Life in Tonga as a Foreign Study visitor

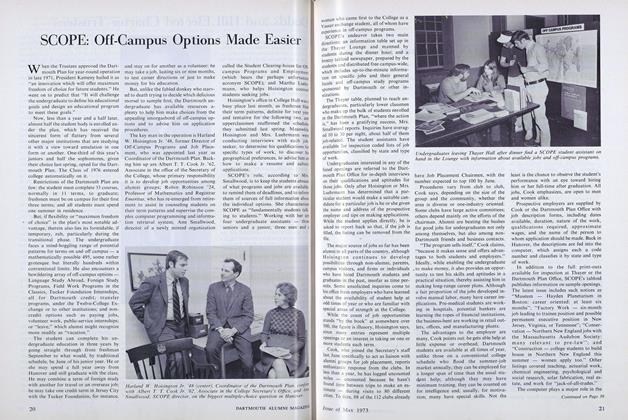

The most important part of my stay in Tonga was the experience of living with and being a real part of a Tongan family. Each of the 15 students in the program lived with a Tongan family in Nuku'alofa — the capital city. With our families, we attended feasts, dances, rugby matches, and church. After only a few weeks had passed, we found ourselves referring to the members of our families as "my mother," "my brother," and so on. Tongan families usually run quite large by our standards — my Tongan family has 13 children in it — and we soon became aware of a vast, complex web of family relations that spread all through Tonga. Indeed, many of us soon found that, through our families, we were "related" to one another.

While we were in Tonga, our foreign study group took several trips to other islands and villages. We found the same hospitality wherever we went. Our very first trip was to Eua, a 40-square-mile island 25 miles southeast of Nuku'alofa. My Tongan father, Sione, had arranged for me to stay with some of his relatives while I was in Eua. When our boat came into Ohonua, the harbor town of Eua, I was met by Etuini and Marie Finau.

Etuini was a small, good-looking man with a healthy face and body. He had short, grey hair, and a mouth that seemed ever ready to erupt into a grin. Etuini wore a plain, black vala (a wrap-around skirt that comes down a few inches below the knees), a white, short-sleeved shirt, and sandals. His wife, Marie, was a plain-looking, heavy woman. Marie's semikinky black hair was tied resolutely at the back of her head in a bun. She wore a formless black and white print dress that hung all the way down to her ankles, even though the weather was typically hot and humid. The two Tongans spoke to me in both Tongan and English. I tried to impress them with my Tongan, while they tried to impress me with their English. After an enthusiastic greeting, we walked up the main road towards Etuini's home.

The houses we stayed at in Nuku'alofa were fairly modern. Western-style houses. But the houses in Eua were much closer to traditional Tongan houses: wooden structures with grass roofs. I noticed that there is no electricity in Eua.

Etuini and his wife led me up the road to a fenced-in area containing two tiny houses, about ten yards from the road. We stepped over the low fence and Marie pointed for me to go into the larger of the two houses. This "fale Tonga" (Tongan house) was immaculately clean inside. There was one room, divided in half by a sheet of tapa cloth. Tapa cloth is a decorative, brown material that is made from the bark of a tree in Tonga. It has a strange texture and is often very beautiful. One half of the room held a double bed with mosquito netting. In the other half of the room there was a small wooden table and chair, a cupboard, and a Coleman lantern. There were four windows in the charming little house, and the floor was covered with a finely woven mat. Looking at Marie's proud smile, I realized that this was where I would be staying. With a sinking heart, I wondered which members of the family had been uprooted for my convenience.

From the doorway of my little house, I could see across an open area to the other little house; a small, wooden shanty. The boards were old and ill-fitting, and the grass roof was so worn it looked as if it had just had a haircut. I guessed by the thin strand of smoke rising from the house that it was used as a combination cooking, eating, and sleeping place.

A group of children played near this smaller house, in a vaguely defined group with pigs, goats, chickens, and dogs around them. Etuini gathered the children and proudly introduced them to me: Sione. a boy eight years old; Moeaki, a boy six years old; Kaufo'ou, a girl five years old: and Sala, a girl three years old. The children were rather shy except for Kaufo'ou, who seemed to stay near me most of the time. I was introduced to the children as Lafo, my Tongan name. The childre thought this a rather curious name but they smiled when Etuini said my name and they seemed somehow satisfied with it.

