Although they may not have been admitted as undergraduates until 1972,women have been a part of Dartmouth history from the beginning

Although 1972 was the first year in which undergraduate women were enrolled as candidates for the Dartmouth degree, the history of the College has not been without its "feminine presence."

The feminine part of the Dartmouth story goes back, in fact, to the College's pre-history. The Indian Charity School conducted by Eleazar Wheelock in Lebanon, Conn., before he moved his educational endeavors to Hanover, had enrolled both Indian boys and girls.

It appears that Dr. Wheelock's early school was coeducational for reasons other than concern for the education of women. In a letter to Sir William Johnson in 1761, Wheelock applied for six Indian children, specifically asking that two be girls "since they could be more cheaply supported and the allowance was too small to cover the expense of six boys." Actually, in the year previous, provision had been made for five Indian girls, but whether they ever enrolled as students is not known.

In a letter from Wheelock to a friend, also in 1761, he reported on the progress of one of the Indian girls at the school, saying "she has some proficiency in learning since she came last spring ... she then hardly knew her letters (and indeed is more backward in reading than in other parts of her learning)."

The minister-turned-schoolmaster in another letter made reference to Indian girls who were students at the school, mentioning that he "hoped their education would not be very expensive."

By December of 1762, some 25 charity scholars were enrolled, four of them girls who attended the school one day a week and lived with neighboring families to learn housekeeping. The school itself was held in the meetinghouse, and although the boys had for their use a pew in the gallery over the west stairs, the parish "voted to allow Mr. Wheelock's Indian girls liberty to sit in the hind seat on the women's side below."

An interesting letter from Mary Secuter, a Narraganset Indian who entered the school in 1763, related her need to confess to Wheelock that she had sinned, become drunk, and behaved in a "leud, immodest manner among the school boys," and on another occasion she made a similar confession that she felt wicked and sinful, apparently succumbing to intoxication again. This second letter, written five years after her admittance to the school, indicated that she felt she deserved to be dismissed, but that she strongly desired to stay. A final letter, a few months later, affirmed "... my faults have been overlooked with tenderness when they have deserved severity. I am quite discouraged with myself. Ye longer I stay in Ye school. Ye worse I am — don't think I shall ever do any good to Ye cause and it will cost a great deal to keep me here, when will be spending money to no purpose. ... I shall be glad to leave the school next week and be no longer a member of it."

The decision in the late 1760's to use solely "English Blood" to civilize the Indians necessitated a fresh start and moving the school into the wilderness. Governor Wentworth of New Hampshire had long been a supporter of the school and promised six square miles of land on the Connecticut River as an endowment for the new institution. Wheelock set about the framing of a charter and requested that the word "College" be used instead of academy.

On December 13, 1769, the Charter of Dartmouth College was signed and sealed. Those to be educated were, in the words of the charter, "Indian youths," "children," and "students." Nowhere to be found is a statement restricting education to males. This lack of direct reference to the sex of prospective students is hardly surprising. The times dictated the mores. Formal education of any kind in the 18th century was for males only. When Leon Burr Richardson wrote in his History of Danmouth College nearly 150 years later that he found the charter to be the most liberal of any college in the country, he was not assessing it with a 20th century social conscience.

Thus the school moved to its New Hampshire home and shifted its emphasis to the education of more English youths. But the enrollment of women was not to be, although the Charity School continued to include some Indian girls. With increasing frequency, the letters and papers of the College made reference to "boys," "sons," or "young gentlemen." It was apparent that Dartmouth College (as a separate entity from Moor's Charity School) had no intention of admitting women — Indian or white.

The Indian Charity School in Connecticut enrolled 16 girls from 1761 to 1768, the last recorded date of attendance of an Indian girl at the school, but there is some evidence that females attended the Hanover school for some years after this. Dr. Jeremy Belknap, sent by New Hampshire Governor Wentworth to the 1774 Commencement, described the colorful ceremony in the following way: "The Connecticut lads and lasses, I observed, walked hand in hand in procession, as 'tis said they go to a wedding."

