Dennis L. Meadows is both Associate Professor of Engineeringand Associate Professor of Business Administration. Before joiningthe Dartmouth faculty in 1972, he was at MIT serving asrector of a systems analysis project on the "predicament ofMankind which was sponsored by the Club of Rome, an interzonalstudies group. The project resulted in publication of the celebrated - and and occasionally damned Limits to Growth. article also is adapted from a lecture given at theMinneapolis Alumni Seminar.

There are two ways to find out information about the future. One is to build computer models - that is an activity in which I engage - the other is to ask taxi drivers. I recently spent a good deal of time driving around in taxis and I asked every taxi driver, "What about this energy business? What do you think is going to happen? Is there really a crisis or is this just something the oil companies are foisting off on us? Is this some ploy by Nixon to divert attention from his other difficulties? How long is it going to last?" The consensus seemed to emerge from the taxi drivers that the energy crisis is not really a crisis; that it is somehow associated with the Middle East situation and that we can probably expect a settlement over there on some terms soon, the oil will flow again, and we can go back to business as usual. The taxi drivers don't anticipate gas rationing. They are not worried about running out of heating oil or natural gas. I think in this case the taxi drivers are wrong.

We all probably recognize that the decisions being made today will put in place a productive and consumptive system that will radically influence the quality of life over the next 50 years. It takes seven years to build a large power plant or a refinery. Once build those installations remain in place for 20, 30, 40 years or more and thus continue, once they are initiated, to exercise important influence on resource requirements, environmental standards, power availability over a period of three to five decades. Given that the decisions we are making today will have influences over that period, it stands to reason that we have to have some image of the future, some notion of our options and of our goals over the next 30-50 years if we are to do a very intelligent job with making the trade-offs that face us today. That stands to reason. It does not stand the test of politics, unfortunately.

Most of us would presume that we really have insufficient knowledge to think about a period of time 30-50 years from now. But each of us in fact already has enough knowledge to make some important statements about the future. There are five facts about our social, economic, and physical systems with which most of US would agree, and those five facts already tell us some very important things about the way that we should conduct ourselves as we sort out our various options.

The first fact is that we are in a period, both globally and nationally, of absolutely unprecedented material growth. That is growth in the absolute number of people, in the use of energy, in the rate at which we move materials (natural resources) through our economy. Man has been on this earth in something like his present form for at least a couple of hundred thousand years. During the vast bulk of that time man lived essentially in equilibrium, which is to say that an individual was born into a system very much like the one in which he died.

It has only been in the last 150 years or so that we have had growth and progress such that each individual during his own lifetime would see a doubling or quadrupling of the world's population, and a rise in material standards of several fold. Population growth today is proceeding at a rate which will cause the global population to double in roughly 35 years. That growth rate is accelerating. Birth rates are coming down, but death rates are coming down even faster. Material usage is growing at a rate which causes our total quantity of resources used annually to double every 15 years or so around the world. At least until very recently the same has been true about energy - doubling every ten to 15 years. There is growth in the non-material components of life as well - in knowledge, in cultural output, music, theater, those things which don't require the use of large amounts of natural resources. But the material growth, the demographic growth, clearly are proceeding at unprecedented rates. Inherent in these growth rates is an enormous momentum, which will sustain them for some time.

The second fact is that there are limits to material growth. There is a finite amount of arable land which exists, and the vast bulk of all of the usable, arable land in the world is currently being used today. Taking wildly optimistic estimates about how much land could conceivably be brought under cultivation, then we are using about half that; but in fact the half that we are using may represent 80 to 90 per cent of the potential in terms of inherent agricultural productivity. There are limits to the ability of the ecosystem to absorb material pollutants without deteriorating, and we see in many areas that the chemicals or materials that we are dumping into the environment have gone past those limits. There are limits to the productivity of the oceans in terms of the sustainable fish catch; we are very close to those limits in fact. Recently the global fish catch declined for the first time since World War II.

