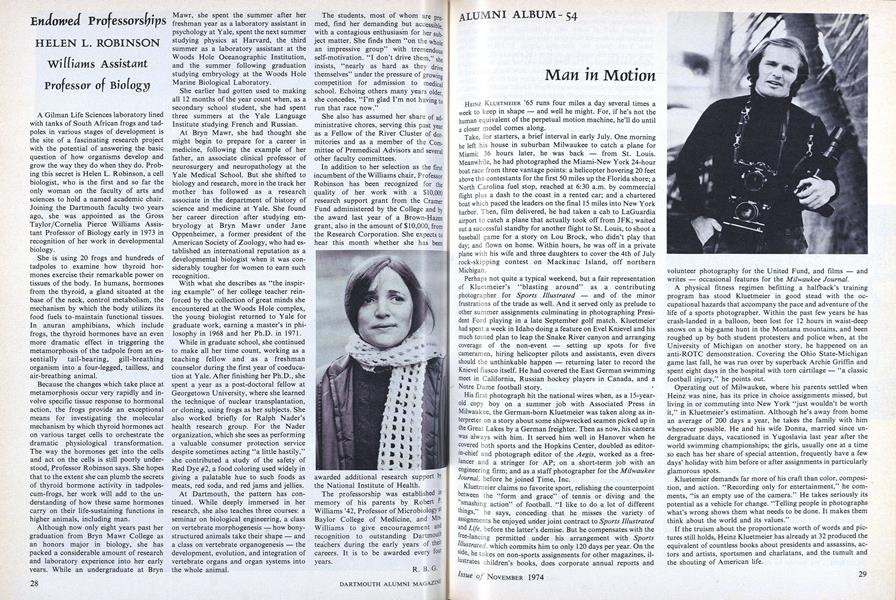

Williams AssistantProfessor of Biology

A Gilman Life Sciences laboratory lined with tanks of South African frogs and tadpoles in various stages of development is the site of a fascinating research project with the potential of answering the basic question of how organisms develop and grow the way they do when they do. Probing this secret is Helen L. Robinson, a cell biologist, who is the first and so far the only woman on the faculty of arts and sciences to hold a named academic chair. Joining the Dartmouth faculty two years ago, she was appointed as the Gross Taylor/Cornelia Pierce Williams Assistant Professor of Biology early in 1973 in recognition of her work in developmental biology.

She is using 20 frogs and hundreds of tadpoles to examine how thyroid hormones exercise their remarkable power on tissues of the body. In humans, hormones from the thyroid, a gland situated at the base of the neck, control metabolism, the mechanism by which the body utilizes its food fuels to-maintain functional tissues. In anuran amphibians, which include frogs, the thyroid hormones have an even more dramatic effect in triggering the metamorphosis of the tadpole from an essentially tail-bearing, gill-breathing organism into a four-legged, tailless, and air-breathing animal.

Because the changes which take place at metamorphosis occur very rapidly and involve specific tissue response to hormonal action, the frogs provide an exceptional means for investigating the molecular mechanism by which thyroid hormones act on various target cells to orchestrate the dramatic physiological transformation. The way the hormones get into the cells and act on the cells is still poorly understood, Professor Robinson says. She hopes that to the extent she can plumb the secrets of thyroid hormone activity in tadpoles-cum-frogs, her work will add to the understanding of how these same hormones carry on their life-sustaining functions in higher animals, including man.

Although now only eight years past her graduation from Bryn Mawr College as an honors major in biology, she has packed a considerable amount of research and laboratory experience into her early years. While an undergraduate at Bryn Mawr, she spent the summer after her freshman year as a laboratory assistant in psychology at Yale, spent the next summer studying physics at Harvard, the third summer as a laboratory assistant at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and the summer following graduation studying embryology at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory.

She earlier had gotten used to making all 12 months of the year count when, as a secondary school student, she had spent three summers at the Yale Language Institute studying French and Russian.

At Bryn Mawr, she had thought she might begin to prepare for a career in medicine, following the example of her father, an associate clinical professor of neurosurgery and neuropathology at the Yale Medical School. But she shifted to biology and research, more in the track her mother has followed as a research associate in the department of history of science and medicine at Yale. She found her career direction after studying embryology at Bryn Mawr under Jane Oppenheimer, a former president of the American Society of Zoology, who had established an international reputation as a developmental biologist when it was considerably tougher for women to earn such recognition.

With what she describes as "the inspiring example" of her college teacher reinforced by the collection of great minds she encountered at the Woods Hole complex, "the young biologist returned to Yale for graduate work, earning a master's in philosophy in 1968 and her Ph.D. in 1971.

While in graduate school, she continued to make all her time count, working as a teaching fellow and as a freshman counselor during the first year of coeducation at Yale. After finishing her Ph.D., she spent a year as a post-doctoral fellow at Georgetown University, where she learned the technique of nuclear transplantation, or cloning, using frogs as her subjects. She also worked briefly for Ralph Nader's health research group. For the Nader organization, which she sees as performing a valuable consumer protection service despite sometimes acting "a little hastily," she contributed a study of the safety of Red Dye #2, a food coloring used widely in giving a palatable hue to such foods as meats, red soda, and red jams and jellies.

At Dartmouth, the pattern has continued. While deeply immersed in her research, she also teaches three courses: a seminar on biological engineering, a class on vertebrate morphogenesis - how bony-structured animals take their shape - and a class on vertebrate organogenesis - the development, evolution, and integration of vertebrate organs and organ systems into the whole animal.

The students, most of whom are premed, find her demanding but accessible with a contagious enthusiasm for her subject matter. She finds them "on the whole an impressive group" with tremendous self-motivation. "I don't drive them," she insists, "nearly as hard as they drive themselves" under the pressure of growing competition for admission to medical school. Echoing others many years older she concedes, "I'm glad I'm not having to run that race now."

She also has assumed her share of administrative chores, serving this past year as a Fellow of the River Cluster of dormitories and as a member of the Committee of Premedical Advisors and several other faculty committees.

In addition to her selection as the first incumbent of the Williams chair, Professor Robinson has been recognized for the quality of her work with a $10,000 research support grant from the Cramer Fund administered by the College and by the award last year of a Brown-Hazen grant, also in the amount of $10,000 from the Research Corporation. She expects to hear this month whether she has been awarded additional research support by the National Institute of Health.

The professorship was established in memory of his parents by Robert P. Williams '42, Professor of Microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine, and Mrs.Williams to give encouragement and recognition to outstanding Dartmouth teachers during the early years of their careers. It is to be awarded every four years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: Food for Thought

November 1974 By MICHAEL STUART -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1974 By J.H.

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleROBERT E.GOSSELIN

November 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleERNST SNAPPER

January 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleS. MARSH TENNEY

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleGEORGE F. THERIAULT

June 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBenjamin Ames Kimball Professor of Administration

March 1975 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHANS PENNER

May 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMELVIN ADAMS CABIN FAST NEARING COMPLETION

May, 1922 -

Article

ArticleHonored for Service to Nation

February 1952 -

Article

Article$12,615

September | October 2013 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleSoccer and Cross Country

NOVEMBER 1965 By E.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Month

March 1936 By The Editor