Judah Dana, Dartmouth Class of 1795, who was invited in his junior year to assist in teaching at the Charity School, revealed in his diary that women were still enrolled. He wrote, "We had a numerous school of about 70 scholars, among whom there were not less than 20 young ladies."

In a later reference to women at the Charity School, a local newspaper account described exercises by the members of the Academy: "The procession of the pupils from the Academy to the Chapel, consisting of about eighty of both sexes ... was brilliant and pleasing."

But Dartmouth College, the senior institution, was not enrolling female students. None sought admittance or sent inquiry about the possibility of attending. The College at this time was conforming to the expectations of the day; higher education for women was simply not a matter for concern.

An interesting portrayal of Dartmouth in the early 1800's comes from Sarah Connel who described a College commencement in her diary. She and her father drove from Concord, N.H., to Hanover for the 1809 event, at the invitation of a friend who had graduated in 1807. In general, she found the countless orations and teas rather dull, but she did enjoy dancing until the early hours of the morning at two balls with many boys whose names she could not remember.

Colleges were originally established to educate the clergy and somewhat later to prepare their students for the professions. All the professions of the day were, of course, almost exclusively maledominated. As colleges multiplied, however, their objectives broadened and the reasons for excluding women began to blur, since women as well as men were concerned with theology and teaching.

During the 1800's, the education of young women was not being ignored in Hanover, where several girls' schools had been established. They were not institutions .of higher education (indeed, they barely provided secondary school equivalency) but in a limited way they served a useful purpose, and certainly lent some color and interest to the town and to Dartmouth College.

Peabody Boarding School for girls was founded in 1840, and by 1864 three more girls' schools had been opened, although the length of time they actually remained in business is uncertain. Rood, Sanborn, and Hubbard were all female boarding schools, the latter run by Professor and Mrs. Hubbard who continued it until about 1868. It has been noted that several of the girls who attended these schools later married and had sons who became Dartmouth men.

Regulations at the schools were very strict, and according to an observer at the time: "One of the curious things of the Peabody School days was the mandate that the young women should not step upon or across the college campus, and the rule was properly carried out by the girls."

Miss Julie Sherman kept a girls' school in Hanover before the Civil War and the sight of her girls marching across the green to the town bath house was a great source of levity ,among Dartmouth students. Susan Coolidge, a student at Miss Peabody's, wrote a children's book about her experiences which were only thinly disguised as fiction. In describing the girls' weekly trek to the bath house, she wrote: "We go across the green and down by Professor Seecomb's and we are in plain sight from the college all the way, and of course those abominable boys sit there with spy glasses and stare as hard as ever they can. It's perfectly horrid."

Apparently, Hanover girls were greatly admired, especially if they were attractive and were "picked off by youths as soon as might well be. But not enough of them were available to make much impression; and the students in general were compelled to restrict their opportunities for feminine society to periods when they were away from home. On the other hand masculine companionship . . . was abundant and well organized."

J. Whitney Barstow, Class of 1847, gives us an interesting glimpse about the feminine company of Dartmouth students when he speaks of serenading expeditions which were held two or three times a week, accompanied by guitar and an occasional flute. He recalled that there was a great deal of labor involved in the rehearsing and traveling (they had to be back for morning chapel), but it seems to have been a pleasure well worth the while "... not only in Hanover (when not interrupted by a few silly members of the faculty), but in Lebanon, Norwich, and White River Junction where most of us had young lady friends."

In 1872 two committees were appointed by the Trustees, one to study military instruction and the other to study coeduca- tion. The coeducation committee was composed of President Smith and Messrs. Spalding and Quint. The issue was raised in response to the fact that the University of Vermont had begun to admit women in 1871, and the discussion of higher education for women was general at the time. However, in New England particularly the movement for educating women seemed to be taking a turn in the direction of separate colleges, and the Dartmouth committee never reported back.

