In the April 30 issue of The Bulletin, sent to all alumni, President Kemeny wrote about the report of the Task Force on Budget Priorities. The opening section of the report, entitled "Goals and Purposes," is of general interest and has been especially well received. It was written by Louis Morton, Daniel Webster Professor and Chairman of the History Department. With his permission and that of the task force chairman, Dean John W. Hennessey Jr. of Tuck School, it is printed here.

A. Introduction

The Task Force on Budget Priorities was established by President Kemeny for the purpose of reviewing the five-year projection of income and expenditures of the College and to recommend to him how best to meet the guidelines laid down by the Board of Trustees without compromising the equality of education at Dartmouth. Since this charge involves judgments as to the relative importance of the various areas of the College, the Task Force recognized that it would be necessary first to establish criteria against which to measure the relative importance of a great number of competing activities. These criteria, it believes, can only best be derived from an analysis of the purpose and goals of Dartmouth College now and during the next decade.

But we cannot consider Dartmouth College in isolation. The College is part of a large and complex system of higher education that affects all that it does and shapes not only its purpose but also its relationship to the larger community and to the goals of a democratic society. Our starting point therefore must be the nature and purpose of higher education, and especially of the liberal arts, in the United States today. Purpose is prelude, the prerequisite to policy and program. For whom is a liberal education designed? What is its content? And what are the intended roles of the educated in society? The answer to these questions viewed in the longer perspective of history may help us not only to establish criteria for settling priorities in the years ahead but also to arrive at a better understanding of the purposes of the College.

B. Perspective: An Historical Hop,Skip and Jump

Much has been written about the purposes of higher education and of the liberal arts. It is a subject about which there has often been disagreement and one that has been debated since the days of ancient Greece. As early as the 4th Century B.C., Aristotle, commenting on the purposes of higher education, wrote: "The existing practice is perplexing; no one knows on what principle we should proceed - should the useful in life, or should virtue, or should the higher knowledge be the aim ..." Nor was there any agreement in his time on the means by which any one or all of these aims could be achieved. These differences have never been entirely resolved, but on one proposition most would agree: A liberal arts educationhas meaning and vitality only when it isrelated to and grows out of the needs of thesociety that supports it. When it ceases to reflect the society or when it seeks to preserve culturally outmoded forms or practices then it becomes arid and lifeless. It is safe to conclude, therefore, that the purpose of a liberal arts education will be different in different times and places.

Higher education in America, like so many other American institutions, is derived from 16th and 17th Century England and Western Europe. In the colonial period it was based on the British aristocratic concept of the gentleman and was intended for the son of the well-born and wealthy, to prepare him to take his rightful place as a leader of society. It was limited therefore to the members of a select group whose status exempted them from manual labor and menial tasks. The purpose of such education, S. E. Morison noted in his History of HarvardCollege, was "to furnish the State with competent rulers, the Church with a learned clergy, and society with cultured men." For two centuries, this idea governed higher education; determined who should receive this education and the nature of the curriculum. Children would be taught the three R's, to read the Bible "that they might know God's truth," to write, and to "cipher" so that they might lead an "honest life"; older boys would be selected for instruction in the "learned languages" so that they might study the world's best thought and literature. From these would be selected the few who would go on to a college for university training.

By the 20th Century, the growth of knowledge and public education had revolutionized the nature and content of a liberal arts education. We need not pause here to describe how the revolution came about. To do so would require a study of political and social developments in the 19th Century, the effect of German thought on American education, and a number of other matters. But by the first decade of the 20th Century, the student body of American colleges and the newly created universities had expanded enormously and its character changed radically to include students from all levels of society and from both sexes. The content of a liberal arts education changed also, so much so as to result in virtually a different kind of institution. And in place of a compact curriculum devoid of elective studies and focused on the aims of a small governing class the curriculum grew until it offered almost an unlimited variety of courses. Colleges and universities today serve men and women from a wide range of social positions whose goals differ widely and whose needs therefore as expressed in the content of the liberal education, include instruction in subjects far removed from that of an earlier day.

C. The Goals of a Liberal Education:General

There are a number of ways of defining the nature of a liberal arts education. President Kemeny found the answer in five basic propositions or premises. Others have identified different or additional elements of a liberal arts education. It seems to us that, from the point of view of the needs of society as well as the individual, the liberal arts college must have three essential goals if it is to achieve its purpose. First, it must provide,in President Kemeny's words, "an overviewof the breadth of human knowledge and activity" and an understanding of "theproblems threatening our civilization."