The third fact is that there are very long delays between the time that we take an action as an individual or as a society and 16 time when the full consequences of that action become apparent. There are further delays between the first perception and consensus about the desirability of these consequences, still further delay before we can initiate some effective response and additional delay before the response has had its full impact. DDT is a classic illustration. We began to release DDT into the environment in 1940. It wasn't really until the publication of SilentSpring that there came to be any widespread perception of the consequences. Silent Spring came out in the early 19605, so that was a delay of about 20 years. It took another 10-12 years before society, even in this country, came to some consensus that we were unwilling to accept the consequences of widespread, indiscriminate DDT use. Now we have implemented policies to curtail its use, but because of the physical processes - the biochemical processes - which cause DDT to move through the environment, there will still be significant quantities of it present in marine ecosystems, for example, into the next century. In fact levels of DDT in some areas may continue to increase for several years, simply because there is a lot of it in the pipeline that has not come down yet into the marine ecosystem. So even with this one simple illustration, we are looking at a delay which encompasses something like 80 years.

The fourth fact of concern with respect to this whole growing material and demographic system is the very short time horizons which are implicit in the vast bulk of economic, personal, and political decisions. It's very interesting to categorize the information in the newspaper for our own decisions in terms of the time span inherent in them. Over what period do we think about costs and benefits when we choose between alternatives? In most cases we can explain decisions being made today without looking farther than a few months or a few years ahead. Certainly the evolution of our energy policy in this country has been based on rather narrowly defined and short-term considerations: "We should keep the price of natural gas down over the next few years." But what does that mean for ten or 20 years into the future? "We should switch to nuclear reactors because they don't put out so much pollution today as do coal-fired plants." Of course, 15 or 20 years or 2,000 years from now there will be a great deal more pollution, potentially, as a consequence of nuclear reactors, but that is not considered.

The fifth fact is that many of the resources on which this growth is based are erodible. Arable land is erodible in many ways. Some rather crude data suggests that the amount of land which has disappeared over the last 50 years from the category of arable, usable land is something like ten per cent of the earth's dry land surface. That much has been destroyed through careless activities of man, often coupled with the effects of weather. Obviously, oil is an erodible resource. Every gallon we use is a gallon not available to us or our children in the future. Some of our lakes are erodible in the sense that once we cause them to eutrophy, it may take a very long time indeed before they can come- back to earlier levels of productivity.

Now, if you accept these five facts as being characteristic of our economy and our society, then you also have to accept some rather unwelcome conclusions which follow directly from these facts. The conclusions are that the system is unstable - which is to say that it will not evolve in a nice, orderly fashion. It will tend to overshoot sustainable limits. It will tend to go past what might be considered desirable long-term levels. Given the erodible resource bases, there is an inherent tendency for what we call overshoot/collapse: a system will tend to go far above sustainable levels, stay there for a moment, meanwhile madly eroding its resource base, and then fall back. Energy has each of these attributes: growth, limits, long delays, short time horizons, erodible resources. So do the other important aspects of our society - production of food, the evolution of our political institutions, etc.

In some very important ways we really are like passengers on a, ship where the many captains up on the bridge first of all cannot agree on where they are going; secondly, are so nearsighted that in any event they only look five or ten feet in front of the bow; and who respond to every problem by accelerating the vessel. I have been amused at how often the pronouncements about our ability recast the future have really taken the following form: "We can't say anything about the future, therefore full speed ahead."

Now the ship is an interesting analogy for a number of reasons: first, I think most of us would not tolerate that situation if we were on the ship. Were we to find ourselves out on a vessel like that, the first thing we would do is to try to decrease the tendency to collide with something, to slow it down, to buy a little more time to decide where it is we are going, how we are going to get there. This would often be difficult, particularly if the ship has been out in open sea for a long time with no obstacles, because the captains will have come to have a very high opinion of their ability to navigate without incident. So slowing down would be the first policy" that we might urge. Obviously, it also would be important to force some consensus on the long-term goals of the vessel, to have some idea of where it is going. Then, if it's impossible to physically overcome the myopia of these captains, we should augment the information available to them with a device like radar; that is, a device for projecting the future consequences of current speed and current course of the ship.

How do these rather general concepts of the facts and their implications and the solutions assume any concrete meaning in the energy system?

It is useful to start with physical growth, and to attempt to portray its dimensions and some of the factors which may influence it in the future in the energy sector. We still are growing demographically in this country, although family sizes have at least temporarily reached replacement levels where each couple has on the average two children. Still, there is an enormous momentum inherent in the age structure of our population because we have so many young people who haven't yet had their "fair share" of children.

In food we find similar pressures. There are two ways to increase food production. The first is through expanding arable land area, the second is by using capital inputs - chemicals,pesticides, fertilizers - more intensively. Since the 19505, themajor expansion in global food output has come through the intensification of agriculture rather than through the expansion of land area. There is still some possibility of expanding land area,but the bulk of the gains will have to come through intensification. But it has been estimated that to double food productionover the next 30 years globally would require us to put in perhapssix times as many pesticides as we currently use. The fertilizer estimates would be similar in magnitude, and we would have to usemuch more fuel for tractors and other machinery. The otherpressure on food, of course, is that we have been historically moving farther and farther up the food chain, which means that wetake on protein more and more in secondary forms - in the formof beef rather than oats or corn. There is a great loss in thatprocess. It takes about seven calories of vegetable protein toprovide one calorie of meat protein, and with increasing affluence - with escalation in the demands for meat, eggs, milk - thedemands for food output have been going up even faster than thePopulation.

Pollution abatement also argues for greater energy demands in the future. Pollution is, in a sense, a resource which has become so diffused, either through the air, in soil, or in the water, that it is no longer possible to concentrate and use it effectively. Or else it is material which is in the wrong chemical form to be of use. In either case, pollution abatement or recycling often imply putting a good deal of energy into the pollutant in order to make it either less widely distributed or again useful. As we push our environmental concerns then, there will be pressures to increase our energy use per capita.

The limits in other areas of resources are somewhat farther away. We have an enormous amount of coal in this country which will be useful if we can find ways of extracting, processing, distributing and consuming it in ways that are economically and environmentally acceptable. We currently mine about 500 million tons of coal a year. Estimates of the amount of coal available in this country are 3,000 billion tons. Much of that probably will not ultimately be extracted, but it's reasonable to think that we could shift to a substantial reliance on coal and use it for a period of 50-100 years without pressing coal resources to their absolute limit. Uranium is a finite resource, but if coupled with breeder reactors it could conceivably provide a power source that had few effective resource limits. There are many other limits, however, that we should be concerned about with fission and fast breeder reactors.

There are other limits in the energy system which are not receiving very much attention today but which are of extreme importance. In addition to the physical limits, there are also social and psychological limits. There is some limit to the gap which can be maintained between the material - the energy - standards of the rich and the energy standards of the poor, particularly as the instruments for retaliation become more widely available. The hijacking of airliners to gain certain advantages in the Middle East between the Palestinians and the Israelis is just a very small example of the sort of things that we could expect in the future. The gap between rich and poor is enormous, and is currently increasing in absolute terms. So there is reason enough to be concerned about our ability to maintain a very high level of energy consumption, which means high-level material comforts here, in a world where 50-80 per cent of the people live at standards enormously lower than our own.

There are psychological limits - the limits to our ability to organize and control large technical, economic, and social systems. It may be that some of the schemes now considered for the generation of energy in the future will simply go beyond our organizing capabilities. There are other kinds of psychological limits. Every time larger and larger systems are adopted, people become more and more divorced from the control over their lives, from any useful identification with the products of their labor. It's interesting to speculate about some of the labor troubles arising in Detroit where the absentee rates, the strikes, the disruptions are really enormous by almost any standards.

The third fact with respect to long delays can be demonstratea in much more concrete terms. We have been engaged now for 25 years in an extraordinary effort to bring atomic energy into widespread commercial application. Stop to think about the AEC and its development program, the many AEC labs, the amount of money which has been poured into this effort, the degree to which the technology has been insulated from social controls. Recognize that we have, after 25 years, only a very small fraction of our energy coming from nuclear power. This begins to give some insights into the kinds of delays that we face in this area.

Some work that we have done suggests that if we begin a terribly anxious, very well-coordinated, very farsighted effort to expand our use of coal, under the best of circumstances, by the year 2000, we still will probably be making less than 50 per cent of our energy from coal. A number which is bandied about among those in the field is that if we marched right along with fusion power, the feasibility of which has not yet been demonstrated, it still would be 2050 before we could expect to have a very significant fraction of our energy coming from sources like that. Even where the technologies are relatively mature and where it is no longer a factor to invent the device, there are enormous delays in implementing it. Every time changes are made in the energy system in this country, such actions have enormous rewards for some, but very great penalties on others. For example, oil companies or automobile companies - people and institutions of all kinds - that have an enormous power in this country and which, for reasons easily enough understood if not appreciated, are quite willing to do everything they can to block change along directions which they perceive as being against their short-term interests. The interconnectedness of the system also makes it difficult to change very quickly. For example, if we were to begin gasifying and liquifying coal out West and in piping it East, water would have to be found in enormous quantities - either taken away from other uses or brought down from Canada. Negotiations of that sort again are not ones that are completed very quickly.

