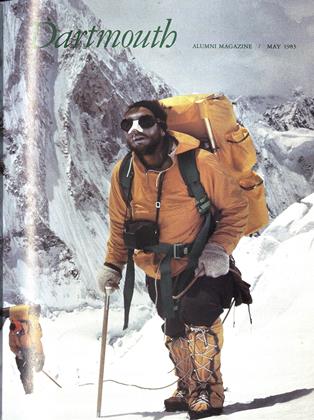

A recalling of the famous American expedition of 1963 and a check on what its Dartmouth members are doing now

By 1963, few Americans had been on Everest. It was considered a "British mountain," and nine of the first dozen serious Everest expeditions were British inspired and led. Finally, on May 29, 1953, Edmund Hillary and the Sherpa, Tenzing, planted their flags on the summit. Three years later, in 1956, a Swiss assault landed four men on top. (A Chinese armada claimed to have conquered Everest in 1960, but its account is sketchy and largely unsubstantiated. Many climbers think it was a snow job.)

Then, in 1963, an American expedition put six men on the summit. The first was James W. Whittaker, a Washington mountaineer, who planted the Stars and Stripes at 29,028 feet on May 1. Three weeks later, two other members of that team, Barry Bishop '53 and Lute Jerstad, an Oregon teacher and mountain guide, struggled up the same route to become the second and third Americans and the ninth and tenth persons ever to stand on the highest piece of geography on this earth.

Below Bishop and Jerstad, at various altitudes, were four other Dartmouth men one of them already buried forever, killed in an icefall accident.

In putting six men on the crest of the world, the Americans in their frozen boots pulled off one of the great coups in mountaineering history a two-route assault, with a first-ever Himalayan traverse. One set of climbers went up the South Col route, with a second set simultaneously climbing the West Ridge. The two groups planned to rendezvous on the summit and then descend together by the South Col.

The whole expedition was mountaineering on a grand scale. Twenty-seven tons of equipment, over 900 porters, 32 Sherpas, and the 19 Americans, who, incidentally, were a cerebral group. Among them were three M.D.'s, five Ph.D.'s, and five with M.A.'sorM.S.'s. The leader was a veteran mountaineer, Norman Dyhrenfurth, a 44-year-old American of Swiss origin, who had been on an earlier Swiss try at Everest.

Of the 19 members of this first American Everest expedition, five were Dartmouths: Barry "Barrel" Bishop '53, a geographer doubling as photographer for the National Geographic Magazine; Jake Breitenbach '57, a guide in the Tetons in Wyoming; oming; Barry "B. C." Corbet '58, also a Teton guide; Dave Dingman '58, a Baltimore physician and climber; and Barry "Bear" Prather '61, a geologist. A sixth member also had a strong Dartmouth connection: Al Auten was the younger brother of Hanford Auten '32.

No sooner had Base camp been established at 17,800 feet on the Khumbu Glacier than tragedy struck. Five climbers were in the treacherous icefall just above Base when masses of ice the size of box-cars shifted and crashed onto the climbers. Four survived, two of them badly battered, but Jake Breitenbach was crushed beneath the ice.

A pall fell over the camp and the climb. But the expedition had come too far to turn back. Jake's friends asked why and cried and got drunk, and then continued up the mountain.

Advance Base was established April 2 at 21, 350 feet, a pivotal site in the climb. From there, straight ahead, and up, was the Western Cwm (valley) leading to the Geneva Spur, the South Col, and the Summit. To the left was the alternate route up the "unclimbable" West Ridge, forbidding and unknown, to the same apex. In the weeks that followed, two groups, the South Colers and the West Ridgers, each plodded laboriously toward the sky.

On May 1, 1963, Big Jim Whittaker and his Sherpa, Gombu, gained the summit of Mt. Everest. The mountain had been won for another nation.

There was joy throughout the expedition, of course, but there was renewed determination among the others that more than just one would have a chance at the top of the world. All hands returned to Advance Base to recuperate and re-group, but they were soon back on Everest's precipitous slopes, hacking out campsites along the two routes, higher and higher in the thin air.