American society requires men and women who are fully informed and able to cope with a world that is highly complex, technologically oriented, and under challenge from all directions. In such a society, a liberal arts education should be designed to provide a broad knowledge of the major areas of learning: the natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the fine arts. Not everyone who receives the A.B. degree, however distinguished his record, can be considered liberally educated. Certainly one who does not have some basic understanding of the natural sciences can hardly be considered an educated person. And the same must be said for one who has little or no knowledge of English literature, history, philosophy, or economics.

Since a liberal education is designed to prepare the student to think and act effectively in later life, one who does not possess a broad knowledge - breadth need not be synonymous with superficiality - is illequipped to do so. But it should be said that the possession of knowledge does not necessarily imply intellectual competence. The end of a liberal education may not be the acquisition of knowledge, but certainly knowledge is, in Cardinal Newman's words, the indispensable condition of expansion of the mind and the instrument of attaining to it."

The older goal of a liberal arts education, to provide leadership, is not by any means obsolete. But the nature of that leadership and the social origins of the leaders have changed. Today the professionals, lawyers, managers, scientists, engineers, doctors, etc.

- i.e., the products of our professional schools - provide the leadership. But leadership in this sense does not necessarily mean governing but, as Ortega defined it, the power to exert "a diffused pressure or influence upon a body politic." It is of the firstimportance to society, therefore, that thosewho receive professional training, because oftheir influence upon the society, should havea broad knowledge and be steeped in theculture of the age, and this is another reason why "an overview of the breadth of human knowledge" should be one of the first goals of a liberal arts education.

A second goal of a liberal educationshould be the cultivation of those skills andreasoning abilities that enable us to thinklogically and clearly and to organize andorder our thoughts in logical sequence. To achieve this goal the student must experience the intellectual processes of the several disciplines, be aware of how to assemble and organize the data, how to reason to a conclusion. The methods of each of the areas of knowledge contribute to this end. But intellectual competence involves more than method; it involves also an understanding of what men have thought in the past, what men have felt, and the sources of men's action.

Finally, a liberal education should be concerned with attitudes, ideals, and traits ofpersonality and character. Though these qualities are hard to describe and difficult to measure, they are nevertheless the hallmarks of the cultured man and woman and should be a goal of liberal education. The intolerant, the unwise, and the intellectually stagnant, no matter how well-informed or capable of reasoning, can not really be considered a liberally educated person. Such a person should be balanced and mature in his judgments, temperate and tolerant of different points of view, and not subject to the fear of new ideas or to social and racial prejudice. Moreover, he should have a purpose and a philosophy of life to give him stability and intellectual curiosity to push forward the frontiers of knowledge.

Central to these three goals of a liberal arts education is the work of the mind, the development of intellectual competence. This involves two groups: teachers and students - the essential ingredients of a liberal arts college or any institution of learning. Without both of these there is no education. A college without a faculty is not a college at all but a band of young people, and one without students may be a research center or any number of other things but it is not an educational institution. And with these two, there must be the resources required for teaching and learning - library, laboratory, computer, classrooms, adequate working conditions for faculty and living conditions for the students. These are central to a college or university, the basic ingredients of higher education. No other institution in our society possesses these elements and no other institution can do what it can - produce a liberally educatedcitizen. This is the prime business of higherlearning; it is the one thing a college or university does that no other institution in our society can do - give to every student an acquaintance with the varieties of learning and knowledge that a modern man needs .

The broader needs of society and a concern for the welfare of all men, i.e. the universal rather than the individual or particular, are also a part of a liberal education. The particular has to do with the advancement of one's personal fulfillment, a recognition of the full potential of each man and woman. But each person should have also a concern for the well-being of all men and if this is one of the characteristics of an educated man then it must also be a characteristic of the educational institution. A college therefore embraces the goals ofthe society in which it exists as well as thegoals of each individual. The college should then have an institutional purpose that reaches beyond the education of the individual and his private interests.

