As surely as if they had received actual diplomas, three famous New Hampshire women of the 19th century owed their education to Dartmouth College.

Laura Bridgman, considered by Charles Dickens to be one of the marvels of America, was born in Hanover in 1829. Probably few alumni are aware of Dartmouth's contribution to her achievements; most may not even be familiar with her name.

Laura was a normal, alert, and attractive child at birth, but at the age of two she was so severely affected by an attack of scarlet fever that she was never able to hear or see again. It was her good luck that a young Dartmouth student, James Barrett, Class of 1838, who was earning his way through college by tutoring, began to spend a few hours a week in the Bridgman home.

The study of psychology had not yet reached the Dartmouth curriculum, but Barrett's curiosity was aroused by the behavior of the pathetic waif who at the age of seven wore a folded scarf over her eyes and could only go outdoors when led by the hand. When not relegated to a chair in the corner, she often erupted into fearful tantrums in disputes over favorite possessions with her younger brother. So disturbed by this frustrated child and by the family's belief that she would shortly have to be sent to an institution because of her violent fits of temper, Barrett discussed the case with his professor of anatomy, Dr.Reuben Mussey.

Finding an excuse to visit the home, Mussey asked for a chance to observe Laura with a view to helping the family make its decision on her future. It was not long before he concluded that she was exceptionally intelligent, and he persuaded the family to let him bring Dr. Samuel D. Howe into the picture.

Howe's pioneering work with the blind was upsetting all the old theories and breaking new ground of discovery. Excited by the challenge offered by this remarkable child, he got permission to take her to his Perkins Institution in Boston for training. The ensuing experiments and sensational advances made in the case of Laura Bridgman revolutionized the treatment and education of handicapped children, and represented the first systematic education of a blind deaf-mute. And they were directly responsible for Annie Sullivan's later success with Helen Keller.

A few miles south of the Bridgman home in Hanover, another young woman was feeling the influence of Dartmouth's teachings. In Newport, in 1788, Sarah Josepha Buell was born into a home that was to provide the inspiration and cultural background that would lead her to become the outstanding woman editor of her day and an innovator of many of the progressive movements that we now take for granted.

To her brother Horatio Buell, Class of 1809, goes much of the credit for the appearance of Northwood, one of the first novels of consequence by an American woman. Sarah wrote it at the age of 39, when she was a widow trying to find a way to support her five children.

As a child, Sarah had been taught elementary subjects by her mother, but her thirst for knowledge would not let her stop there. Horatio spent his college vacations instructing Sarah in every course he was studying, even though it was generally believed at the time that higher education was too taxing for a woman's brain. Returning home with his Dartmouth diploma after graduation, Horatio brought a similar diploma for Sarah granting her the degree "Mistress of Arts, Summa Cum Laude," from "Horatio Gates Buell College."

"To my brother Horatio," she wrote years later, "I owe what knowledge I have of Latin, of the higher branches of mathematics, and of mental philosophy. He often regretted that I could not, like himself, have the privilege of a college education."

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale, editor of the famous Godey's Lady's Book from 1837 to 1877, was always in the vanguard of social progress for women. Hiding modestly behind a thin veil of Victorian decorum, she was able to bring about reforms in the study of medicine by women, property rights for women, child care, and nursery school training. A born challenger, she led drives for the completion of Bunker Hill Monument, the restoration of Mt. Vernon, and the establishment of a national Thanksgiving Day. Northwood was the very first novel to deal with the subject of slavery.

Six years before the publication of Northwood, yet another "Dartmouth-educated" girl was born, little Mary Baker, the last of six children. Always a restless and eager child, she begged her brother Albert, Class of 1834, to share with her the knowledge that he was acquiring at Dartmouth. He must have been as enthusiastic as Horatio Buell about his college experience, for he quite willingly gave Mary lessons in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

Mary was widowed soon after her first marriage, and in the years before she married Asa Eddy, she was forced to earn her living. Aside from sewing or teaching the ABC's, writing was about the only suitable career for a woman. Without the instruction received from her brother, she could not have qualified for this genteel occupation that propelled her into a life of letters, culminating in the publication of The Christian Science Monitor when she was 87 years old. Even her tremendously active and productive-life as founder and leader of one of America's great religious movements had its basis in the training she received at home.

Dartmouth will never be called upon to grant posthumous diplomas to these "graduates," nor should it single out just three. Many others benefited from teachings brought home by brothers and husbands in the decades when women were denied the right to attend college. In an unheralded way they helped pave the way for several hundred earnest students now on campus. May these young women prove to be as brilliant in leadership as the "sisters" of Dartmouth.

Like the subjects of her article, Olive Tardiffmarrying Joseph Tardiff '37, she was ateacher.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

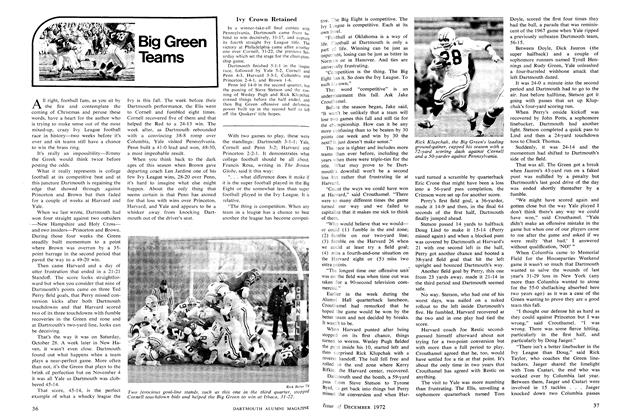

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

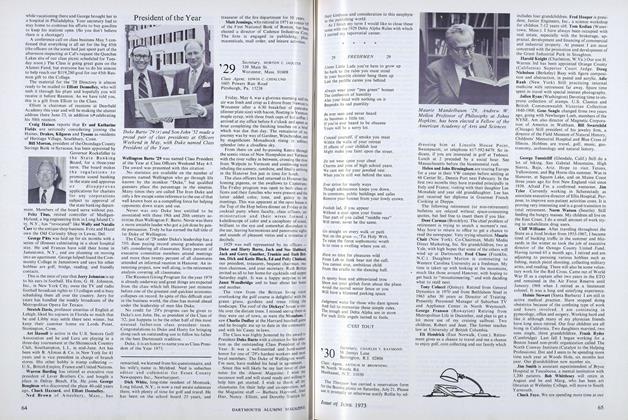

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER