In a letter to the editor last month, Mr.Ayers stated that "quite a piece could bewritten" about Ralph Walkingstick '18 andthe Dartmouth Indian Cheer he introducedas an undergraduate. He has been persuadedto write that piece, and it follows.

The furor over Dartmouth's Indian Connection — and the severing of it, if that is what is happening — has a few substantive aspects almost nobody seems to know about. And which have to do a bit with even the way it started in the first place. The one that has intrigued me the most, or certainly the longest, has to do with the now-suppressed indian yells, the ones introduced by that well-remembered Cherokee of the Class of 1918, Ralph Walkingstick. "Stick," as he was called by his boyhood contemporaries, was the elementary and high school chum of my oldest brother. And though he was twelve or thirteen years older, he tolerated me as the junior relation of a good friend. And I knew him well.

Not until my arrival on the Dartmouth campus in the fall of 1925, though, did I know of his escapade in introducing those now famous indian yells. Escapade? Sure, escapade! You see, Stick came out of pre-World-War-I Oklahoma. The state had been Indian Territory until Ralph, and my big brother Joe, were good-sized boys. Even my birth date preceded statehood by some months. That meant the state had been expropriated recently enough from its original owners so that the whites on the scene still figured it a good precaution to view all indians askance. Feeling like the quasi-legal interlopers they actually were, there was more than an occasional uneasiness when indians moved about in groups greater than three or four.

To calm these nervous whites, the new state had requested the United States Indian Service to put a ban, once more, on indians holding what was referred to as their "savage rites." That had been quite cruelly done back in the 1880s. But at this later time, the idea boiled down mainly to forestalling the largest of their oldtime gatherings: their summer-time stomp dances. Most whites, as you can guess, tend to look upon any indian dance as a "war" dance — inciting to frenzy and riot. Actually, the old stomp dances were thoroughly social affairs. Maybe a touch political. Nonetheless and withal, given over to the greatest good feeling and fine fellowship. And the Cherokees particularly thought the restrictions silly. And flouted them openly. Indeed, it shortly became the favorite sport of the young folks, particularly those in attendance at the local indian schools, to treat the school authorities to the wildest possible renditions of their old chants and rallying cries. All of us kids would go into our act for a quick two or three minutes. And then split, as kids today phrase it.

Ralph Walkingstick checked into Dartmouth somewhere near the peak of this pranksome mischief. And nothing was more natural for a high-spirited young buck than to carry on these pleasantries in his new environment. It should not be hard to see also that it was the more enticing to carry them on in this, one of the very bastions of the white establishment. To have several hundred of these very representative young men screaming out our "verboten" old rallying cries, at the top of their lungs, had to have been a satisfying experience.

Apparently it was equally satisfying to the representative young men, youthful exuberance being no narrow racial characteristic. But something further, it contained a large dollop of that old, wild, indian flavor that had lingered traditionally about Dartmouth since its beginnings. And it struck a chord that resonated very strongly across the Hanover plain these now 59 years ago. Moreover, it took the kind of hold that clings and, as the deluge of protest still makes clear, Refuses to be denied. Nor does this one indian think it need be, or should be.

There was one thing lacking though. And possibly it plagued Ole Stick a bit to his dying day. Word of his coup never got back to the government's official indian minions. For that would have crowned everything in triumph. Communications being nothing like they are today, it never happened. And maybe that is a shame. For not only would it have topped the thing off for Stick, but it could, as well, have forced a showdown of sorts over their retention at the College. And it is my seat-of-the-pants conviction that the Dartmouth student body would have risen as one, somewhat in the spirit of the Boston Tea Party, or Ole Dan'l Webster, and told the government's bureaucrats to take their picayune drivel elsewhere. And that kind of embrace would have sealed and cemented Dartmouth's "rights" to those old yells far and beyond all cavil. And forevermore.

It would have had to have happened right then though. For in a very short time thereafter it would not have mattered. For one thing, in the mere eleven years between Stick's and my arrival on campus, the renditions had become close to unrecognizable. The government people would have found no semblance. The truth is, by then the con nection would probably have been caught by no one else but another old sandhill Cherokee. Even "Hoot" Owl, a fellow Cherokee, and the only other indian around at the time, was from the North Carolina band. And therefore not too privy to Oklahoma-grown shenanigans.

But also, in that eleven-year span, an era had passed. Before World War I, indians were still the most visible segment of Oklahoma's population. And a force of sorts in the state's politics. Then came the War. Except, it was not so much the war bringing local upheaval as something coincident to it. The oil boom. That brought massive, on-the-spot changes. It literally up. ended everything and everybody; for whites as much as for indians. The state was swamped by thousands of "entrepreneurs" pouring into this wildcatter's paradise. They either shouldered the older residents aside, or sweet-talked and swindled those to whom they felt they must pander. Indians found themselves reduced to little more than deciduous bands of living curios. And it all took place in less time than was needed to pave the streets of a muddy little prairie town called Tulsa.