Sione, my Tongan father, had advised me to make Etuini's family feel at home while I was staying with them. I was thinking of this when Etuini said to me, "You know, Lafo, you are the first European to stay with my family. I think maybe [he little ones ... they do not really know who you are, eh? But... (here Etuini bowed his head a little bit) ... "you know, Lafo, my place is not really ... suitable for someone of such importance as you." I protested, and assured Etuini that I would be very happy there, but Etuini only laughed uncertainly and seemed to remain unconvinced.

Marie was busy preparing some baskets of food, and I asked Etuini what was happening. He explained that we were all going on a "picnic" at the beach. While he and 1 continued talking, Marie tied three large baskets of food onto a horse along with the two children, Sala and Sione. It was amusing to see the tiny brown children sitting so naturally on the huge animal. Etuini told me that he and I would take a different route to the beach. Akufo'ou insisted on coming with us while Marie and the others took a more direct route.

The three of us walked for a long time along the dusty road. As we passed the Tongan houses, the children would see me and would run out to the road - many with no clothes on at all - saying "Hello, Hello." I must have seemed so strange to them! As we walked by, they began to say, "Good bye, Good bye."

We passed under many of the slender coconut trees, and soon we were away from most of the Tongan houses. We walked by a large government forest. Tall green plants, with immense, shining leaves were spaced under the trees, and the forest floor was covered with a thick grass carpet. There' were different shades of green everywhere. Sometimes, we would see a lone horse or cow grazing in the forest. Etuini explained to me: "There used to be many thousand wild horses, cows, and Pigs. But they destroyed the people's gardens, and the people destroyed them by Pushing them over the cliffs."

Soon we arrived at the beach. The tropical vegetation came down to within thirty yards of the shore, yielding to white sand and water so incredibly blue that your first impulse is to touch it and make sure it is real. I noted that Marie had already begun to cook some food. "Go with the children, Lafo," Etuini told me kindly, and have a swim."

The water was a perfect 72 degrees and crystal clear. I had brought a mask, and swam out to some shallow coral reefs. Many rainbow-colored, striped, and neoncolored fish - of many different sizes were swimming silently above the pale white coral with blue tips. This fascinating colony, the likes of which I had seen only on television, moved slightly when I passed overhead, but largely ignored me. Not wanting to intrude, I simply watched.

The two little girls watched me curiously the whole time. They had worn their dresses in the water, and were swimming with the ease of children who had been swimming since they were born. The little boys yelled at me, "Lafo!" over and over again, and each time I would turn and see them doing some trick in the water.

I came out of the water and walked back to Marie and Etuini. Etuini was turning a small, spitted pig over the fire. The pig was complete right down to the tail, and was already very crisp-looking. After my long swim, I was very hungry and the piglet smelled delicious to me. Marie had also prepared an umu - an underground oven where the vegetables and meats are placed over hot coals, wrapped in taro leaves, covered with coals, and baked. Smoke was rising lazily from the umu.

I asked Etuini if I might have something to drink, and he explained that he only had coconut juice. I told him that I was very fond of coconut juice. Etuini took a machete and showed me how to open a coconut with it. He told me to drink half of the juice from the green coconut. Then, he took a stick and carved it into a kind of putty knife. With this, he scraped the coconut meat from the inside of the nut, and told me to drink the rest. I was surprised that the milk now tasted much thicker and sweeter.

When the food was done, we all sat around a mat and ate the "picnic" that Etuini had spoken of earlier. I was given the most succulent parts of the pig — the skin and the midsection — and I sampled the other kinds of food. I was given two kinds of lu. Lu is a mixture of a meat and coconut juice that is wrapped in taro leaves and then baked in the umu. It is very delicious. I also ate taro, yams, and sweet potatoes. These three starchy foods are the staples of the Tongan diet. The most surprising part of the meal was the skin of the pig. The skin was very crisp and tasty when it was hot. The children smiled when I made this discovery. We finished the meal with some watermelon.