The West Ridgers were led by an anesthesiologist stick-of-dynamite, Tom Hornbein. He wanted to climb the West Ridge more than most people want to get to Heaven. No less tenacious was his alter ego, Willi Unsoeld, a professor of philosophy and Peace Corps director, who had climbed exensively with Hornbein.

Bishop, Corbet, Dingman, and Auten all worked on the difficult West Ridge route, but after a week, Bishop and Dingman joined the South Colers where more manpower was needed. ("Bear" Prather was grounded at Base Camp. Earlier he had developed pulmonary edema at Camp IV below the South Col, and only emergency doctoring by Dingman at 24,900 feet saved his life. The Bear had to come down the mountain.)

Hornbein and Unsoeld were left as the West Ridge summit team, Corbet having graciously withdrawn after he and Auten established Camp 5W. Corbet knew of the special relationship between the doctor and the professor, and "What's more," he said as he left them, "you're both just about over the hump and I'll be coming bacK again someday."

It was May 22. Hornbein and Unsoeld crept out of their tiny tent at 27,250 feet on the West Ridge, and on Everest's other face, Bishop and Jerstad left theirs, at 27,450. All four climbers were near the end of their ropes, literally and figuratively and their oxygen supply was dangerously low.

For Bishop and Jerstad the trek to the summit was painfully slow, and it was 3:30 p.m. before they reached the tattered flag Whittaker had planted three weeks earlier. They spent 45 minutes at the top, taking pictures while they waited. When there was no sign of Hornbein and Unsoeld from the direction of the Ridge, the two weary climbers began their descent.

What Bishop and Jerstad could not know, of course, was that Hornbein and Unsoeld were only a few hours behind. They struggled up the last few feet of the West Ridge at 6:15, saw the flag and the fresh footprints, and knew that Bishop and Jerstad had been there. They took their summit pictures in the fading light, and then felt their way via Barrel's and Lute's footsteps down the Col.

The hours passed and their flashlights dimmed. Desperately they shouted into the darkness, hoping against hope that Dingman and his support team might be looking for them in the night. Suddenly their shouts were answered, but instead of fresh help from Camp VI, they found Bishop and Jerstad, leaning on their ice axes, waiting for them, almost totally spent.

The four numbly joined forces, roped together, and stumbled down the mountain.

By midnight they could go no further. Their strength and flashlights were exhausted. They would have to bivouac. At 28,000 feet. Oxygen gone. Eighteen degrees below zero. No tents or sleeping bags. Just each other, huddled together in the snow and rocks. As they recalled later, each drifted off into fitful sleep only vaguely aware of the thin line between life and death.

Miraculously, the wind on the summit of Everest died down for that one night, and the four climbers survived.

They started down again at the light of dawn. Spotting them from below, Dingman and his Sherpa practically ran up from Camp VI to feed the stricken summiteers life-saving medicines and oxygen and nurse them down the slopes, from camp to camp. For the second time in a few weeks, Dingman saved his fellow climbers from death, and both times, like Corbet, he sacrificed his own chance for the summit.

Bishop, Unsoeld, and Jerstad all suffered frostbite. Bishop's and Unsoeld's were so severe that they were evacuated from Base camp by helicopter May 26, and each was hospitalized for months. Both lost all their toes and Bishop the tips of his little fingers.

Who were these five men, three from the far west and two from the midlands, who attended Dartmouth (altitude 531 feet), and who a few years later were fighting their way five miles up the world's highest mountain? And what has become of them since?

They all had one thing very much in common: they loved to climb mountains.

Barry Corbet, the only Dartmouth legacy (his father is class of 1921), was born and raised in Vancouver, B.C., and started climbing at the age of 11. He was active in Boy Scouts and the ski patrol.

Jake Breitenbach came from a small lumbering town in the shadows of the Olympic mountains in northwest Washington, and loved hiking, fishing, and "the rough outdoor life." The summer before coming to Hanover, he and his brother drove 10,000 miles criss-cross around the U.S. "seeing what the place was like.