Additional pranks on the part of Dartmouth students in regard to another "female academy" were in evidence about this time. The Dartmouth in 1878 printed a notice reading: "Students visiting West Lebanon will please take notice that Professor Hiram Orcutt has been appointed special policeman and henceforth all persons caught trespassing on the grounds of Tilden-Female Seminary will be seized and held trial by that officer."

A year later, a stand against coeducation (probably the first taken by the local press) appeared in The D and was undoubtedly the opinion of the editor, although no by-line appeared: "... most people of sense appear to be well satisfied that there is a propriety in not herding young men and women together in our great public institutions of learning."

The period from 1894 to 1917 is of special interest and significance to Dartmouth because it was during those years that the first female graduate students gained admittance and earned graduate degrees. A year before the first two women were accepted at the College, The Dartmouth, as if in anticipation of the event, printed the following commentary: "The charter at this institution states that Dartmouth was founded for the education and instruction of the youth of the land. We can have coeducation. Do we want it in Dartmouth? ... at Dartmouth, coeducation would never succeed. Hanover is too far removed from a center of trade and activity to attract young ladies, and further- more, its accommodations are inadequate. New and expensive dormitories and recitation halls would have to be built. ... In Colleges where coeducation has been tried, it has proved a failure, and that is enough to condemn the scheme ... Coeducational colleges which were once strong as schools for men are fast losing their prestige. Dartmouth cannot afford to. Co-ordination and arrangement after the style of Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges, we would welcome here, but coeducation never."

This warning was soon a reality with the acceptance of Katherine Quint and Anna Hazen, close friends, teachers of biology, and both desirous of graduate study in their field. They were perhaps helped by the fact that Miss Quint's father. Rev. Alonzo Hall Quint, was a member of the Class of 1846 and a senior member of the Board of Trustees of the College.

On remembering the details of her admittance years later, Miss Quint felt that President Tucker personally was in favor of accepting her for graduate study in biology, but that he required confirmation from the Board of Trustees. "When my father ... heard of my application, he was as surprised as the others and refused to vote on the question."

A year earlier, in 1894, the Legal Committee of the Trustees had been requested by the faculty to interpret the words "English youths and others" which appeared in the Charter's definition of those to be admitted to Dartmouth. The Committee returned a verdict in favor of women, interpreting the words to mean "youths of all nations and both sexes, and stating it as a question of power merely, it is our opinion that the corporation has the power to confer degrees upon females and to admit them to the advantages of the College."

In 1895 The Dartmouth ran an editorial explaining the enrollment of these women and reassured their readers that coeducation of undergraduate women would certainly not accompany this act of deviation: "The admission of ladies to post-graduate courses in Dartmouth is a new move for Dartmouth, but it is safe to say, for the sake of quieting the uneasiness, that no harm will come from it. Some point to the fact that coeducation in Wesleyan began by admitting ladies to the post-graduate courses. Whether this is true or false is not at the present ascertained. Yale now admits ladies to the post-graduate courses, but she does not intend to introduce coeducation, more than Dartmouth does. Those in authority have made the guarantee that coeducation in Dartmouth is a thing of imagination and not a possible reality."

Miss Quint's master's degree in biology was granted in 1896, and she thus had the distinction of being the first woman to receive a Dartmouth degree. She was made an honorary member of her father's class (1846) and attended class reunions and alumni club meetings until her death.

A year after Katherine Quint received her degree, her friend Anna Hazen earned an M.S. in biology and she too was later made an honorary member of a class (1907).

Henry K. Urion, Class of 1912, recalled with well-contained enthusiasm, the first Dartmouth summer terms to which women were admitted. He reported that he had attended a session during July-August 1910, owing to the fact that he had failed a course in his sophomore year. In describing the women, he said: "They were better left uncharacterized but they were something! ... I am all for the addition to the curriculum of a summer quarter; however, recalling the female collection that attended Dartmouth's summer session of yore, I advise the boys not to become too excited about the inauguration of Dartmouth coeducation."

This portrayal drew criticism from another alumnus, who sent the AlumniMagazine a picture of the female summer students in the 1913 session, commenting on how attractive they were.