We left the beach, and by the time we arrived home again it was very dark. With no lights on Eua, and no moon that night, I was able to see the Milky Way in a way that I would never have thought possible using the naked eye. Marie spread some mats on the grass for us to sit on, and we sat there and talked quietly. There are few mosquitos on Eua (unlike the rest of Tonga) and it was very comfortable. At Etuini's suggestion, I took off my shirt.

We lay under the stars like that for a long time — not saying very much — yet feeling no strain among us. Etuini lit his Coleman lantern, and it threw off a low, wavering light, yellow and opaque. Etuini's eldest daughter, Kaufo'ou, was gazing steadily at me — glowing in the ghostly light. The soft, yellow light accentuated her smooth, brown skin, the tiny, perfect, white teeth, and her shining, braided, dark hair. The soft fragrance of coconut oil reached me from her hair. Lying there like that, looking at me with her deep, black eyes, Kaufo'ou seemed more like the offspring of a god than an ordinary child. And the ragged but very clean white pajamas that she wore only added to that impression.

Suddenly, Etuini spotted a satellite moving overhead. All of us watched the glowing, moving dot in amazement. "Did the Americans or the Russians send that satellite into space?" Etuini wanted to know. I didn't know. For a moment, I became patriotic and started speaking about the American landing on the moon. The Tongans listened respectfully for awhile, but I suddenly stopped. I suddenly felt far, far away from the term "satellite," and from the nation that puts them into space. It was a singular joy for these Tongans to watch the moon, their moon rise every evening. These Tongans also watched the rich American tourists come to Tonga and buy everything in sight. Was I supposed to tell them that the Americans had bought their moon, too?

While I was thinking, Etuini began to speak about the night the Americans tested the hydrogen bomb on Bikini Island. "At night, the sky became very red we were all very afraid. Some people were running through the villages and saying the world was going to end. And later on, the sky turned a strange green color and many other colors." I shivered at his words, even though it was a warm evening. After more talking, we went to bed. Etuini insisted that I sleep in the double bed while he slept on the floor.

The next day, Marie gave me a beautiful tapa cloth as a souvenir of my stay with her family. I photographed the family, exchanged addresses with Etuini, and ran to catch the boat back to Nuku'alofa. Just as I was approaching the boat, Kaufo'au came running to me, and put a new, white flower lei around my neck. I thanked her and shyly kissed her good bye.

"Eua" literally means "there will be shelter." I know that when I return to Eua, as I intend to, there will be shelter for me. "Nuku'alofa" means "the land of love." That name, too, is very appropriate. Let me quote the letter that my Tongan father sent to my American one. "I leave Lafo to tell our story for you to hear, and I think he shall show you the real picture of Tongan customs and love. Although this is the tiniest kingdom in the world, our love is quite warm. This is a very poor island, but our hospitality and friendship are quite real."

All of which, somehow, makes up more than just a foreign study program.

Author Ralph Fletcher '75 investigates anative grass hut in Nukualofa.

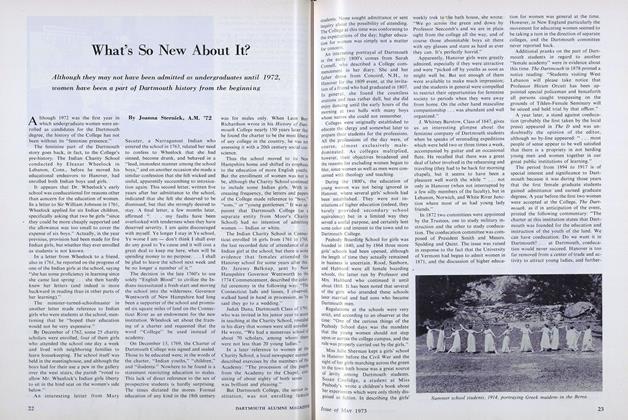

Part of the 15-student contingent from Hanover learning to like fresh coconut milk.