"Bear" Prather did his early climbing in the small town of Easton, at the foot of Snoqualmie Pass, in Washington's Cascade Range. In nearby Ellensburg High School, he was a six-foot, 200-pound, a" state football player, with additional let ters in basketball and baseball. He came to Dartmouth wanting to climb mountains, play football, and be an engineer, in roughly that order.

Barry Bishop and Dave Dingman were a little closer to sea level in Cincinnati and Ann Arbor, respectively, but early on they got hills in their heads. A Boy Scout, Bishop summered in Colorado, and it was there that he met Henry A. Buchtel '28, president of the Colorado Mountain Club, who greatly influenced Bishop's climbing career. "Dr. Buchtel had me doing technical climbing by the time I was 12," he says, "and I knew Dartmouth was the place for me."

Dingman was a steady summer-camper in northern Michigan, and then he spent a summer in Colorado. "It was there," he says, "that I developed a keen interest in mountain climbing." In the next couple of years, by the time he was 17, he had climbed 16 significant peaks in the United States. But he had his sights on another height: he wanted to be a doctor.

Ihe eventual-Everesters had varying undergraduate tenures at Dartmouth. The shortest belonged to Bishop. He joined the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club right after matriculation, and was turned on both by it and geology." But he came down with pneumonia in February of his freshman year and withdrew from school. Back home, he enrolled in the University of Cincinnati, which had an excellent geology department, something Dartmouth was just developing in those days. Bishop got his B.S. in geology at Cincinnati, served in the U.S. Air Force (assigned to Rear Admiral Byrd's Antarctic Projects Office), and received his master's degree in geography from Northwestern University in 1955.

Corbet and Breitenbach stayed a couple of years in Hanover, with lots of time spent in the neighboring hills, and then headed back to the mountains of their youth. In a poignant letter to his parents about why he left school, Corbet wrote: "Dartmouth extols the well-rounded man. But I don't want some of my individual corners cut off."

He and Breitenbach went back to mountain-climbing, guiding and skiing, and they took part in several notable ascents in the Tetons and Canadian Rockies. In the summer of 1959, they (along with Pete Sinclair '5B) made an historic first ascent of the south face of Mt. McKinley at 20,300 feet, North America's highest peak. Later the two became partners in an inn and a skiing and mountaineering equipment store.

Dingman spent three years in Hanover, where he did some "moderate" undergraduate climbing, with summers as a guide in the Tetons. But "hitting the books" came first, and he transferred to the University of Michigan medical school after his junior year. He also pulled off a "first" on Mt. McKinley: in the summer of 1958 he organized and led the first ascent of both McKinley twin peaks in the same day a 22-hour climbing feat.

Prather admits that he did more climbing on the outside of Baker Library than he did studying on the inside. "We were forever climbing and rappelling around the campus," he recalls. "Bartlett Tower, Rollins Chapel, Baker Library, and the tallest dorms. I remember one night a group of us were coming down the side of a dorm, and the campus police appeared with their spotlights. 'What are you doing?' was the question. 'Rappelling' was the answer. 'Well, you'd better rappel your tails right back into your rooms' was the order."

Prather also played football, but between the pads and the peaks, his grades were not great, and he left school. He subsequently got his B.S. degree in physics from Central Washington State College and an M.S. from Michigan State in 1972. In the spring of Prather's freshman year, Maynard Miller of Columbia University, a noted geologist and glacier expert, spoke at the D.M.C. banquet in Hanover, and it was a signal event in the young man's life. Professor and student took to each other, and Prather has spent most summers since in the Juneau ice fields assisting Miller in polar research projects. Prather applied to the 1963 Everest expedition in 1963 but was turned down because, at 23, he was considered too young. But Miller, who had been signed on as a geologist/scientist, recommended Prather as his assistant. Thus, a D.M.C. banquet in 1958 put Prather on Everest in 1963.

