THE CABLE CAR IN AMERICA: A NEW TREATISE UPON CABLE OR ROPE TRACTION AS APPLIED TO THE WORKING OF STREET AND OTHER RAILWAYS.

APRIL 1973 EDGAR T. M EADTHE CABLE CAR IN AMERICA: A NEW TREATISE UPON CABLE OR ROPE TRACTION AS APPLIED TO THE WORKING OF STREET AND OTHER RAILWAYS. EDGAR T. M EAD APRIL 1973

By George W. Hilton '46. Cartographby James A. Bier. Berkeley (Calif.):Howel-North Books, 1971. 684 Illustrations.484 pp. $17.50.

I shan't soon forget my first visit to San Francisco a few years prior to World War II. No doubt the lasting impression on a boy had to be the astonishing cable cars, forcing one to consume literally days supervising the turntable operation at Powell and Market, then on invitation to help push the fragile wooden car to where the gripman with his lever could pick up the underground cable. And who could forget those distinctive sounds of the cable system? Even with no car in sight, there were whispered stirrings of the cable making its mad subterranean rounds. The car itself, even well out of view around a curve, could be heard clanging angrily to incautious pedestrians and idiot motorists.

Happilt, the wonders of cableland have been explored by Prof. George Hilton in his The CableCar in America, and I can now talk knowledgably about "rope drops," "gypsies," "slot brakes," and the sinister "Devil's Strip."

At the 1889 peak, there were 59 lines in 29 cities, totaling 360 vertiginous miles. Frisco led with 53 miles, followed by Chicago with 42 and Kansas City with 38. The first practical line in 1873 touched off a massive engineering display, commanding the most advanced of steel, iron, and concrete performances. The intricate design of the cable grip receives an important chapter, so also the wire cable and the track with its complicated underground conduits and unique vertical pulleys. A section deals with ingenious modifications of old cable-car power houses. They became garages , laundries, bowling alleys, and cinemas in later life. A power house in Baltimore was originally a church.

Danger was implicit with cable traction. Here was this cable dragged by an irresistible force circling the city. What would be the feeling of a passenger when a grip gets tangled up in the cable, the car totally unable to stop as it plows nightmarishly through pedestrian crowds, buggies, other cable cars, and even a freight train at a crossing, as happened once in Denver?

By the author's admission, the book verges on becoming a "parade of shortcomings of cable traction." If so, why cable cars at all? Obviously cable cars could clamber up hills and down dales beyond the power of horses. The clincher was that conservative city fathers shied from electricity with its overhead wires, sparks, and threat of electrocutions. But electricity finally won out. and Hilton subtlely dedicates his book to Frank J. Sprague, father of efficient electric traction.

The Panic of 1893 finished off the weaker lines; a few survived for a little while where high volume traffic and electrophobes abounded. Today there is just the spectacular system in San Francisco, prompting the Chronicle's Herb Caen to say "Without cable cars, San Francisco would just be a lumpy Los Angeles." In Hilton's Cable Car inAmerica We have a well illustrated, comprehen- sively documented collector's edition on the technical, social, and financial history of the remarkable cable car.

Mr. Mead is an investment specialist in Hanoverwho has written several books on transportationsubjects.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

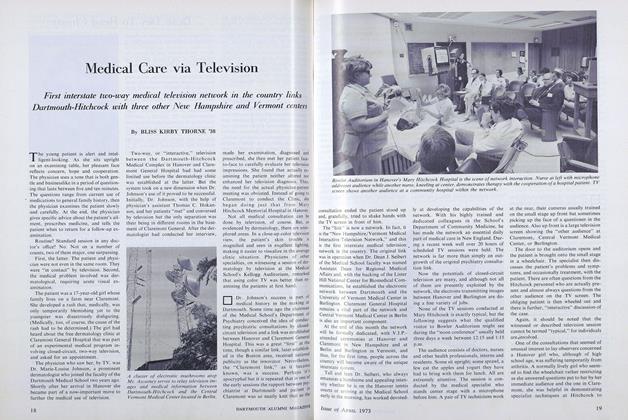

FeatureMedical Care via Television

April 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

April 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureArt Carpenter

April 1973 -

Feature

FeatureHanover Has A Mardi Gras

April 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

APRIL 1965 -

Books

BooksWOMEN, WOMEN, EVERYWHERE.

MAY 1964 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP II '42 -

Books

BooksGhost of Quixote

April 1980 By Frank F. Janney -

Books

BooksFRENCH FOREIGN POLICY DURING THE ADMINISTRATION OF CARDINAL FLEURY, 1726-1743. A STUDY IN DIPLOMACY AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT.

November 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksVIETNAMESE ANTICOLONIALISM 1885-1925.

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Books

BooksEDUCATION AND NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN MEXICO.

FEBRUARY 1968 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR. '57h