In 1915, persistent rumor had it that a benefactor of the College had offered money to build several new dormitories if the Trustees would vote to allow women to become undergraduate degree candidates. College authoritories neither confirmed nor denied the rumor, but it was pointed out by one of them that nothing in the Charter prevented women from receiving degrees at Dartmouth, and as a matter of record, several women had received masters' degrees. A Dartmouth editorial responding to the rumor, philosophized that "... those of an aesthetic turn of mind can picture the impotent wrath of prominent Boston alumni when the pink teas deepen to crimson and high collars and engagement rings encircle respectively the necks and hands of those who erstwhile ruled the sodden and bloody football field, attired in nasty, muddy sweaters, and scarred football pants, now to be discarded for the society trouser."

The absence of girls was distressing to some, but it was viewed as an asset by many others. The Class of 1926, for example, listed among 1700 reasons for choosing Dartmouth the following: "Hanover, a place where no girls are close at hand. The same class also listed as one of its favorite sports and recreation, "thinking about girls."

In the same year, the custom of spending weekends out of town became widespread. Considering that only 39 students had permission to drive automobiles in Hanover, that roads were extremely poor, and that the train provided only restricted travel to uncertain destinations, this seems a remarkable activity! According to The Dartmouth, at least one explanation for "weekending" was that the morale and vitality of the student body had never been lower, but the reasons for this malaise were not specified.

Winter Carnival was one of the two occasions during the year when girls were present on campus in large numbers, the other being Commencement. At both of these affairs, the women were heavily chaperoned. Describing the 1930 Carnival, the Alumni Magazine waxed eloquent that "Girls, girls, girls-lovely sweethearts, gay flirtatious maidens, Vassar girls, Smith girls, just girls, most of them beautiful, took possession of the town." Of this assemblage, 462 stayed in fraternities, the others at the Hanover Inn.

Anticipation of that Winter Carnival prompted undergraduate Albert I. Dickerson to write: "As the about-to-be host goes to the train Thursday noon to meet his Carnival guest, he feels like the boy who is about to reach the top of a Coney Island roller coaster. It is too late to turn back now, you have to take a deep breath and plunge in. And one hardly knows whether to sit tight and hold on hard or to stand up and yell Whoopee. Instead, one runs up and collects a smile, a greeting, an armful of baggage, and Carnival begins. Of course there is always the question "Will she kiss you or not?' We never stayed around to gather statistics but the average seems discouragingly low."

In 1932, J. R. Willard, Class of 1867, became one of the first alumni to publicly urge coeducation for Dartmouth. In a letter to the Alumni Magazine Willard expressed great praise for Vassar College, finding it remarkable that a women's college was able to give its students practical instruction in such disciplines as Astronomy with the aid of an excellent astronomical observatory "equal if not superior to the one Dartmouth possesses." He went on to surmise that "... the day is not far distant when our own alma mater shall welcome to her halls the fair daughters of Eve, and sweet girl graduates with their golden hair shall grace the Bema on commencement day. Meantime, let us thank God and Matthew Vassar that the dry bones of reformation have at last left their century-beaten tracks." There was no overt reaction, either pro or con, to Willard's letter.

But if Dartmouth was seemingly taking no heed of Willard's words, her daughters nonetheless were organizing support for the College. By 1930 Dartmouth wives, mothers, and daughters in the Boston area had formed the Dartmouth Women's Club of Greater Boston "to promote acquaintanceship among Dartmouth women, to show our loyalty to the College, and to establish a scholarship loan fund for the benefit of Dartmouth students." "To Dartmouth wives long concerned that women do not marry other men through choice, but only because there are not enough Dartmouth men to go around; to Dartmouth daughters who were grown before they learned that there are other colleges, and to Dartmouth mothers who had sent a teenage boy off to college and have him become unmistakably a Dartmouth man, it was a natural association."