No such Dartmouth network, however, brought five College climbers together on Everest. Breitenbach, Corbet, and Dingman had all known each other in Hanover, but it was their climbing exploits, not their alma mater, which led to their selection. Bishop, the veteran of the group, didn't know the others personally, but he did by reputation. Bishop's own was considerable: first ascent by the West Buttress route of Mt. McKinley in 1951, the Argentine Antarctic Expedition 1956—57, and an Himalayan expedition in 1960—61 that resulted in the first climbing of 22,494-foot Ama Dablam. Dartmouth itself was a "non-item" on the Everest expedition, according to all the participants. "It just never came up," says Corbet. The task at hand was all-consuming.

The Everest expedition cost Breitenbach his life. It also changed other members' lives. "Quite certainly," says Bishop, "Everest affected my life. The fantastic team effort established new friendships and cemented some old ones. The experience also reordered my values and priorities. It brought home to me philosopher Day Lewis's thought, 'A man should be judged not by the heights he reaches, but by the distance he climbs.' One hopes we have many Everests in our lives."

The climb was a turning point for Corbet, too. "Yes, Everest had its influence. It led to divorce, then re-marriage, and redivorce (same woman). It also led to a life in film work," he says, somewhat cryptically.

"The climb changed my life considerably," maintains Prather. "I found that mountains and glaciers can be observed, studied, and enjoyed in innumerable ways. I wouldn't have been chosen for Everest without Dartmouth and the D.M.C., and I'm stuck now with what it seems will be a life-long preoccupation: mountains and glaciers are hard to beat."

Not so, however, for Dingman, who says, "The expedition was probably not as big a part of my life as it was for many others. Because I had another profession and an overriding interest in medicine, Everest was only a brief interlude for me."

Was fame an element? Bishop says he made a conscientious effort to avoid attention and thankfully there wasn't much. Corbet remarks that notoriety is only for those who seek it. "Today," he says, "people tend to know me for what I do now, and it would be sad if it were otherwise." Dingman feels he is fairly well known as an Everester in his own circles for the simple reason that he is the only plastic surgeon in the country who has ever done any significant climbing. And Prather remarks whimsically, "People sometimes ask, 'Did you go with Whittaker?' I don't mind the question, though some might. Whittaker went with us, not we with him.

Today, 20 years after Everest, Bishop, Corbet, Dingman, and Prather have pretty much stayed with early goals. Bishop has had a long and distinguished career with the National Geographic Society. He is currently assistant to the president, acting as liaison between the society and the scientific and academic communities "to promote combined projects in research and education." He and his family have traveled widely; they spent two years back in Nepal and several summers in Alaska and the Yukon doing research. He is the author of over 20 articles and scientific papers, and he is a member of a score of professional and honorary societies. And he is now Doctor Bishop having taken his doctorate at the University of Chicago in 1980, at the tender age of 48.

Bishop, his wife Lila, and their two children live non-sedentarily in Bethesda, Maryland, whence they cross-country ski, Whitewater canoe, and backpack. The couple have climbed Mount Kenya, and as a family the Bishops have climbed recreationally in the Tetons and Seneca Rocks.

Corbet, who hoped someday to return to Everest, wrote a book in 1980, Oplions: Spinal Cord Injury and the Future. The dust jacket says, "Barry Corbet, prior to a helicopter accident in 1968, was a mountaineer, skier, filmmaker, hotelier, shopkeeper, father, and severely able-bodied person. He is now a kayaker, filmmaker, author, muckraker, father, and paraplegic. He lives in the foothills of the Colorado Rockies."

In 1968, five years after Everest, Corbet was filming from a helicopter when it unaccountably crashed into a mountain, breaking his back. Confined to a wheelchair ever since, he has produced or coproduced over 100 films, many of which have won prizes in festivals around the world. A number of his films emphasize disability and rehabilitation, and others, in his words, "have been effective tools for social change." He exchanged the mountains for water and is now a top class kayaker. A son, who is a senior in college, and his 17-year-old twins, a boy and a girllive with him in Colorado.