The faces of friendly Tongans, who quickly became brothers and sisters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

May 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

May 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Yell Revisited

May 1973 By Russell O. Ayers '29 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

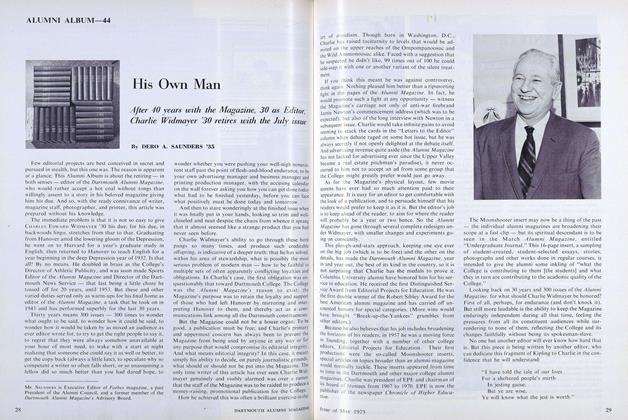

ArticleHis Own Man

May 1973 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

May 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, JOHN T. AUWERTER

Features

-

Feature

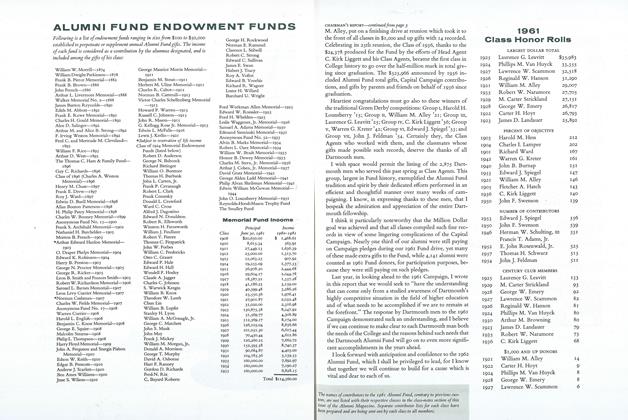

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1961 -

Feature

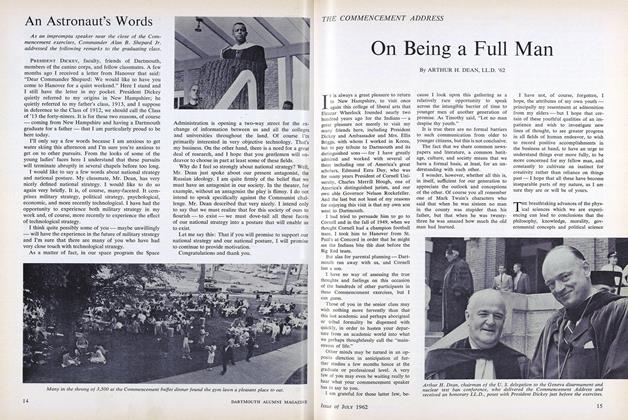

FeatureAn Astronaut's Words

July 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPONG PADDLES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureDisengagement

APRIL 1991 By John Sloan Dickey '29 -

Feature

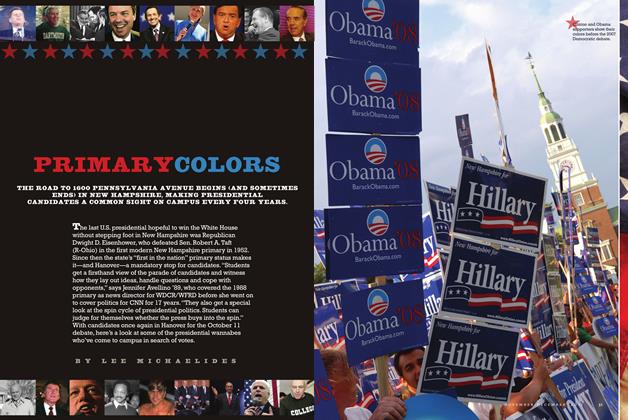

FeaturePrimary Colors

Nov/Dec 2011 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

FEATURES

FEATURESCapital Business

MAY | JUNE 2021 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69