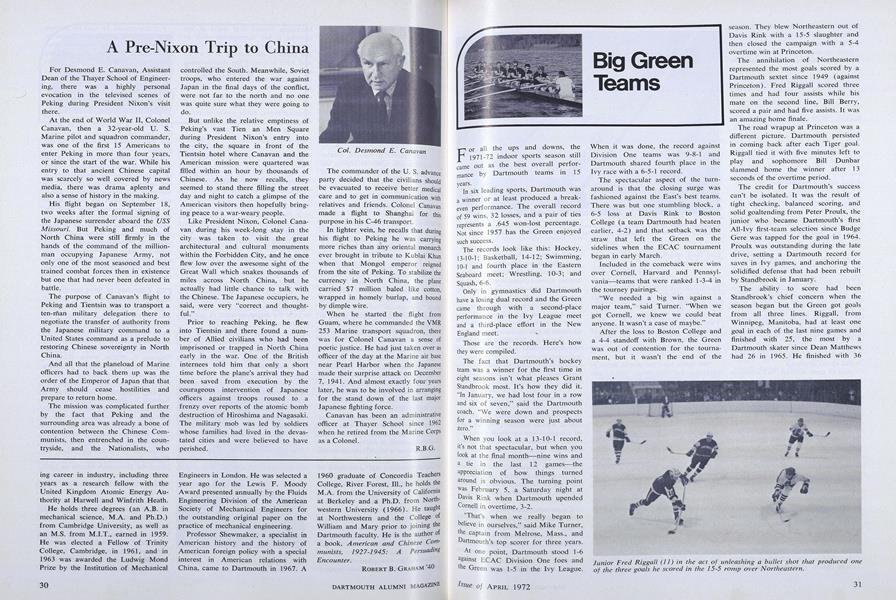

For Desmond E. Canavan, Assistant Dean of the Thayer School of Engineering, there was a highly personal evocation in the televised scenes of Peking during President Nixon's visit there.

At the end of World War II, Colonel Canavan, then a 32-year-old U. S. Marine pilot and squadron commander, was one of the first 15 Americans to enter Peking in more than four years, or since the start of the war. While his entry to that ancient Chinese capital was scarcely so well covered by news media, there was drama aplenty and also a sense of history in the making.

His flight began on September 18, two weeks after the formal signing of the Japanese surrender aboard the USSMissouri. But Peking and much of North China were still firmly in the hands of the command of the millionman occupying Japanese Army, not only one of the most seasoned and best trained combat forces then in existence but one that had never been defeated in battle.

The purpose of Canavan's flight to Peking and Tientsin was to transport a ten-man military delegation there to negotiate the transfer of authority from the Japanese military command to a United States command as a prelude to restoring Chinese sovereignty in North China.

And all that the planeload of Marine officers had to back them up was the order of the Emperor of Japan that that Army should cease hostilities and prepare to return home.

The mission was complicated further by the fact that Peking and the surrounding area was already a bone of contention between the Chinese Communists, then entrenched in the countryside, and the Nationalists, who controlled the South. Meanwhile, Soviet troops, who entered the war against Japan in the final days of the conflict, were not far to the north and no one was quite sure what they were going to do.

But unlike the relative emptiness of Peking's vast Tien an Men Square during President Nixon's entry into the city, the square in front of the Tientsin hotel where Canavan and the

American mission were quartered was filled within an hour by thousands of Chinese. As he now recalls, they seemed to stand there filling the street day and night to catch a glimpse of the American visitors then hopefully bringing peace to a war-weary people.

Like President Nixon, Colonel Canavan during his week-long stay in the city was taken to visit the great architectural and cultural monuments within the Forbidden City, and he once flew low over the awesome sight of the Great Wall which snakes thousands of miles across North China, but he actually had little chance to talk with the Chinese. The Japanese occupiers, he said, were very "correct and thought- ful."

Prior to reaching Peking, he flew into Tientsin and there found a number of Allied civilians who had been imprisoned or trapped in North China early in the war. One of the British internees told him that only a short time before the plane's arrival they had been saved from execution by the courageous intervention of Japanese officers against troops roused to a frenzy over reports of the atomic bomb destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The military mob was led by soldiers whose families had lived in the devastated cities and were believed to have perished.

The commander of the U. S. advance party decided that the civilians should be evacuated to receive better medical care and to get in communication with relatives and friends. Colonel Canavan made a flight to Shanghai for this purpose in his C-46 transport.

In lighter vein, he recalls that during his flight to Peking he was carrying more riches than any oriental monarch ever brought in tribute to Kublai Khan when that Mongol emperor reigned from the site of Peking. To stabilize the currency in North China, the plane carried $7 million baled like cotton, wrapped in homely burlap, and bound by dimple wire.