D. Dartmouth College: Goals and Purposes

Dartmouth College shares the purposes and goals of all liberal arts colleges and institutions of higher learning in the United States. But every college and university, like every man, has a character and quality of its own, and Dartmouth College is in many ways distinctive and unique. The recommendations of the Task Force and its ordering of priorities must therefore take into account not only the goals Dartmouth shares with other colleges and universities but also the qualities that make it different and give it its special quality. First among these is theprimacy of undergraduate education and theliberal arts, what an earlier president of Dartmouth called the liberating arts in the sense that it is the task of the College to free as well as to nourish men's minds. Undergraduate education in the liberal arts was the main concern of the College at the start and its exclusive preoccupation during the 19th and through the first half of the 20th Century. And though it is no longer an exclusive concern, it is still a distinctive feature of the College and the quality that sets it off in some measure from the more complex universities of 20th Century America.

This emphasis on undergraduate education and the liberal arts does not diminish the importance of preprofessional and professional training, of research and of graduate education - the hallmark of the modern university. Nor does it mean that Dartmouth is not concerned with professional and graduate work. Over the years, Dartmouth has offered a variety of degrees in addition to the A.B., and has added professional schools, first in medicine, then in engineering, and finally in business administration. And most recently, the College has added graduate work leading to the Ph.D. degree in about a half-dozen fields. In size and the variety of its offerings Dartmouth has the characteristics of a small selective university, yet it retains the name of a college (for historic reasons) and its emphasis on undergraduate work. Characteristically, it evaluates its variousprofessional and post-graduate programs inpart in terms of their contribution to theliberal arts and undergraduate education.Undergraduate education at Dartmouth isviewed essentially as an end in itself ratherthan as a preparation for graduate work. In a sense this emphasis has been one of the major achievements of the College and accounts in part for the richness and variety of its liberal arts program and the excellence of its faculty.

Dartmouth's preeminence in the liberal arts has also had an effect on its professional and graduate programs. One of the requirements for admission to graduate work at Dartmouth is the completion of a liberal arts program that is the equivalent of a Dartmouth undergraduate program. This requirement is a recognition of the importance of a broad education in the liberal arts for the professional man in society today and this gives to a post-baccalaureate degree from Dartmouth a special meaning. The inauguration by President Kemeny of a liberal arts program for successful business and professional men entering into the highest levels of leadership in the corporate world is also a recognition of Dartmouth's commitment to the liberal arts.

A second feature of Dartmouth's specialquality is the sense of community it inculcates in its sons and now its daughters, a sense of being an integral part of the College and sharing in its goals and aspirations. This community, the Dartmouth community, is not limited to students and faculty; it includes also those who have passed through the College, those who are part of her past. How great an influence Dartmouth has on her students can be judged by the loyalty of her alumni; no college or university has so devoted an alumni body. Without their support the College would be far poorer indeed, not only in the material sense but in the spiritual as well. Support of these activitiesthat further this sense of community and tiestudents and alumni to the College thereforehas a strong claim on the resources of theCollege.

Contributing to the distinctiveness of Dartmouth is the commitment to excellence in all that it does, its determination to be an absolutely first-rate institution of liberal learning. This excellence depends first and foremost on the quality of its faculty and student body. These are the basic reasons for Dartmouth's preeminence, not only as an undergraduate institution but on the graduate and professional level as well. On this foundation rests Dartmouth's prestige and reputation, its ability to attract outstanding teacher-scholars and to draw on the Dartmouth community for support. To recruit and retain a first-rate faculty the College must provide the facilities they require in their work: a library, a computer center, laboratories and all the other things needed for research and for teaching - above all the best student body that can be enlisted. Thus, the first levy on the resourcesof Dartmouth College is its faculty; that requirement yields to none other and admitsno compromise. "The quality of a first-rate faculty and student body is always unfinished business," President Dickey once said. This is the first priority of Dartmouth College.

An institution is more than the creation of man; it is also the product of time and place, of its origins, its physical setting, and its traditions. Perhaps more than any other American college, Dartmouth's quality and character stem from these influences. Founded in the northern wilderness where country and climate gave significance to the struggle for existence, and dedicated by its founder to a special mission, the College early developed a tradition of hardiness and sense of purpose that was fortified by the fight for independence that gave it an important place in the larger history of the nation. In these origins can be found Dartmouth's association with nature and the outdoor life (an essential part of the quality of the College) and with the changing needs of society. Every age has its own challenges and Dartmouth has always responded to these challenges, reaching out in its concern with the larger issues of the time. It is this sense of institutional purpose that has given us the Great Issues course, the Tucker Foundation, and the Equal Opportunity programs. And it is this concern that has sent Dartmouth graduates into the Peace Corps, VISTA, Jersey City, ABC, and other activities dedicated to the welfare of all men.

