Orvil E. Dryfoos Professorof Public Affairs

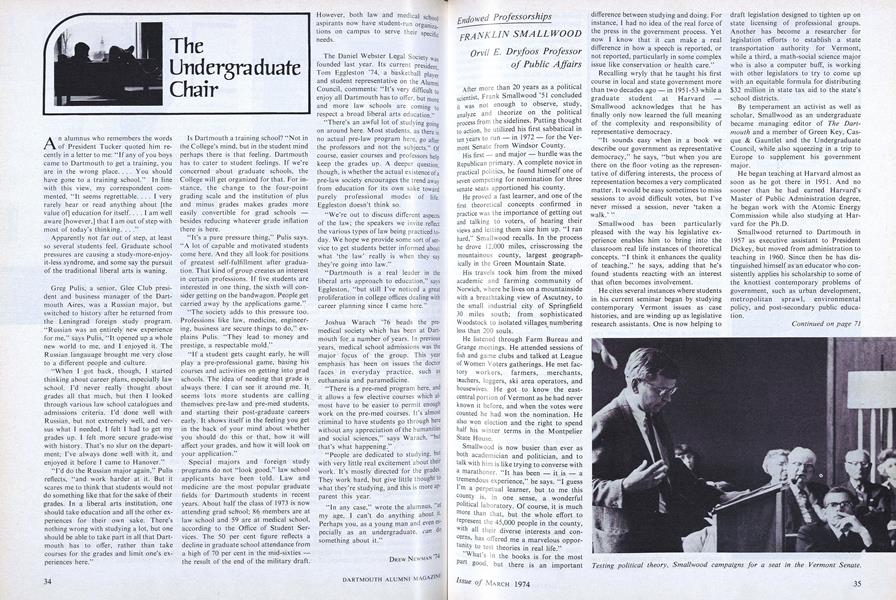

After more than 20 years as a political scientist, Frank Smallwood '51 concluded it was not enough to observe, study, analyze and theorize on the political process from the sidelines. Putting thought to action, he utilized his first sabbatical in ten years to run - in 1972 - for the Vermont Senate from Windsor County.

HiS first - and major - hurdle was the Republican primary. A complete novice in practical politics, he found himself one of seven competing for nomination for three senate seats apportioned his county.

He proved a fast learner, and one of the first theoretical concepts confirmed in practice was the importance of getting out and talking to voters, of hearing their views and letting them size him up. "I ran hard." Smallwood recalls. In the process he drove 12,000 miles, crisscrossing the mountainous county, largest geographically in the Green Mountain State.

His travels took him from the mixed academic and farming community of Norwich, where he lives on a mountainside with a breathtaking view of Ascutney, to the small industrial city of Springfield 30 miles south; from sophisticated Woodstock to isolated villages numbering less than 200 souls.

He listened through Farm Bureau and Grange meetings. He attended sessions of fish and game clubs and talked at League of Women Voters gatherings. He met factory workers, farmers, merchants, teachers, loggers, ski area operators, and housewives. He got to know the east-central portion of Vermont as he had never known it before, and when the votes were counted he had won the nomination. He also won election and the right to spend half his winter terms in the Montpelier State House,

Smallwood is now busier than ever as both academician and politician, and to talk with him is like trying to converse with a marathoner. "It has been - it is - a tremendous experience," he says. "I guess I'm a perpetual learner, but to me this county is, in one sense, a wonderful political laboratory. Of course, it is much more than that, but the whole effort to sent the 45,000 people in the county, with all their diverse interests and concerns, has offered me a marvelous opportunity to test theories in real life."

"What's in the books is for the most part good, but there is an important difference between studying and doing. For instance, I had no idea of the real force of the press in the government process. Yet now I know that it can make a real difference in how a speech is reported, or not reported, particularly in some complex issue like conservation or health care."

Recalling wryly that he taught his first course in local and state government more than two decades ago - in 1951-53 while a graduate student at Harvard - Smallwood acknowledges that he has finally only now learned the full meaning of the complexity and responsibility of representative democracy.

"It sounds easy when in a book we describe our government as representative democracy," he says, "but when you are there on the floor voting as the representative of differing interests, the process of representation becomes a very complicated matter. It would be easy sometimes to miss sessions to avoid difficult votes, but I've never missed a session, never 'taken a walk.' "

Smallwood has been particularly pleased with the way his legislative experience enables him to bring into the classroom real life instances of theoretical concepts. "I think it enhances the quality of teaching," he says, adding that he's found students reacting with an interest that often becomes involvement.

He cites several instances where students in his current seminar began by studying contemporary Vermont issues as case histories, and are winding up as legislative research assistants. One is now helping to draft legislation designed to tighten up on state licensing of professional groups. Another has become a researcher for legislation efforts to establish a state transportation authority for Vermont, while a third, a math-social science major who is also a computer buff, is working with other legislators to try to come up with an equitable formula for distributing $32 million in state tax aid to the state's school districts.

By temperament an activist as well as scholar, Smallwood as an undergraduate became managing editor of The Dart-mouth and a member of Green Key, Casque & Gauntlet and the Undergraduate Council, while also squeezing in a trip to Europe to supplement his government major.

He began teaching at Harvard almost as soon as he got there in 1951. And no sooner than he had earned Harvard's Master of Public Administration degree, he began work with the Atomic Energy Commission while also studying at Harvard for the Ph.D.

Smallwood returned to Dartmouth in 1957 as executive assistant to President Dickey, but moved from administration to teaching in 1960. Since then he has distinguished himself as an educator who consistently applies his scholarship to some of the knottiest contemporary problems of government, such as urban development, metropolitan sprawl, environmental policy, and post-secondary public education.

