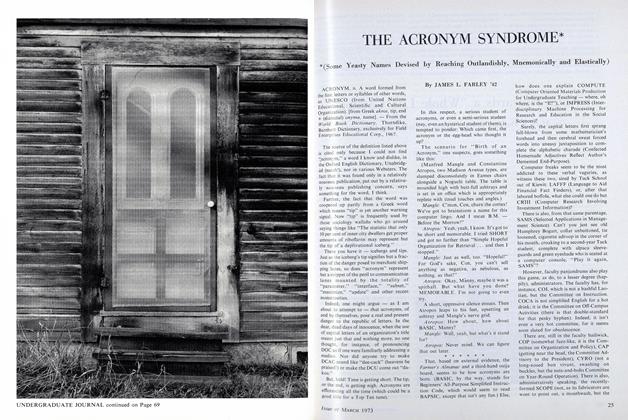

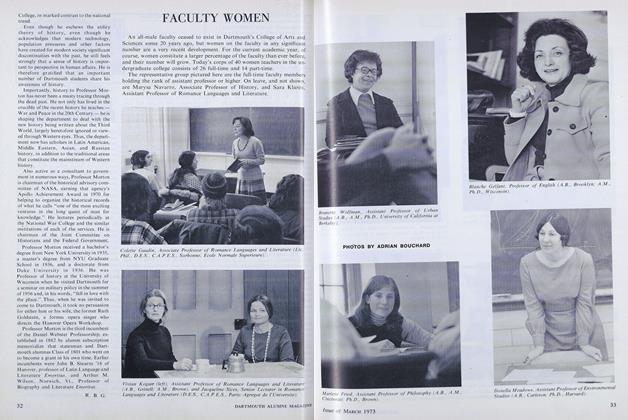

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73