In the spring of 1935 the Social Study Committee at the College undertook a study of the phenomenon of the Dartmouth weekend and ways by which Hanover could be made more attractive to the undergraduates. Apparently Saturday and Sunday still saw the exodus of large numbers of students for off-campus parties, dances, and dates. Keeping the students in town on weekends seemed to be a principal goal of the committee, which realized that the attractiveness of Hanover to the students was directly related to the presence or absence of young women, and that mixed social functions of some sort needed to be arranged. In spite of this revelation, the Class of 1936, in its senior balloting, voted by a wide margin that Dartmouth should not become coeducational, while fully half the class stated they intended to marry before the age of 30.

A tongue-in-cheek article in The Dartmouth in 1937 said "our plan would be for Dartmouth and Smith (or Wellesley), take your pick, to unite. We'd split our campus and their campus in half - establish male and female sides to the barriers. The Masses and the Giles could be boys' dorms, Fayers, New Hamp and Topliff — female. Tuck School could stay by itself." The article fancied a general reunion of the entire school at Carnival time prophesying that the plan would solve the "Hanover sex situation and that it would probably take care of Smith and Wellesley in the bargain."

In 1938, Amelia Peters, an Indian girl from the Wampanoag tribe attempted to enter the College. Her father, having read that all full-blooded Indians could enroll tuition-free, planned to ask College authorities to allow his daughter to be admitted. Amelia apparently did come to Hanover, but whether or not she actually submitted an application is unclear. If her attempt at enrollment was made, it was not successful.

Dartmouth, during the Second World War, was a somber place. Carnival became less of a spectacle and was eventually eliminated altogether to await the return of brighter days. The College concentrated its energies on the war effort, and became temporarily a naval training institution.

The women of Dartmouth, during this period, took over an active role in the affairs of the institution, assuming jobs formerly done by men. Dartmouth wives, mothers, and daughters handled a variety of College activities by typing notes, mailing postcards, acting as class agents, and gathering information about class members. Some faculty wives even helped with teaching, acting as volunteers in their husbands' courses. They were all warmly applauded by the College which expressed its gratitude and called them "damned good Dartmouth men."

With the return to campus of more than 150 married veterans in 1945, Middle and South Fayerweather dormitories were converted to married student quarters to alleviate a severe housing shortage. The presence of so many student wives suddenly created a distinctly feminine atmosphere in the town — "pretty girls can be seen in the middle of the week" enthused one student.

The appearance of so many older married students on campus prompted TheDartmouth to lament, "What chance will a poor bachelor have of making an A in a course when the married men can invite a professor over to the house for a real home cooked dinner?"

Other problems beyond the mere logistics of housing arose from the sudden influx of the married students and their wives. Most of the women wanted to work, but there was a scarcity of available jobs in Hanover. There was also the question of what they would do for recreation although some suggested that "the recreation problem will probably take care of itself with the start of knitting circles, sewing bees, dances, or whatever women do when they get together." Most of these problems were solved in time and the married students formed a close-knitgroup which became socially very active

One setback for the wives resulted from a College ruling that they would not be allowed to attend regular Dartmouth classes. However, sympathetic faculty members arranged a series of informal leetures and classes specifically for these women.

Because women (wives of students and secretaries) were denied permission to attend classes, they invited professors to give lectures in their homes. Prof. John Hurd of the English Department prepared a comprehensive reading list, and other faculty members who specialized in the assigned authors were asked to speak. In general, the scheme seemed to work and the women were satisfied that they were receiving at least some kind of a Dartmouth education.

Coeducation became a viable issue in 1960 because of two simultaneous events. On January 6, President Dickey announced at a press luncheon at the Dartmouth Club of New York that Dartmouth would probably initiate a summer term in 1961, and that undergraduate women would be admitted to it. On the very same day, The Dartmouth published the first of a four-part series reporting on a panel discussion about coeducation which had occurred a few months earlier. The members of this panel were Dean Fred Berthold of the Tucker Foundation, Dean of Freshmen Albert Dickerson, Dean of the College Thaddeus Seymour, Prof. John Stewart of the English Department, three undergeraduates, and one student wife.