For Dingman, there was no contest between ice axe and scalpel. He never put the latter aside. He has practiced in Maryland, New York City, South Dakota (where he spent two years as chief of surgery at Ellsworth Air Force Base), and Salt Lake City, where he has lived since 1969- In 1976 he was a member of a rapidly mobilized team sent to Antiqua, Guatemala, where he helped set up a hospital in a football field to take care of all major earthquake casual ties in the area.

Dingman's love for the outdoors has never lessened. He skis regularly and is into running, including marathons. He has also taken to the waves and competes in the Tran-Pac and other long ocean races. His Cal-40 boat is berthed, at the ready, in Seattle. "I'm probably in better shape today, he says, "than I was at the time of Everest."

It is.no cliche to say that Prather has been a bear of a man every which way. He stil lives in Ellensburg, and, since Everest. he has climbed in Alaska and continued glacier research there every summer. He has been on four Arctic and Antarctic trips, .been married twice and fathered five children, been named the state's outstanding Farm Bureau and Kiwanis president, built his own house, become a volunteer soccer coach, finished his M.S. in geophysics at Michigan State, been a custom harvester for 16 years with his own combines, become a district Boy Scout chairman, and spent 15 years on the board of directors and as a trustee for the Foundation for Glacier and Environmental Research. And he has run a television appliance and repair service since 1973. "Looking back," he says, "I sometimes think my life has been a little nutty, but most of my activities have been normal in themselves."

Well over one hundred climbers have reached the summit of Everest since 1963, but the mountain is still claiming its share of those who tackle it. At least a half-dozen lives have been lost within the past year, including two of England's finest veterans and an American woman. No one ever summed up Everest any better than Bishop: "There are no real conquerors of Everest, only survivors."

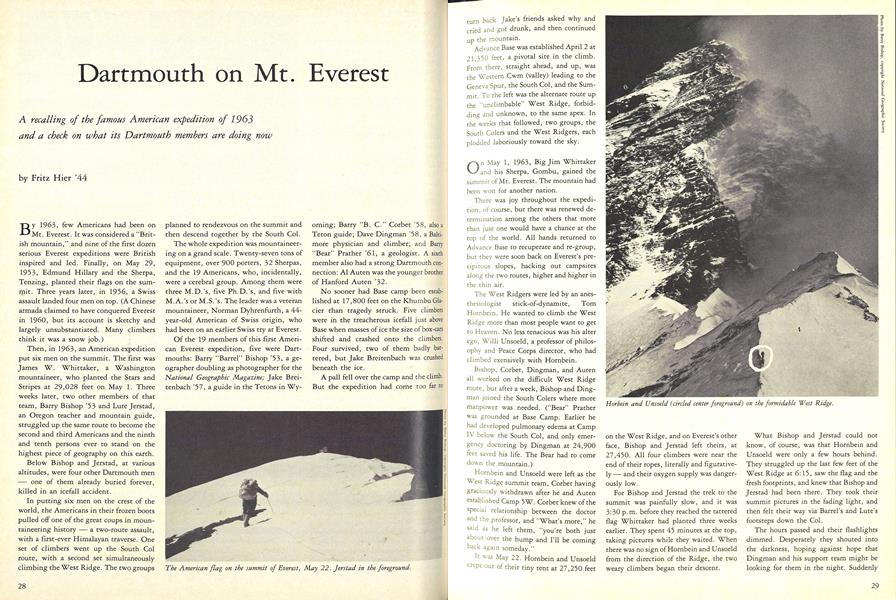

The American flag on the summit of Everest, May 22. Jerstad in the foreground.

Horbein and Unsoeld (circled center foreground) on the formidable West Ridge

Diagram showing how the two ascent routes separated at Advance Camp (21,350 feet). To theright, one route went up the Western Cum to the Geneva Spur, South Col, and summit. The other,to the left, went up the "unclimbable" West Ridge to the summit.

Barry Bishop '53

Jake Breitenbach '51

Barry Corbet '58

Dave Dingman '58

Barry Prather '61

President Kennedy congratulating the Everest climbers at the White House.

Barry Corbet, a paraplegic after a helicopter crash, is now a class kayaker.

Barry Prat her, shown with his second wife Kay, today presides over a large family. including fivechildren he has fathered and three step-children.