As distinctive as its setting is its size. Over 7,000 applicants for . admission, asked to specify their reasons for choosing Dartmouth, named all the things for which the College is justly famed - faculty, location, athletics, computers, etc. But a great number qualified their response with a reference to the size of the College, the fact that it was large enough to offer the advantages of a strong education yet small enough to retain "intimacy, cohesion and warmth."

Above all Dartmouth is an experience in living, a life style composed in varying parts of excellence in education, a unique physical setting, a long and honorable tradition, and a strong sense of community. While other schools become huge and impersonal Dartmouth should strive to retain and enhance the "intimacy, cohesion and warmth" it now possesses, for these intangibles may very well be the most tangible way in which Dartmouth can stand out among comparable institutions. Dartmouth's resources thereforeshould be directed toward fostering a dignified, varied and civilized life style for allmembers of the Dartmouth community.

Each year for all the years of his presidency John Dickey closed his Convocation address with the same words.

"As members of the College," he told his student audience, "you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

"First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

"Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

"Third, your business here is learning and that is up to you."

It is up to us to keep Dartmouth preeminent in all things.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

June 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FIRST COED YEAR

June 1973 By Bruce Kimball '73 and Andrew Newman '74 -

Feature

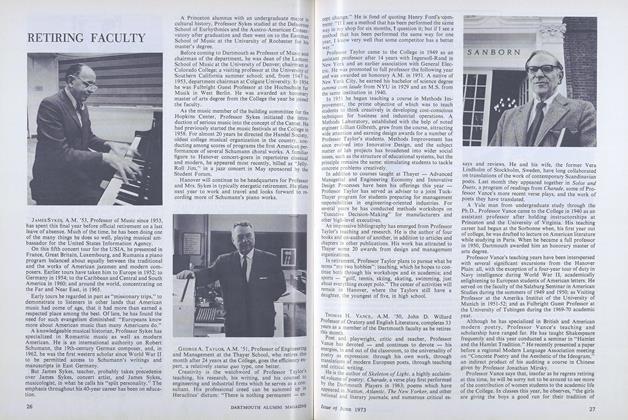

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureAvalanche Authority

June 1973 -

Feature

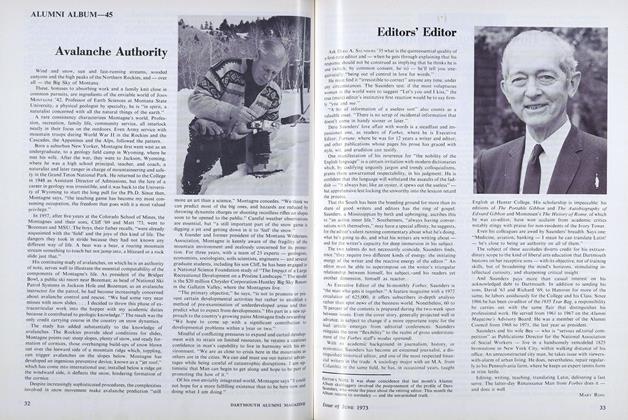

FeatureEditors' Editor

June 1973 By MARY ROSS

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

March, 1922 -

Article

ArticleAfternoon Session

December 1933 -

Article

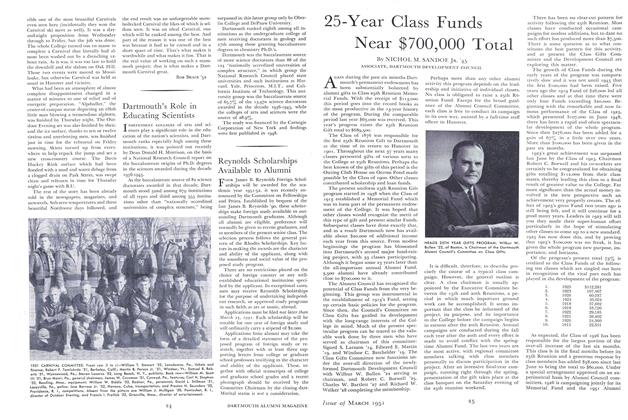

ArticleDartmouth's Role in Educating Scientists

March 1951 -

Article

Article1958 Football Schedule

January 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleGil Fernandez '33: a fine friend to the feathered

MAY 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22