Both of these events emphasized the fact that women would be admitted only for the Summer Term and that they would not be considered full-time degree candidates at Dartmouth College. Nevertheless, many saw this as an omen and the student body embarked on a lengthy debate as to the implications of the proposal.

The discussion which was reported in The Dartmouth appears to have been the first serious one of its kind. It was free of either hostility or romantically inflated vignettes of Dartmouth life.

In the first day's report, Professor Stewart, a proponent of coeducation, cited the feminine point of view as an element then missing from all aspects of the College. He felt that men and women needed to "respect each other as adult human beings," and this was unlikely to happen at a monosexual school.

Dean Dickerson, representing the anticoeducationists, suggested that students would be inhibited and embarrassed in coed classes. Student wife Judy Kohn agreed, believing that Dartmouth students would not speak out or ask questions if classes were mixed.

Mark Hinshaw, an undergraduate, further elaborated on the theme that females would be distracting and that schoolwork would be neglected.

The second day's report continued with Dean Berthold's assertion that the presence of women at Dartmouth would be a "civilizing influence." Dean Dickerson countered this argument by stating that he believed Dartmouth males would remain uncivilized whether or not women were on the campus, and that they "will still go without shoes and hardly any pants." But he mentioned that his greatest objection would be the loss of Dartmouth fellowship.

"What is it that we now have about a men's college that is worth protecting?" retorted Dean Berthold in the third installment of the series. Answering this query were Dean Seymour and Mark Hinshaw with impassioned exhortations on the importance of Dartmouth friendships. The fear of losing some part of the spirit which Dartmouth men have held for generations was reaffirmed time and time again.

All the participants agreed that it was a valuable experience for men to develop close friendships, but Professor Stewart argued that strong male friendships were not necessarily peculiar to all-male schools, that men could create the same patterns of friendship at coeducational schools. He also emphasized that non-romantic friendships with girls were possible at coed schools but unlikely at monosexual institutions. Speaking from his own experience as an undergraduate at a coed school, he stated, "I learned how to be a friend of a woman without thinking of her always in erotic terms, and this has been an exceedingly valuable lesson in life."

The final report on the series included a remarkable statement by Dean Seymour who said, "As soon as the College becomes responsible for the welfare of girls, we need to set up in the neighborhood certain controls. ... It certainly would be unthinkable to permit girls in the dormitories, and be unthinkable for girls to drink. At least at North Carolina, it was the case that girls could not be in the presence of a male student who was drinking."

This ended the panel discussion. But as might be expected, a Pandora's box of thoughts, attitudes, feelings, and ideas was opened on the subject by students and faculty. Advocates and opponents of coeducation deluged the paper with letters each supporting their "side." Sociology Professor Louis Schneider hypothesized that many students and alumni were opposed to coeducation for three major reasons. First on grounds of distraction, that the "essential business of studying would not get done." Secondly, the "desire to maintain for some years a situation where full responsibility need not be taken," intimating that the mere presence of women on campus foreshadowed a future life of domestic responsibilities. And finally that an all-male situation allowed for a comfortable and casual existence which included rough language and manners, and general informality.

Thus coeducation became a major issue in 1960. Almost every member of the College community had a firm idea of where he or she stood on the issue; few were neutral. But it was to be another twelve long years before the Trustees of Dartmouth College would vote to allow women to enroll as undergraduate degree candidates.

Summer school students, 1914, portraying Greek maidens in the Bema.

Katharine M. Quint, A.M.'96, was thefirst woman to receive an earned degreefrom Dartmouth. An 1890 graduate ofWellesley, she wanted to follow her fatherand two brothers to Dartmouth and brokeprecedent to do so. Much feted by thealumni, she was an honorary member oftwo classes, 1846 and 1896. She taughtclassics at Goucher College and threeschools and died in 1956 at the age of 88.

THE AUTHOR: Joanna Sternick, Hanover resident, earned her bachelor's degree at the University of Vermont, her master's degree at Dartmouth, and is a doctoral student at the Higher Education Center of the University of Massachusetts/Amherst. Her research is concerned primarily with women in higher education and she is currently teaching a course on the history of women and the law at the University of Massachusetts. A former reporter for Dartmouth Station WDCR, she hosts a weekly news-interview show on WRLH-TV, Lebanon.