The Bishop family at home in Bethesda, Md.(from left) Lila. Brent, Tara. Barry.

Dave Dingman with his twin daughters Andraand Dagny.

Dartmouth members of theEverest expedition as theyappeared in 1963

Fritz Hier works for the College as Director ofPublic Programs, and has been climbing vicariously via books since childhood. He lives onLovejoy Hill, altitude 813' 6". in CornishFlat. N.H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

May 1983 By Jean Dalury -

Feature

FeatureBack to the Source

May 1983 By Matt Haley '83 -

Cover Story

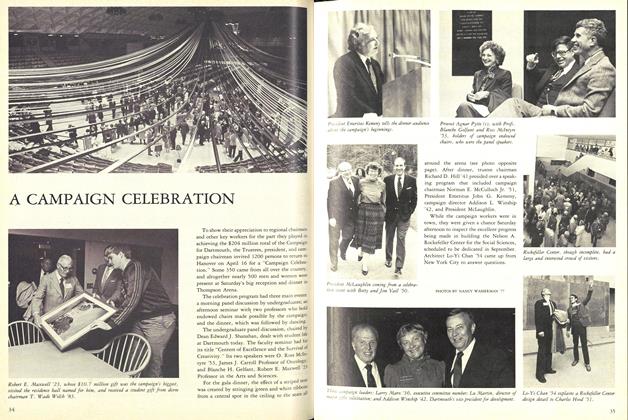

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

May 1983 -

Sports

SportsSports

May 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

May 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Greening of Labrador

May 1983 By Willem Lange

Fritz Hier '44

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

MAY 1990 -

Books

BooksTHE CATCH AND THE FEAST.

JANUARY 1970 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Article

ArticleHis Business Is Going Down the Hole

MARCH 1978 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Article

ArticleHow '44s handle 65 or, making the ice cream come out even with the chocolate sauce

NOVEMBER • 1987 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Feature

FeatureScions Of The Times

OCTOBER 1988 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleSabbaticals for the Rest of Us

April 1995 By Fritz Hier '44

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDecision Making

April 1975 -

Feature

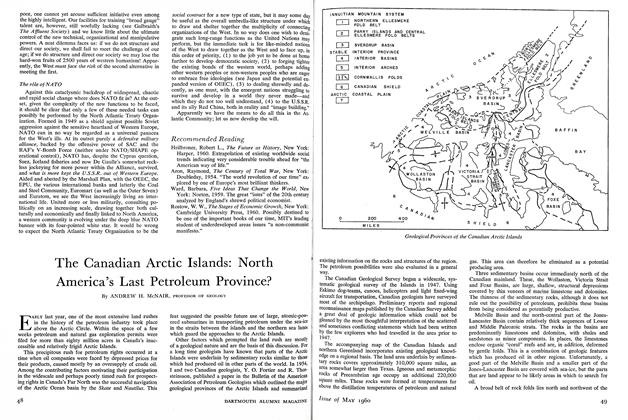

FeatureThe Canadian Arctic Islands: North America's Last Petroleum Province?

May 1960 By ANDREW H. McNAIR -

Feature

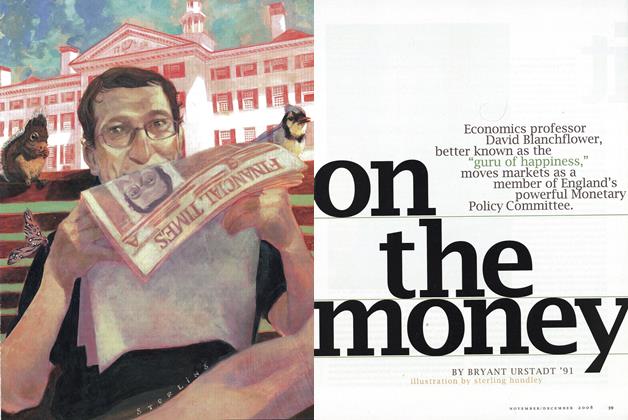

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

JULY 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

MAY 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch