Wind and snow, sun and fast-running streams, wooded canyons and the high peaks of the Northern Rockies, and - over all - the Big Sky of Montana.

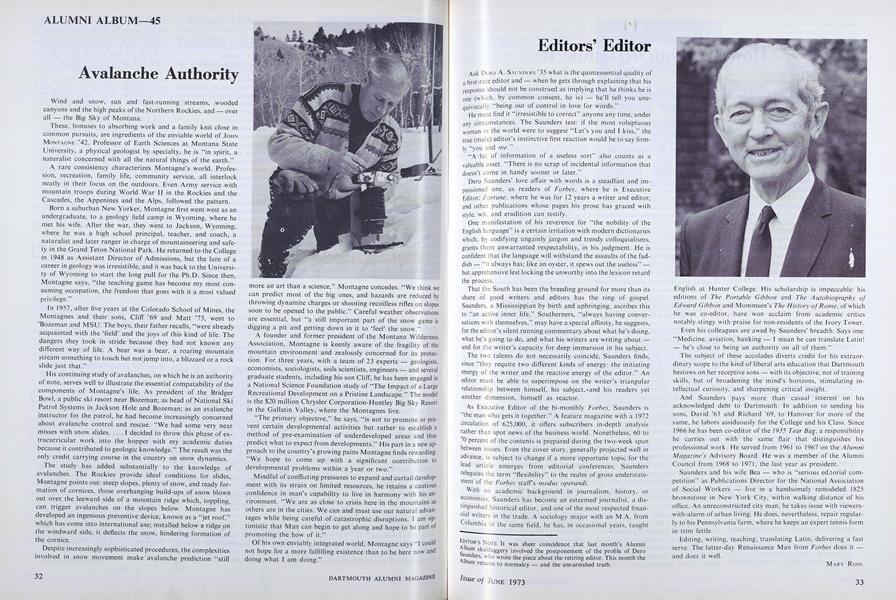

These, bonuses to absorbing work and a family knit close in common pursuits, are ingredients of the enviable world of JOHN MONTAGNE '42. Professor of Earth Sciences at Montana State University, a physical geologist by specialty, he is "in spirit, a naturalist concerned with all the natural things of the earth."

A rare consistency characterizes Montagne's world. Profession, recreation, family life, community service, all interlock neatly in their focus on the outdoors. Even Army service with mountain troops during World War II in the Rockies and the Cascades, the Appenines and the Alps, followed the pattern.

Born a suburban New Yorker, Montagne first went west as an undergraduate, to a geology field camp in Wyoming, where he met his wife. After the war, they went to Jackson, Wyoming, where he was a high school principal, teacher, and coach, a naturalist and later ranger in charge of mountaineering and safety in the Grand Teton National Park. He returned to the College in 1948 as Assistant Director of Admissions, but the lure of a career in geology was irresistible, and it was back to the University of Wyoming to start the long pull for the Ph.D. Since then, Montagne says, "the teaching game has become my most consuming occupation, the freedom that goes with it a most valued privilege."

In 1957, after five years at the Colorado School of Mines, the Montagnes and their sons, Cliff '69 and Matt '73, went to Bozeman and MSU. The boys, their father recalls, "were already acquainted with the 'field' and the joys of this kind of life. The dangers they took in stride because they had not known any different way of life. A bear was a bear, a roaring mountain stream something to touch but not jump into, a blizzard or a rock slide just that."

His continuing study of avalanches, on which he is an authority of note, serves well to illustrate the essential compatability of the components of Montagne's life. As president of the Bridger Bowl, a public ski resort near Bozeman; as head of National Ski Patrol Systems in Jackson Hole and Bozeman; as an avalanche instructor for the patrol, he had become increasingly concerned about avalanche control and rescue. "We had some very near misses with snow slides.... I decided to throw this phase of extracurricular work into the hopper with my academic duties because it contributed to geologic knowledge." The result was the only credit carrying course in the country on snow dynamics.

The study has added substantially to the knowledge of avalanches. The Rockies provide ideal conditions for slides, Montagne points out: steep slopes, plenty of snow, and ready formation of cornices, those overhanging build-ups of snow blown out over the leeward side of a mountain ridge which, toppling, can trigger avalanches on the slopes below. Montagne has developed an ingenious preventive device, known as a "jet roof," which has come into international use; installed below a ridge on the windward side, it deflects the snow, hindering formation of the cornice.