There are rate constraints. The power sector of our society accounts for something like 20 per cent of our gross investment. To turn the power system from conventional thermal steam plants to a different source based perhaps on coal gasification or liquification or on more esoteric forms, would involve capital investments which are enormous by any standards and which cannot be brought about instantaneously. It will take many, many years to slowly accumulate the capital stock necessary to implement these new devices on any broad scale.

There is a question of moving people around. Just as one example, we have come through a period of 30 years during which the coal labor force has been slowly declining. The coal industry is geared to a point of view where it is not hiring people on the net; it is in fact displacing them, letting them retire or actually laying them off. Forty-one per cent of the coal labor forces retire within the next ten years. Any program to expand coal production significantly implies bringing large numbers of people back into this industry. That means training them, getting them to think mining coal is a desirable activity, getting them to move. Those things are not done quickly.

Finally, capital has its own natural cadence. For example,just on such a simple job as installing stack-gas abatement devices where the technologies are relatively well in hand we find rate constraints. It's best to install these things during periodic checkups when the power plants are shut down and gone over rather thoroughly. These checkups don't occur very often, and to examine all the plants that need these abatement devices an schedule time to get to them, one would begin to look at a rather extended time period.

At the moment something like 80 per cent of our power is coming from fossil fuels. Oil and gas, because of depletion. will begin to decline in their importance and we can expect them tp peak out somewhere between now and the year 2000. Under the best of circumstances the so-called ultimate sources, the sources which are not constrained by fuel - fusion, thermal, solar - really cannot be expected to have a significant influence much before 2050.

why do we have this short time horizon? Well, in the energy system it's been easy to have a short time horizon because we have had such an abundance of resources - at least apparently - and in the short term there has been little incentive to do any long-term planning. We had a lot of gas, a lot of oil and coal, and and so there just never seemed to be incentive to sit down and really start thinking about how these resources were going to be used That short-sightedness has been made somewhat easier bu the nature of our political system. By political I mean public and private administrative decision-making. It happens to be the case that in industry and in government people occupy positions for relatively short time periods and have an undue incentive to do things which will appear very attractive by the time they leave those positions, and, in the same fashion, to choose decisions whose costs will only become apparent at some later time.

One of my favorite illustrations of this is a story which is true and which comes from the board meeting of a very large Midwest electric utility. The members were attempting to decide whether their next facility should be nuclear or dependent on natural gas. It was pointed out to them that well before the expected lifetime of this facility had come to an end, gas would be essentially depleted in this country and therefore some other strategy might be more appropriate. The response to that was: "It may well be, young fellow, that natural gas will run out before our facility is finished, but I will be out of here before the natural gas runs out. Nuclear power has harmful consequences for me in the short term because I will have a great deal of static from the environmental groups. The technologies are not yet perfectly developed and there is potential for construction delays and technical problems, and over the time period of interest to me the natural gas alternative is the one that appears superior." This should incidentally not be taken as an argument in favor of nuclear power, but it nicely illustrates the fact that even in industry the incentives can be such as to force a very short-term perspective.

In the public sector, of course, these issues are much more apparent where short-term electoral cycles force one to come to some kind of terms with the consequences of his decisions within a two- to four-year period.

Let's assume that we have two policies in question. Policy A has as its dynamic-consequence-over-time a negative effect. Policy B has as its dynamic-consequence-over-time a positive effect. An election is held at a point when the short-term consequences of policy A appear preferable. There is hardly any government official, given this pure choice, who could find himself the rationale for electing that position which is worse in a short term but which has some longer term benefits. I know that even if I were an altruistic and dedicated public servant I would probably reason, "What good does it do me to make this decision, because I will just get voted out of office, and the shortsighted fellows that come in after me will just reverse what I have done, and not leave society able to capture the benefits." This is a very serious dilemma and one of our problems is to work out some augmentation to our political system, which does have a great deal of flexibility in it, that will begin to provide the sort of incentive to lead short-term decision-makers to bank somewhat more on the long-term consequences.

