Written for Prof. John Hay's environmental studies course,this piece by Ken Lay '73 offers more than the customary reasonsfor preserving the natural environment.

It seems almost trite, in these days when the masses have taken to the woodlands and the trails, when breast-beating over pollution and the dangers of the burgeoning industrial state has become ever more strident, to try to set on paper what might be called a "conservation ethic." Everybody's doing it, and everybody's missing the point. There is an underlying assumption in most popular concern for the environment that needs examination and rejection. That assumption is that wilderness must be preserved for man. Constantly reiterated is the idea that the death of nature will ultimately mean the death of the human species. Perhaps this is true. Frequently repeated is the idea that life will be exceedingly unpleasant if the rivers and the air are not cleaned up. Perhaps this, too, is true (though I suspect that many people would hardly notice). People point out over and over again that destruction of wild places today will preclude their enjoyment by future generations. This is probably correct, as well. Yet always missing is the only assumption that I feel can be the basis of a real conservation ethic. That assumption is that wild things are good in themselves, intrinsically, and independent of man.

The implications inherent in an acceptance of this notion are tremendous, and worthy of some exploration. Were an intrinsic value in nature to be presumed by those responsible for the care and feeding of our wild lands, gone would be the access roads, the campsites, and the utilities hookups. Gone would be the trail crews, the signs, the maps, the guidebooks, and the rescue squads. Gone, too, would be the afternoon nature hikes, the evening campfire talks, the contracted park concessionaires, and the in-park gas stations filling everything from tires and tanks to baby bottles. At bottom, the assumption of an intrinsic value in nature is elitist. It is an elitism of those willing to accept nature on her own often harsh terms, of those willing to limit their travel to that allowed by the length and strength of their legs, of those who recognize that when nature deals them more than they bargained for that it is upon whatever resources they can muster that they must rely. Finally, and most importantly, it is an elitism that will leave unseen, but undefiled, the frigid valleys of the Brooks Range, the high plateaus and ridges of the Beartooths, and the flower-dappled springtime in Keewatin. This is true conservation.

It is unfortunate that in this, as in all ethics, there is a dilemma. It may be a conceit on the part of environmentalists to think that mankind cannot get along, indeed even exist, without maintaining at least a tenuous relationship with the natural world that bore him. What follows from this idea is that in every man there is the unquenchable desire to "get back to the land." This desire may be the basis of the tremendous movement, after a hundred years of increasing urbanization, that is seeing people scurrying back to the landscape in thousands upons thousands of second homes, miles of trails, myriad campsites on the nation's highways, and in hundreds of outdoor equipment shops. Yet it has become painfully obvious that wilderness in its absolute, uncompromised sense cannot take it. Can it be that this ethic of intrinsic worth in wild things, with its concomitant elitism, will deny to the urban masses the very contact with nature their innermost spirits crave? On the surface it would seem so, but I retain enough optimism to think that wilderness in the relative sense, wilderness as it is perceived by the New York apartment dweller on his walks through Central Park, can satisfy the craving for contact with wild things that threatens to destroy wilderness in its absolute sense. The practical difficulty lies in the violence of disagreement over just how much of that sacrosanct absolute wilderness need be sacrificed to satisfy the popular desire.

Anyone who holds with the intrinsic value concept just set forth could rest comparatively easily if the only threat to wild things was his fellow citizen's passion for a return to the land. But with that same citizen's grasping for economic gain at the expense of remaining wilderness and his insatiable greed for extraction of the nonrenewable bounties of the earth, the lover of nature can make no compromise. The strength and resolve of economic man must not be underestimated, and the strength and resolve of the wilderness elitist must not falter. He will be called a foe 0f progress, an enemy of mankind; indeed, everything from reactionary to radical. Yet he must display an indefatigable assurance of his own virtue, an immense cunning in convincing others of the rectitude of his own position, and the sharpened wit necessary to seize on every blunder his enemy makes and pillory him for it. it is important, too, that he never apologize for his own inconsistencies. He must have no qualms about driving his car to testify against the oil interest! This offends the sensitive, and rightly so but it must never be forgotten that economic man is far more vicious than even this!

Finally, it must be recognized that one threat to absolute wilderness can be used to foil the other. Provision of a relative wilderness in our well-groomed parks to satisfy the urge for a return to our roots could awaken in the majority of our people the desire to preserve, sight unseen, the intrinsic values of our remaining absolute wilderness. It may be here that we will find the political clout necessary to forestall the most violent excesses of economic man. We must seize the club and use it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

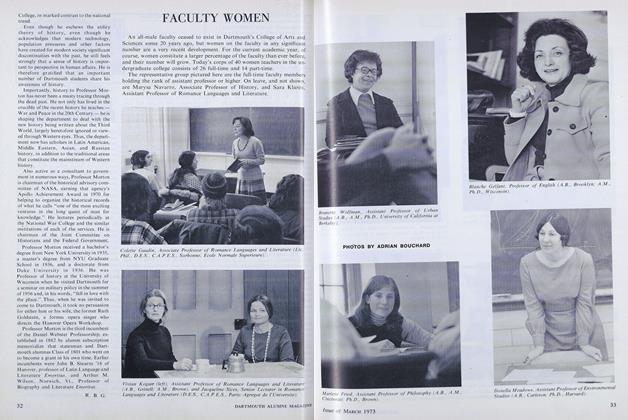

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73

Article

-

Article

ArticleMEL O. ADAMS CABIN IS FORMALLY DEDICATED

August, 1922 -

Article

ArticleOne Night Stands

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleClass of 1993

Sept/Oct 2007 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal Dartmouth in the New Deal

February 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleThe Catcher

OCTOBER 1998 By Gary Libman -

Article

ArticlePASS THE ICED NIETZSCHE

September 1993 By Karen Endicott