ByRussell Fraser '47. Princeton University Press,1973. 425 pp. $l6.

Like all great arguments, Fraser's is so simple that to state it is to distort, perhaps to destroy it. The phenomena we associate with the Age of Reason - the rise of science, the drive towards the rationalization of art and society - all are characteristic of the Renaissance. The Modern Age, our age, began in 14th-century Europe (16th-century England): there we must look if we are to understand our own time.

By profession a teacher of literature, Fraser takes the fate of poetry as his central theme. What became of it in an age dedicated to reason and utility? Whereas the medieval poet had been expected to mingle delight and instruction with a promiscuity careless of form, the Renaissance poet found himself required to make an intolerable choice. Either his inventions were mere fictions unworthy of serious attention; or else they were truths, and must be subjected to the same deadly standards of clarity and utility as the truths of science and philosophy. Sinister fissures appear in the age that includes Boccaccio and Sir Philip Sidney. Traced out, they widen into the chasm that separates the tinsel kingdom of Art for Art's Sake from the industrial wasteland of Socialist Realism. At the bottom of that crevasse lies the corpse of true poetry.

The Middle Ages, as Fraser's most appealing chapters tell us, knew better. Theirs was a poetry (and a world-view) of inclusiveness, complexity, multiple levels of meaning, varieties of interpretation, opposites inextricably intermingled. Careless of form, contemptuous of decorum, the medieval took the world as he saw it, not as his reason told him it was - or ought to be. The great exemplars are Dante, Chaucer, and Shakespeare. Their vision of the world stands firm against a strangely assorted army of rationalizers; for Fraser's villains are not so much the traditional Enlightenment scapegoats (Descartes, Locke, Newton) as their more deadly precursors and offspring: grandfather Plato, who drove the poets from the Republic; Sir Philip Sidney, who gave away the battlefield to the enemies of art; and such a motley crew of contemporaries as Freud, Eldridge Cleaver, Rod McKuen, and Chairman Mao.

Brilliant, rewarding, paradoxical, often infuriating. Fraser defies capsule reviewing. I am in full sympathy with his point of view and persuaded by his arguments of its essential Tightness, yet doubts remain. The range of his allusions is formidable, but his pace is so fast that no one work ever comes entirely to life: much depends on our ability to take his word concerning Jean de Meun, John of Salisbury, Alanus ab Insulis, Samuel Daniel. The medieval temperament and its rationalizing opposite look in some lights like historic phenomena, in others like perpetual alternatives for the human spirit, more or less accessible in every historical milieu. Problems of mode and audience remain unsolved, or ignored: much of the book's fine polemic force is lost in the eighth and ninth chapters, where lit-crit threatens to submerge bigger issues; yet I suspect that medieval-Renaissance specialists will accuse Fraser of abandoning scholarly sobriety for the sake of polemic brilliance.

But for all my reservations, I remain astonished at the scope of Fraser's mind. Who could be expected to serve as readership for such a virtuoso piece as this? Fraser speaks - with calculated bravado, I think - of the man riding the commuter train home from business. Hopeless? Maybe: but in an age that looks to Barth and Pynchon for fictional entertainment, who knows? (The book, as a New Yorker critic would note, costs 16 dollars.)

A member of the Department of English,Dartmouth College, from 1960 to 1962, Mr.Cornell resigned to accept a position on theColumbia University faculty. He is now a residentof Hanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

June 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

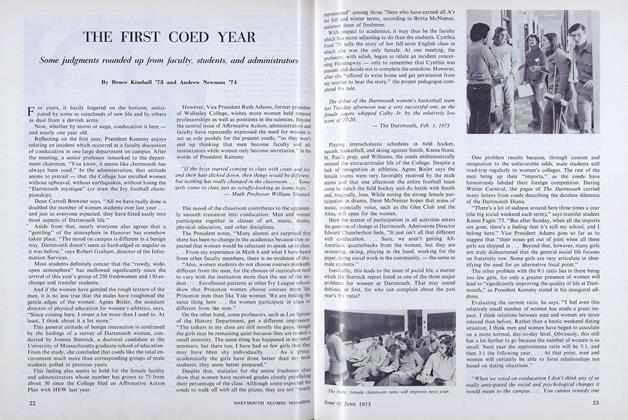

FeatureTHE FIRST COED YEAR

June 1973 By Bruce Kimball '73 and Andrew Newman '74 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

June 1973 -

Feature

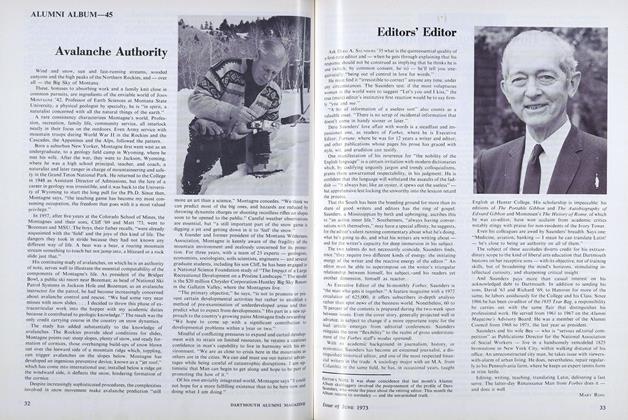

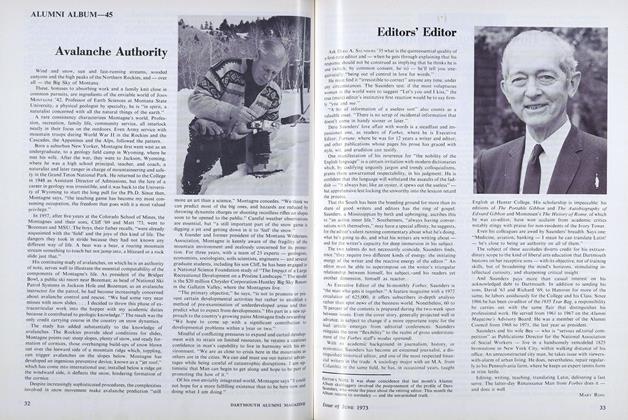

FeatureAvalanche Authority

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

June 1973 By MARY ROSS

LOUIS L. CORNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

OCTOBER 1965 -

Books

BooksTROUT FISHING

June 1950 By Albert H. Hastorf -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND SELF.

JULY 1963 By LLOYD H. STRICKLAND -

Books

BooksTHE ART OF SKIING. N. Y

March 1933 By N. L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksDISCOVERING THE GENIUS WITHIN YOU

JUNE 1932 By W. P. Chase