When he started the flight from Guam, where he commanded the VMR 253 Marine transport squadron, there was for Colonel Canavan a sense of poetic justice. He had just taken over as officer of the day at the Marine air base near Pearl Harbor when the Japanese made their surprise attack on December 7, 1941. And almost exactly four years later, he was to be involved in arranging for the stand down of the last major Japanese fighting force.

Canavan has been an administrative officer at Thayer School since 1962 when he retired from the Marine Corps as a Colonel.

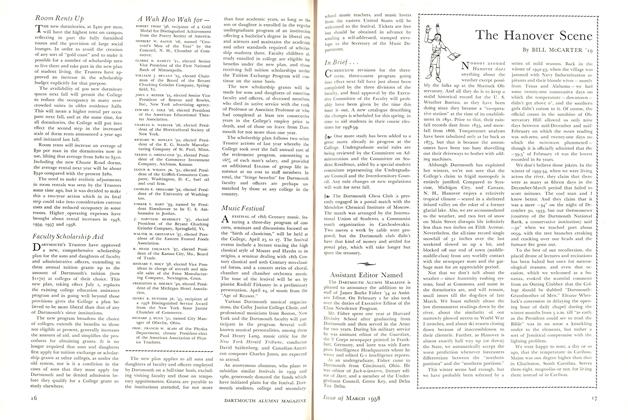

Col. Desmond E. Canavan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

April 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

April 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAdvocate for the Aging

April 1972 -

Feature

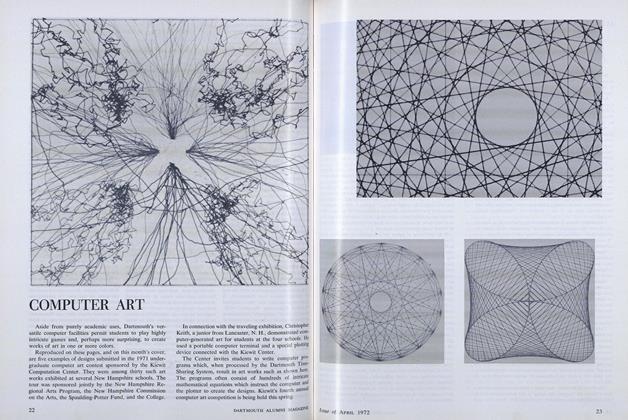

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

April 1972 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

April 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleIt's Still "Men of Dartmouth"

NOVEMBER 1972 By R.B.G. -

Article

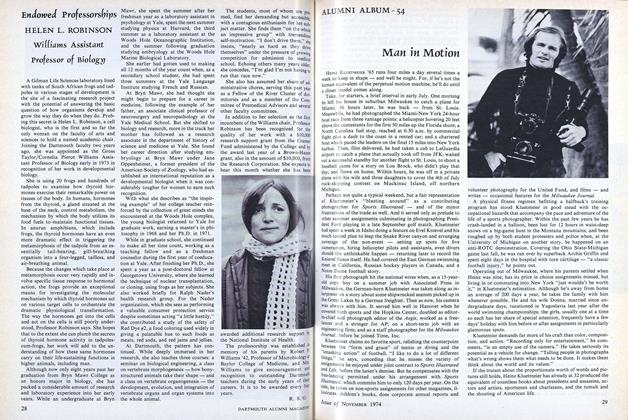

ArticleEndowed Professorships

MARCH 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJOHN W. FINCH

APRIL 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHELEN L. ROBINSON

November 1974 By R.B.G. -

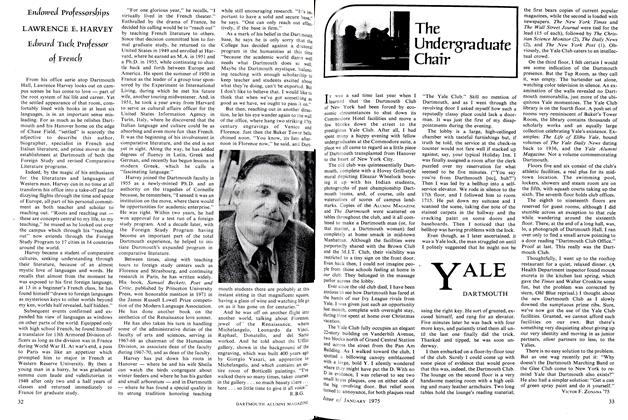

Article

ArticleLAWRENCE E. HARVEY

January 1975 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBenjamin Ames Kimball Professor of Administration

March 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleRoom Rents Up

March 1958 -

Article

ArticleStudents Assemble Drawings Show

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticleMASSACHUSETTS ALUMNI CLUB DINNER TO BE HELD IN MAY

APRIL 1986 -

Article

ArticleRecognition Factor

July/August 2005 By Andrew Mulligan '05 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES DARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES

January 1924 By Charles Sumner Cook '79 -

Article

ArticleProfessors At Play II. Present Day

February 1940 By Davis Jackson '36