This "Fête Champêtre," or rural frolic, took place in the summer of 1915.

The gymnastics of a modern-day coed area far cry from the ladylike dances of thesummer school women of fifty years ago.

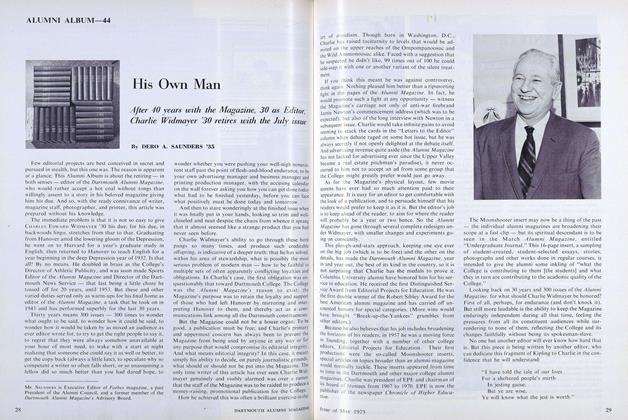

World War II veterans, back on campus with wives, occupied the Fayerweathers, wherethe signs of domesticity gave the Dartmouth campus a startling new look.

One of the couples then living in SouthFayerweather was Air Force Major RobRoy Carruthers '42 and his wife Mary.

A bygone ritual — down to The Junctionto see one's date off on the B & M.

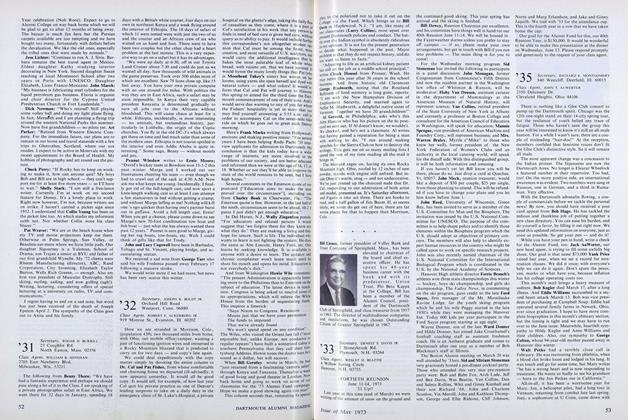

Some of the history-making coeds of 1972, relaxing on the dock while awaiting their turnto practice on the Connecticut as members of the women's crew.

Joanna Sternick is continuing herresearch on the role of women in Dartmouth history, and has it in mind to writeanother article that will cover the storyfrom 1960 up to the present time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

May 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75 -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

May 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Yell Revisited

May 1973 By Russell O. Ayers '29 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleHis Own Man

May 1973 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

May 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, JOHN T. AUWERTER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

DECEMBER 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

FEATURE

FEATUREThey Are What They Eat

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By JESSICA FEDIN ’17 -

Feature

FeatureDrive

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Richard Durrance'65 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

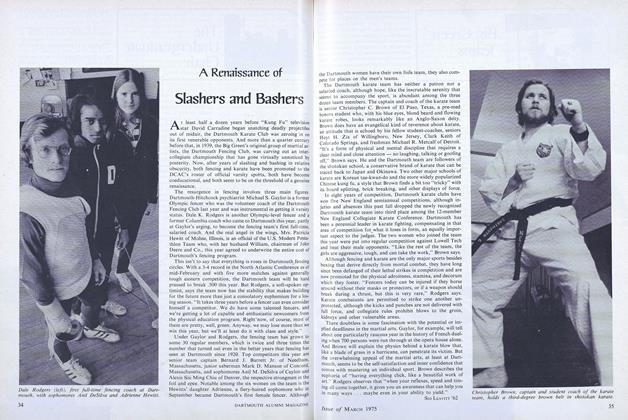

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62