RED POWER ON THE RIO GRANDE: THE NATIVE AMERICAN REVOLUTION OF 1680.

February 1974 FRANK JANNEYBy Franklin Folsom '28. Introduction by Alfonso Ortiz. Jacket and symbol illustrations by J. D. Roybal. Chicago: FollettPublishing Company, 1973. 144 pg. $5.95.

Almost a century before the American Revolution, which we often refer to as "the" revolution, a highly civilized group of peoples in the Southwest united, militarily defeated, and drove into exile the European oppressors who had forced colonial rule upon them. Within our present-day borders, the scene painted in Franklin Folsom's Red Power on the RioGrande: the Native American Revolution of1680, although in vivid contrast with that of our struggle with the English, is in essence much related. The "lobsterbacks" of our historical vernacular are here the "Metal People," as the Spanish colonizers were called by the Tewa Indians of southern New Mexico. Folsom cap- tures the essentially revolutionary nature of the New World experience while suggesting that for many of its inhabitants that bold era presented a threat and a challenge to maintain an Old World as time-tempered and sacred as that of the invaders.

Seen in this manner, Folsom's sympathetic portrayal of Indian revolution from the Indian point of view, with its symbolic setting on the Rio Grande, opens the door for a truly continental view of American history, closer to the rich multi-ethnic reality which somehow got overlooked by the early Makers-of-Text-Books.

Not that Folsom sets out to write history, although he has the documentation, or that he tries to make in any sense a Text, although his book is intentionally within reach of the young reader. To tell a story is the principal aim of the author, and to tell it from the "Indian point of view."

His tale begins with two young Indian runners, spreading the word of the impending revolution, learning that the plans have been betrayed to the Spanish. Doubling back to warn the war chiefs, they are later captured, interrogated, and publicly hanged. But the Spanish learn too late that a false date has been deliberately circulated; their headquarters are cut off; despite one desperate charge which takes the lives of 300 Indians, they are unable to break out. But after days of tension and hearing the taunt "God, the father of the Spaniards, is dead" shouted down at them from the hills, the tired and hungry Spanish population filed out of the gates in humilitation, flanked by rows of warriors. Despite the cruelties suffered under Spanish rule, the Tewas allowed their oppressors to depart without further warfare, thankful to be able to resume their life of milleniums beyond the shadow of the cross and the sword.

The quality that makes Folsom's book work is one of style. He has an action-oriented, non- rhetorical way of writing that nonetheless expresses, in simple words, the power and depth of Pueblo myth. It is an oral style for an oral culture - story as distinguished from history. He participates in the modern anthropologist's discovery that articulate, even poetic, hypothesis is more of a contribution to the reconstruction of early American culture than slavery to fact.

Since Folsom clearly states his purpose, to tell the story of the Pueblo revolt from the Indian point of view (a feat in itself considers that the original source material is from the Spanish records), it is not fair to accuse him of not being ecumenical. It is necessary, however, to add that the Spaniard comes off rather lowly in this portrait, true to the Black Legend which self-righteous (and slave-trading) nations created in the 17th century. If one is to contrast the admitted cruelty of Spanish rule in the New World, which nevertheless incorporated indigenous peoples into a religous and political system, with the slaughter and studied segregation practiced in our own system, the armored villain riding across the pages of Red Power loses some of his malevolence.

On the other hand, what good story lacks a villain? Indeed, from the indigenous point of view, the Spaniard with his war-house and steel arms (both unknown before the conquest) was at the least cataclysmic before bureaucratic and dogmatic, undeniably earning his role, as did the British officer who scarred Old Hickory's face for all of history.

Dartmouth Assistant Professor of RomanceLanguages, Mr. Janney teaches courses in LatinAmerican and Spanish literature. During the1972 winter term he took charge of theLanguage Study Abroad Program in Mexico.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

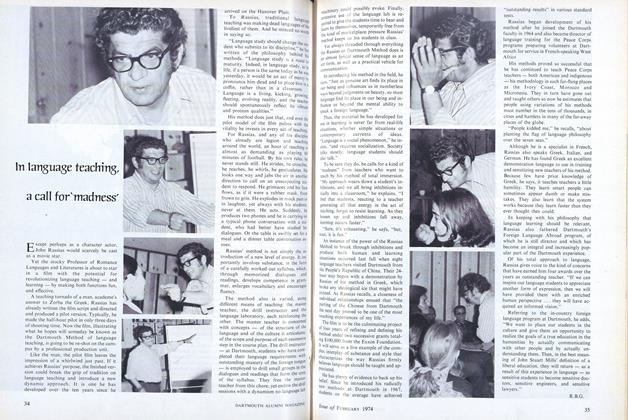

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleLatter-day Koster Man

February 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G.

FRANK JANNEY

Books

-

Books

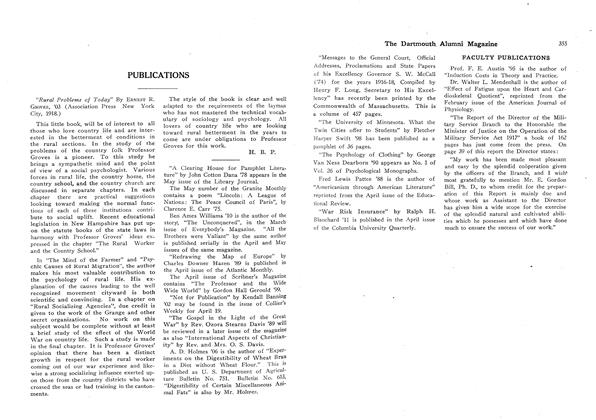

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

May 1919 -

Books

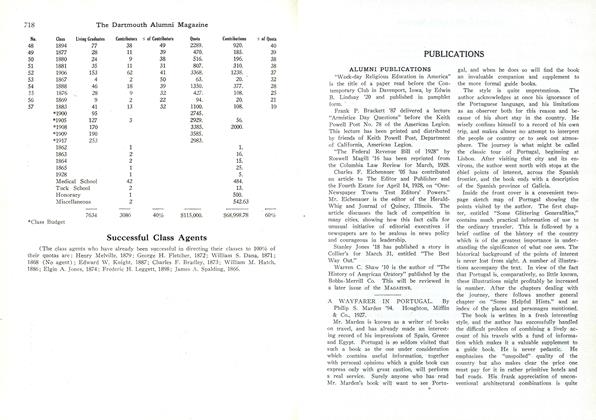

BooksA WAYFARER IN PORTUGAL

JUNE, 1928 By Ernest R. Greene -

Books

BooksDON'T COME CRYING TO ME.

February 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE TROUT FISHERMAN'S BIBLE.

JANUARY 1963 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26 -

Books

BooksPHILOSOPHY AS SOCIAL EXPRESSION

November 1974 By STEVEN T. KATZ