Now, given that the energy system is richly endowed with all of those attributes which cause overshoot and decline, or which cause a disorderly evolution, what can we do about it? I return to the three policies that appear appropriate in the context of the "ship."

First, slow down. In each of the following cases it's clear that while some governmental action can move us in the appropriate direction, individual initiative is also required. There really is - a tendency in our society - perhaps increasingly with the size of these issues and their time horizons - to view the problem, conclude that you can't solve it by yourself, and then simply to walk away. If everyone does this, then the problem is not effectively addressed. If one can define a solution to the problem, however, so that if everybody else also did it the results could be satisfactory, then perhaps we can begin making some constructive contributions.

How can individuals decrease their power consumption? I guess the first thing is to simply find out what it is. How many people know how much electricity they used last month? It's made rather difficult to know. The meters are not for your benefit. They are for the benefit of the electric company. I suggest that you might keep a little graph, and engage your children in the process of measuring the power that flows through the household every month. Then start seeing what can be done about it. I predict that there is at least 20 per cent pure fat in that consumption which could, over a period of six months or so, by changes of habits and perhaps a slight reduction of the thermostat, be eliminated. This is just an example.

The second solution mentioned was the development of some long-term goals. There is no way of making a rational choice among various energy alternatives until we begin to have some image of our family, our state, our country 20 or 30 years from now, during that time when the current decisions will be having their full impact.

There are many different kinds of United States that we could envision in the year 2000, and if we go out even a little further to 2020 an even wider variety - all within political and physical constraints that we can think about. Which of those do we prefer? Do we want to continue centralizing our populations? Would we like to redistribute them once again into rural areas? Are we satisfied with the trend towards mass consumption and a highly industrialized society, or do we prefer to decrease some of those trends and emphasize consumption that is in other sectors? We have almost no influence over those things in the short term, but over a 50-year time period there is a great deal of flexibility, and it's possible at all levels to begin thinking about options and forming some consensus.

Without that long-term image, which has to be directly dedicated to a stabilization of our population and our material and energy use, there is no possibility in this country of avoiding overshoot and collapse. There is no way of bringing into the short-term price mechanism all the information we need to guide us on a day-to-day basis and to even out this transition from growth to equilibrium without tying it very explicitly to a longterm image which has some ethical and psychological force of its own. Finally, we have to begin developing tools, projective tools, which can help us to think in more objective ways about the future consequences of those actions that we're doing today.

I remain convinced that the political and the economic system that we have in this country is one of the best starting points for this transition. It's not egoism or my background which leads me to believe that the particular mix of political choice processes, of economic allocation mechanisms, that we have here are better suited for initiating the changes necessary than those I've seen in other countries. We have a greater resource base than Europe or Japan - in some cases not only material resources but intellectual resources. The people here have always had a sort of pragmatic approach to these issues which can, I hope, lead them to recognize that some change is necessary. If, through actions at the local level and at the national level, we can really begin to dedicate ourselves to the necessity for slowing growth and begin probing the future I think that we will make that transition - not in a way which is perfectly comfortable over the short term, but one which still leaves us, 15, 20, 30 years from now, free to pursue most of our goals and to satisfy most of our domestic objectives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCelebrant of Life

April 1974

Features

-

Feature

FeatureIn sum:

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

APRIL 1964 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

FEBRUARY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureNoel Perrin Professor of English 2 pigs on a single form

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Undying

JULY 1970 By SHERMAN ADAMS '20 -

Feature

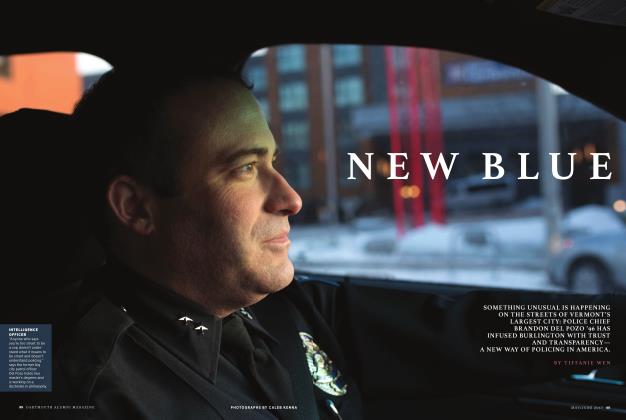

FeatureNew Blue

MAY | JUNE 2017 By TIFFANIE WEN