The oil boom certainly ended frontier days in Oklahoma. And ushered in gangster days. The more isolated areas of the old Cherokee Nation, being close to impassable, became the favorite hideouts of the likes of Pretty Boy Floyd, Machine Gun Kelly, Ma Barker, the Nash gang, and even Bonnie and Clyde: who touched base there a time or two. Nothing was ever the same anymore. Especially, for indians. The last staunch and solid indian community life, what pockets of it there were left, were obliterated. And exuberance in the youth was never again what anybody would call rife.

For me though, even in 1925, there was no real difficulty in recognizing Stick's coup for what it had been. Naturally, however, Dartmouth's present young indian contingent has no such ties that might bind: no such strands of recognition. Perhaps, though, if they were patiently enough apprised of the fact, the unequivocal fact, that those improbable old yells had authentic beginnings — and full indian sanction, so to speak — they might find a way to be less mean in spirit, and more amenable to" curbing those immature impulses they were so publicly accused of in full-page spread recently. And who knows. They might relent. They might possibly even clamor for a reinstatement. For it never was at all difficult for me to tolerate those somewhat botched-up old yells. Nor even the bogus indian cheerleader. It is true that as an indian I did not identify with him all that well. But in another way, I guess I did too. Because, it seemed to me, one good turn deserved another. Or was it trick or treat? No matter what the principle, I was, and all for it. The only impulse I must confers to is that in later years when I would hear those old yells I was moved to go down ,nd demonstrate their correct rendition. But that obviously would have turned into an ongoing thing. And so a hopeless cause. Maybe, though, if there should blossom a readoption, I would record them, for permanent reference. That should do it. Besides there is an additional laugh or two such an act would provide. Perhaps it should be done anyway. If for nothing else than to pay tribute to Ole Stick's memory.

Samson Occom Revisited

A revisit to Samson Occom, though, and the original Dartmouth Indian Connection, does not contain that much to chuckle over. Although, neither is it the classic tragedy most people now seem to want to make it. Samson Occom's rejection was clearly in the tea leaves. But not the way you keep imagining it. He did, it is unalterably true, raise the astonishingly large lump of money with which the College was founded. And he did, indeed, thereupon get the shaft. But what has got lost is that the whole founding affair could well have been purely a promotion by Occom. And hardly at all the project of Wheelock. That may be hard to believe. But then it has always been next to impossible for whites" to get things right about indians.

First, you have long lost sight of the fact that the indians of that day were not even remotely of a submissive turn of mind. Nor apt to follow anybody's lead too unquestioningly. They were still a monstrously proud people. And by less friendly accounts, even a smugly arrogant one. Either way, whites always seem prone to have assumed their haughty self-esteem to have been largely empty pose. And that indians really must have known they were goners from the instant Columbus put ashore. That is dead wrong. Maybe they ought to have. But they did not.

Secondly, to my mind what should always have been clear, but never was, indians were least of all ever intellectually intimidated by you whites. It had not taken them any time at all to realize you palefaced outlanders were going to pose a problem. Yet for the longest time, there was not a shadow of a doubt, certainly not among the more potent tribes, that they were, and would continue to be, able to contend with you. Particularly if it came to a crunch. That you might carefully avoid bringing things to a crunch until it became a lead-pipe cinch may have escaped them. They may not have thought you were that smart. Whatever the case, indian cocksureness did not even begin to crumble until along after Tecumseh's fall.

The Cherokees, for example, during all this time, thought themselves eternally impregnable, as they had been for centuries, in their southern appalachian mountain fastnesses. And when Tecumseh came to solicit their support in his pan-indian alliance — the prospect of which frightened the living daylights out of the total white population — the Cherokees pooh-poohed him. He was invited instead to come and live with them. And thus to put himself, and all the indians he chose to bring with him, out of danger. Less than thirty years later those same Cherokees were being herded across the country like so many cattle, to the aforementioned Indian Territory. The time for the crunch had become propitious.

But getting back to Dartmouth: It has certainly been a mistake to picture Occom as the Tonto-like disciple of Eleazar Wheelock. He was easily as much his own man as the far more flamboyant Joseph Brant, another prime aboriginal figure in the dramatis personae of Dartmouth's founding. Brant too advocated a separate and special institution for indians. But his idea was to keep it more apart from the ecclesiastic aegis. Essentially though, every broad-gauged indian of that time, and there were many, was speculating on what might be the means of bringing about a decent and viable coexistence, indians with whites. And a forum where the adjudication of the collective better parts of both cultures might be pursued was a natural. But for indians. Whites saw no need of such a thing at all.