Despite increasingly sophisticated procedures, the complexities involved in snow movement make avalanche prediction "still more an art than a science," Montagne concedes. "We think we can predict most of the big ones, and hazards are reduced by throwing dynamite charges or shooting recoilless rifles on slopes soon to be opened to the public." Careful weather observations are essential, but "a still important part of the snow game is digging a pit and getting down in it to 'feel' the snow."

A founder and former president of the Montana Wilderness Association, Montagne is keenly aware of the fragility of the mountain environment and zealously concerned for its protection. For three years, with a team of 23 experts - geologists, economists, sociologists, soils scientists, engineers - and several graduate students, including his son Cliff, he has been engaged in a National Science Foundation study of "The Impact of a Large Recreational Development on a Pristine Landscape." The model is the $20 million Chrysler Corporation-Huntley Big Sky Resort in the Gallatin Valley, where the Montagnes live.

The primary objective," he says, "is not to promote or prevent certain developmental activities but rather to establish a method of pre-examination of underdeveloped areas and thus predict what to expect from developments." His part in a new approach to the country's growing pains Montagne finds rewarding: We hope to come up with a significant contribution to developmental problems within a year or two."

Mindful of conflicting pressures to expand and curtail development with its strain on limited resources, he retains a cautious confidence in man's capability to live in harmony with his environment. "We are as close to crisis here in the mountains as others are in the cities. We can and must use our natural advantages while being, careful of catastrophic disruptions. I am optimistic that Man can begin to get along and hope to be part of promoting the how of it."

Of his own enviably integrated world, Montagne says "I could not hope for a more fulfilling existence than to be here now and doing what I am doing."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

June 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FIRST COED YEAR

June 1973 By Bruce Kimball '73 and Andrew Newman '74 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

June 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Goals and Purposes

June 1973

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

APRIL 1989 -

Cover Story

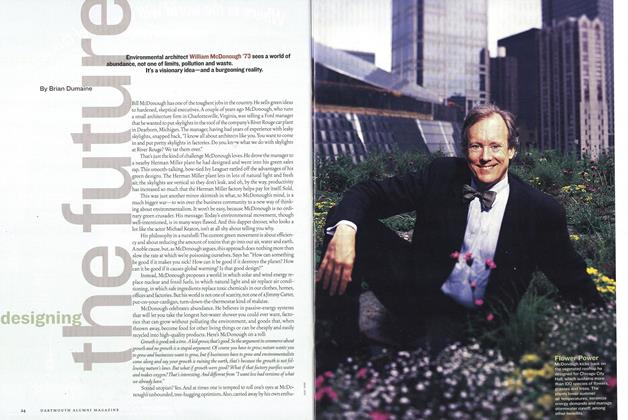

Cover StoryDesigning the Future

Sept/Oct 2002 By Brian Dumaine -

Feature

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Feature

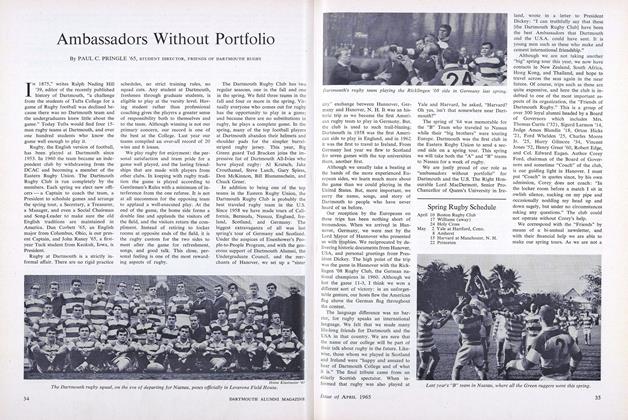

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

APRIL 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

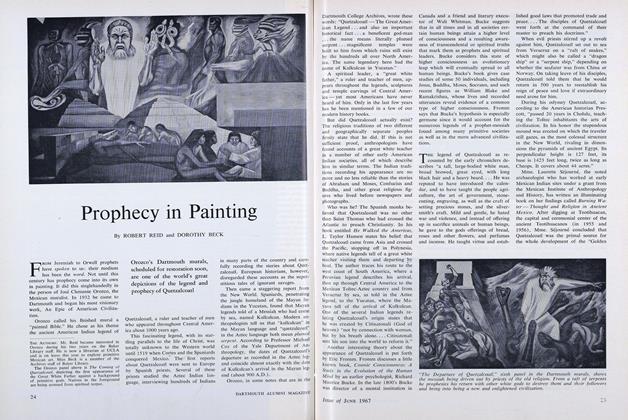

FeatureProphecy in Painting

JUNE 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN