THE FORCE OF DESIRE

by William Bronk '38 Elizabeth Press, 1979. 74 pp. $14.00

THE BROTHER IN ELYSIUM: Ideas of Friendship and Society in the United States by William Bronk '38 Elizabeth Press, 1980. 244 pp. $14.00

The three long, analytical essays, one each on Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville, which comprise The Brother in Elysium, were written," William Bronk tells us in his preface, in the firm conviction "that much can be said about the nature-of society through the medium of these three American writers, who were so deeply concerned with society in both its immediate form of friendship, and in its wider form of our relations within the social structure."

Unaccountably, these remarkable essays were apparently allowed to lie in manuscript, unpublished, for nearly 35 years. Bronk began writing them, he tells us, shortly after his graduation from college and, having been interrupted by the obligatory years of military service in World War II, completed them in 1946. From that time to this the manuscript seems to have lain inert while Bronk went about the business of writing well over a dozen other books of poems and essays.

The Brother in Elysium, then, is in effect Bronk's first book. The Force of Desire is, say, his 14th depending on how one counts such things. In spite of the curious anomaly that the two should have appeared in print within mere months of one another, the voice that speaks in both of them is distinctively that of William Bronk; and the insights in both are uniquely, even idiosyncratically, Bronk's own, as recognizably so in his prose of 1946 as in his poems of 1980.

In The Brother in Elysium, the essay on Melville seems the clearest case in point. Most of Melville's major literary achievements, Bronk believes, resulted from the novelist's attempts to grapple with a metaphysical dilemma: the problem of evil, especially evil as it manifested itself in human society. Thus Melville undertook, in Bronk's metaphor, "an imaginary voyage in which he searched through the philosophies and social structures of the world for some frame of belief in which man could live in truth and dignity and freedom." Though the metaphysical voyage produced a stunning series of literary masterworks Mardi, Moby Dick, The Confidence Man, among others in the final analysis, Bronk concludes, it failed: "There was evil in the world and though it might be assuaged it could not be done away with. Where, then, was the final answer to man's social problem? There was no answer. . . . Evil was too persistent and man too equivocal for a final answer." Melville retired to the undemanding life of a customs inspector.

Even as he was nearing 70, however, he turned to face the ancient obduracy one final time. The result was Billy Budd, "the resolution and summary of the whole meaning and experience of his life." And Melville's "final answer," if answer it is, occurs in that final benediction pronounced on his executioner by young Billy Budd, primal innocence personified, in the instant before he was hanged: "God bless Captain Vere!" In that cry Bronk perceives Melville's own "great cry of affirmation and acceptance. For that little moment, in an irreparably evil and ambiguous world, ambiquity and evil with all their consequences were acquiesced in, and Jackson and Bland, Ahab, Claggart and Ishmael, and the evil Whale itself were drawn up and absorbed in a clear act of conviction and faith."

On the metaphysical continuum which he thus constructs for Melville, Bronk himself can be placed at present somewhere toward the end of the pre-Billy Budd stage. Or so, at least, the poems in The Force of Desire suggest to me. An "intolerable ambiguity" he called it in Melville's case. In his own he writes: "First, is to learn we have no power of our own,/Second, an Outside Power is impotent too./The strength we acquire is to live with power-lessness." In his new poems Bronk holds uncompromisingly to his lifelong central premise: If the world is not evil, it is at the very least ambiguous; it tells us nothing, expresses no secrets because it has no secrets to express. It has no order, no form, no truth except what we human beings choose to impose on it from the outside. It is not just unknown; it is unknowable: "These are invented words and they refer/to inventions of their own and not to a real world/unresembled, inexpressible."

There is much to admire in Bronk's position: intellectual integrity, tough-mindedness, wisdom even. But there is, as yet, no "God bless Captain Vere!" Perhaps there never will be. That is not to conclude, however, that Bronk's vision is intractably bleak. For always balanced against the inevitable failure of finite human desire is, as the very title of the book suggests, the splendid force of that selfsame desire. And so there is in Bronk's vision ample room for the human emotions. It is more salutary than depressing. In his cosmos the heart still yearns for meaning even though the head cries "Fool!" The poet is not immune to the yearning, the force of desire expressed in an expletive: "Mozart wrote as though it mattered as, of course,/ah well, it doesn't. Ah well, even so,/who puts it down? Yes, they do; I know." In one mood Bronk even seems, perhaps, to be working his way tentatively toward his own version of "God bless Captain Vere!": "We speak of weather, of course, but there/are climate changes. Time's limits and our/senses deny us things we know at heart."

Bronk still draws back, as if instinctively, from Melville's "clear act of conviction and faith." But allowing for the immense differences in idiom between a 19th-century novelist and a 20th-century poet, he comes close to it in The Force of Desire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

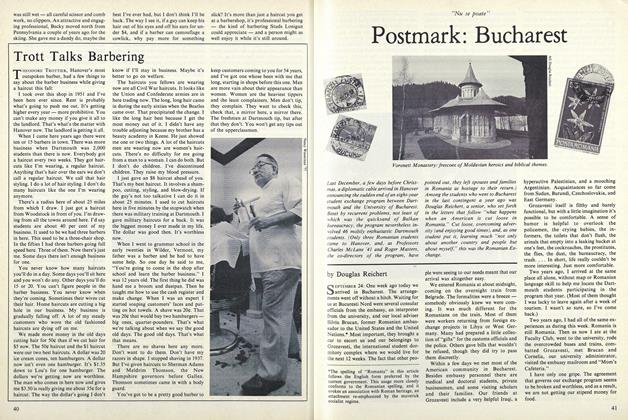

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66

R. H. R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on Mr. Eliot's Algonquian Bible, a Birthday Gift for Mr. Baker's Library

December 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSun to Sun

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMythogenic

JAN./FEB. 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksPoetic Institution

October 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWood Butchers

June 1981 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE LOGICAL SYSTEM OF CONTRACT BIDDING

October 1938 By C. H. Forsyth -

Books

BooksTHE DARTMOUTH SCENE

January 1950 By Charles A. Proctor '00 -

Books

BooksFore

DEC. 1977 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Books

BooksMINORITIES IN AMERICAN SOCIETY.

December 1952 By George F. Theriault '33 -

Books

BooksTHE GLORIOUS POOL

April1935 By Malcolm Keir -

Books

BooksFROM THE ISLAND

JUNE 1932 By R. L. Woodcock '33