If Vermont is his focus now, his earlier concerns have been international in scope. In 1962-63, he conducted studies of the metropolitan areas of Toronto and London, and the fruits of these on-site investigations were two books, MetroToronto and Greater London: The Politicsof Metropolitan Reform.

In 1964, on a leave of absence from Dartmouth, Smallwood directed the opening phase of an international study of urbanization sponsored by the United Nations, and several years later continued this work as a U.S. delegate to the Delox IX Symposium on Urban Housing and Education held in Greece. There he worked closely with such other scholars as Margaret Mead to draft a resolution on that subject for the U.N. Conference on Human Settlement and Environment.

At Dartmouth, in addition to holding the Orvil E. Dryfoos Professorship and teaching his share of courses in the Government Department, he is chairman of the Dartmouth Urban and Regional Studies Program. He was an organizer and former co-director of the Boston Urban Studies Project, offered jointly by Dartmouth and and until recently also served as director of the Dartmouth Public Affairs Center.

Symptomatic of his many-faceted life, Smallwood also was the organizing codirector of the Environmental Studies Program. That program - largely patterned on proposals by Smallwood and Dartmouth biologist William A. Reiners - has since received national acclaim.

Somehow usually where action is, he was a member of the Hopkins Center Planning Committee when the concepts of that important arts structure were being hammered out. He served for a while in 1972 as acting dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, has twice been associate dean of the faculty and once chairman of the social sciences division, as Dartmouth has borrowed extensively on his organizational and administrative abilities. He has also served on the Executive Committee of the Faculty, is a past chairman of the faculty committee on athletics and has directed both the Class of 1926 Fellowship, Program and the Dartmouth Public Service Fellowship Program.

The Dryfoos Professorship was endowed by Nelson A. Rockefeller '30 in memory of Orvil E. Dryfoos '34, late publisher of The New York Times.

Testing political theory, Smallwood campaigns for a seat in the Vermont Senate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

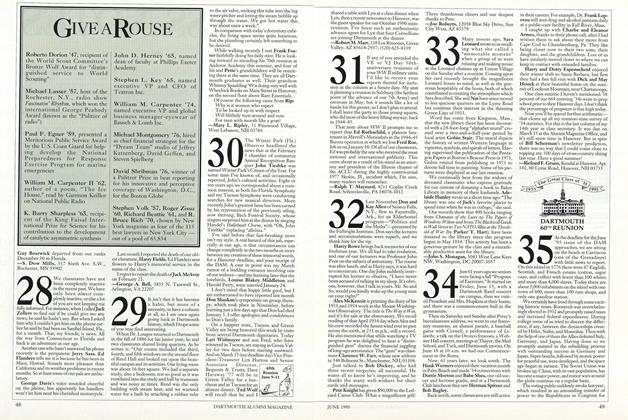

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON -

Feature

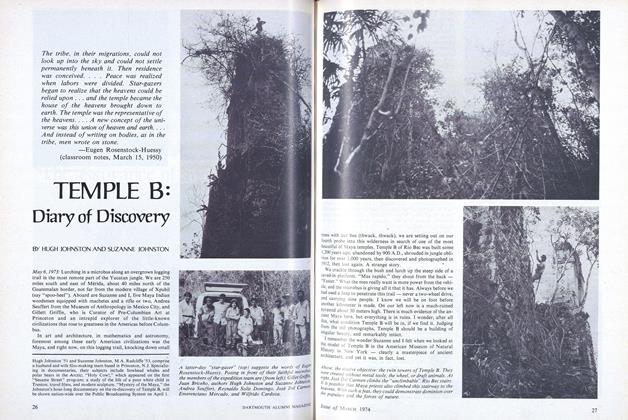

FeatureTEMPLE B: Diary of Discovery

March 1974 By HUGH JOHNSTON AND SUZANNE JOHNSTON -

Feature

FeatureConduit for the Faith)

March 1974 -

Feature

FeatureDelivery Man

March 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

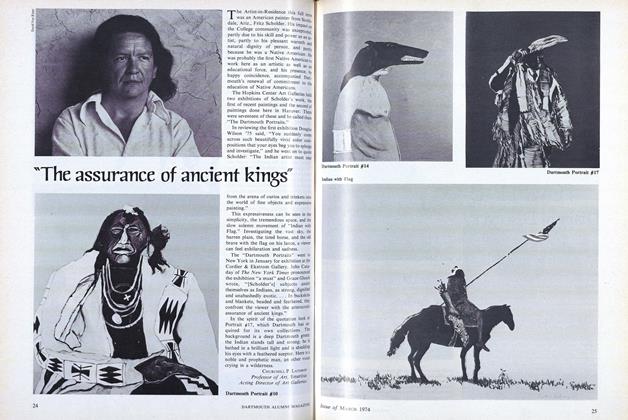

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Article

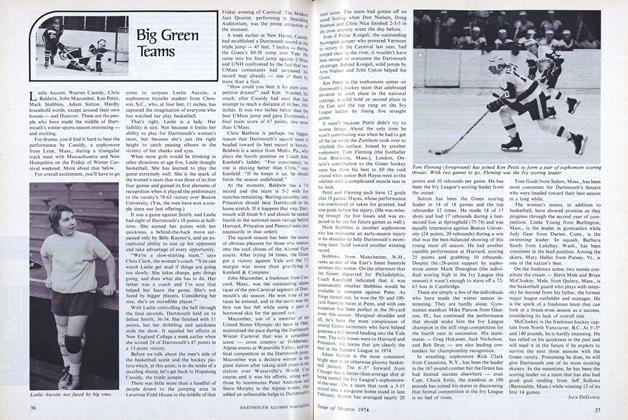

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1974 By JACK DEGANGE