Nor is there any overpowering evidence that Wheelock and Occom were ever as close as people like to think they must have been, to collaborate on the founding of a college. And something perhaps even more impossible to countenance: all the indians to attend Wheelock's schools were quite well educated before they ever got to him. That is, as indians. For few whites have ever had any notion of the degree of what now would be called infancy training, which was standard with the indians. The full liturgy of the tribe, for instance, would have to be memorized, word for word, by the time each child was six or eight. Then, they would be expected to be able to recite it all back, verbatim and with gestures. With no set system of writing, this is rather obviously the only way it could be conserved and passed down. But the clear purpose of that early an exercise was pointedly the training of the mind. And not simply its perpetuation.

You still may not quite grasp the enormity of that practice. But perhaps you can if it is put this way: If every white child had to absorb the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, all the Amendments, and every landmark decision of the Supreme Court, and this by the time the fourth grade had ordinarily been reached, you would have a close parallel. And you can see such training would not produce mousy people. Nor did it then produce people with small capabilities at organizing their thought. People marvel at the many preserved comments of the indians of that day. And of those both earlier and later. The deep insight, the broad and comprehensive grasp of their minds; most often those qualities seem to have been regarded rather as freaks of nature. Hardly. They were the result of just about as careful a regimen of cognitive stimulation as man has ever devised. And neither Dartmouth nor any other college has ever averaged out even close to the same overall effectiveness.

So please accept the premise that the very special indian exclusivity planned for Dartmouth was totally the dream of Samson Occom. An all-indian school may well have been something Wheelock would have gone along with. But not an all-indian curriculum. And when he found out, too late, that Occom was casting about for a way to interleave what he, Occom, looked upon as the intellectual sphere of the indian, along with the intellectual sphere he granted the white man, it became a no-go situation. For actually, coexistence of the sort indians were looking for was no more in the mind of Eleazar Wheelock than it was in, say, Cotton Mather's. His tremendously greater fellow feeling notwithstanding.

There is simply no question though, that Eleazar Wheelock was irresistibly attracted to this native people of such great natural reserve and primitive dignity. And he did, in simple fact, devote the major portion of his life to conferring upon them, the likeliest of heathen, what he devoutly regarded as the basis for the most profound dignity possible to man. You have to doubt his very sincerity to detract from that. I cannot. I like to picture him as a man whose efforts on behalf of indians were so far above, and so far beyond, what was in the works everywhere else for indians, that if he did not bat a thousand, a five hundred average is quite respectable.

But Samson Occom batted five hundred too. And he took his lumps like a man. Both these historical figures deserve to stand high in Dartmouth's traditions. Simply allow me to end on the note that in your search for the key to Occom's admissions policy, I am as baffled as you are. And even if you never quite find it, bless you for trying. And for taking the guff that goes along with the effort.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

May 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

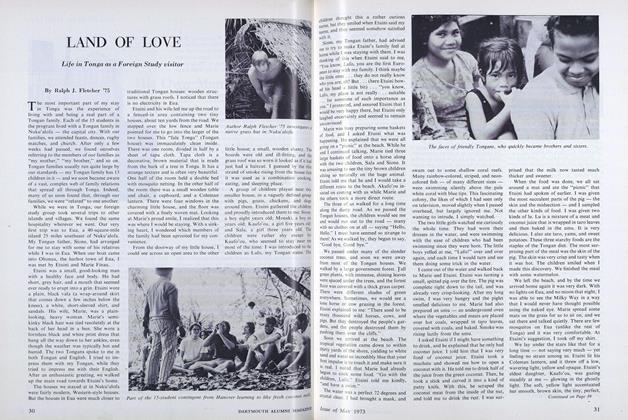

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

May 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75 -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

May 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

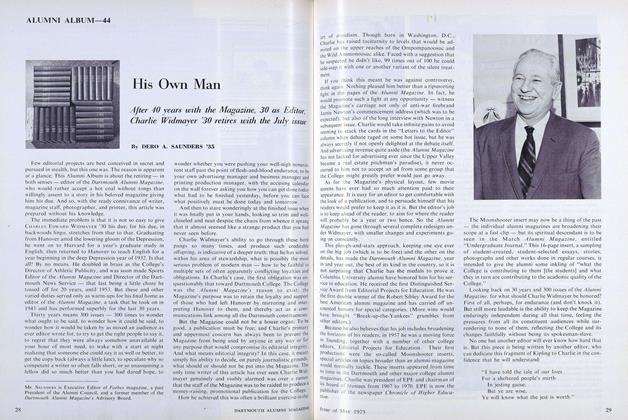

ArticleHis Own Man

May 1973 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

May 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, JOHN T. AUWERTER