Since man, having assembled sounds into words, first arranged words into patterns, mindful of the music they made, those whom the Greeks called poietes, or maker, have struggled to define themselves and the verbal objects they construct.

Marianne Moore called poets "literalists of the imagination" who present for inspection "imaginary gardens with real toads in them." Robert Frost '96 observed that a poem is "a momentary stay against confusion." Archibald MacLeish maintained that "A poem should not mean/But be." Others have settled for discourses on what poetry is not.

ROBERT M. PACK '51, poet, critic, Abernethy Professor of American Literature at Middlebury College, and new director of its celebrated Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, has referred to poetry as "the transformation the imagination makes of ordinary experience." But, he adds, "a poem is never merely about something; it is something in itself. It can refer to things outside, but it has its own shape and structure; it exists in its own right."

"What I try for in my own work," he says, "is that every poem have musical structure and that I write about ordinary experiences in such a way that the usual is freshened and heightened." Of Pack's sixth volume of poetry, Nothing But Light, published last year, one reviewer wrote that he undertakes "the hard enterprise of hallowing the commonplace, of celebrating as and how we merely live."

This celebration of the commonplace recurs again and again in Pack's work, resounding - the poems of family life, rural living, and the natural, world. Although a city man born and bred, he has always felt most comfortable with country images, now the sights and sounds, the texture of Vermont, where he came to teach ten years ago from Barrard College in his native New York.

If, with his poetic confreres he resorts occasionally to the paradoxical precision of the metaphor in defining what a poem is he is quite matter-of-fact about what it should do. "What I find most interesting and most challenging in writing," he says, "is to make an affirmation, to celebrate what life is when it's good and worth living. We can't talk continually about evil and injustice without a vision of the alternative. It doesn't take a poet to tell us that these are bad times - that we all know. What is less clearly understood is what constitutes tie good life." The province of the poet, more than any other artist, he feels, is "to praise what is humanly good, to remind us that the vision is possible."

The poet is aware of the context of darkness within which joy can shine," he goes on. "He knows that celebration and lamentation go hand in hand," but the form of the poem - its concentration and brevity - permits him"to focus on joy." A note in explication of one of Pack's favorites from his own canon, "Prayer to My Father While Putting My Son to Bed," might serve as his poetic credo: "The poet adds to life in his choice and ability to praise - especially in the face of final loss and final defeat."

One thing a poem is not, Pack declares unequivocally, is "a medium for propaganda," however worthy its purpose. With Yeats, he believes "we have no gift to set a statesman right." Many a good poet, he notes, has been lost when social issue superseded music and structure

Unlike some writers who chafe under the necessity of teaching for a livelihood, viewing it as m intrusion on their real world. Pack finds his life as poet and his life as teacher blend remarkably well. Conceding the occasional conflict of time and energy, he suggests that "by and large yoi get the poems written that you have in you to write." He enjoys "guiding literature students through a poem; drawing their ittention to details - overtones, nuances of meaning, relationships between parts; helping them to respond to metaphorical language, to the sensuousness of poetic speech and the intricacies of noetic structure." And he finds special satisfaction in encouraging those gifted with the essential prerequisites - "the ability to think in metaphorical language, the patience and conviction to barn over a long period of time - to become poets themselves

After several years on the facilty at Bread Loaf, Middlebury's mountain campus, Pack looks happily forward to his second summer as director. The brainchild of Ripton, Vt., neighbor Robert Frost, the writers' conference is an intensive two weeks of classes, discussions, reading, and informal give-and-take between the first-rate professionals who teach, the promising young writers who compete for fellowships, and the instructors in creative writing who come as students.

Pack is on leave of absence this academic year, spending uninterrupted months compiling a retrospective of his own poems, composing new ones which may yet convert it into his seventh volume of verse, and writing a critical book tentatively entitled Wordsworth and the Modern tradition.

Although he ventures forth low and then - last month to Washington to deliver a lecture on Frost at the Library of Congress, occasionally to New York on brief visits - he is for the most part working where he works best, with his wife and three children in his modern house in the midst of 100 acres of Vermont farmland, surrounded by the essential ingredients of the good life he celebrates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

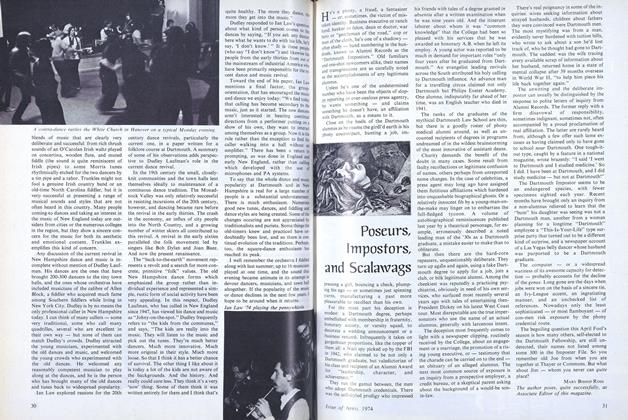

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1956 -

Feature

FeatureOut of the Amazon

MAY | JUNE 2018 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

Feature

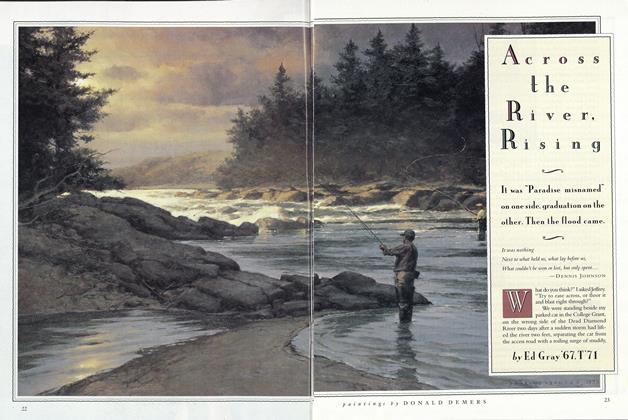

FeatureAcross the River, Rising

May 1993 By Ed Gray '67, T '71 -

COVER STORY

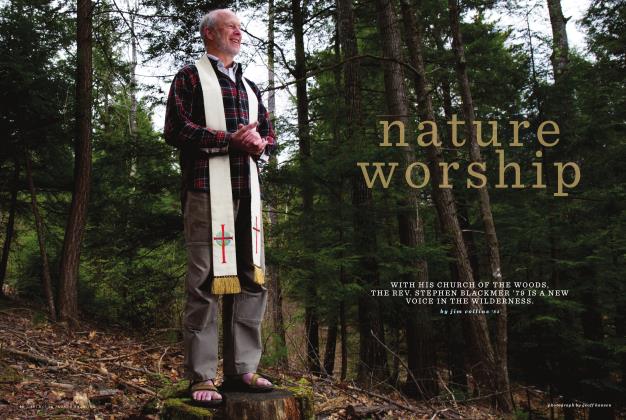

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Cover Story

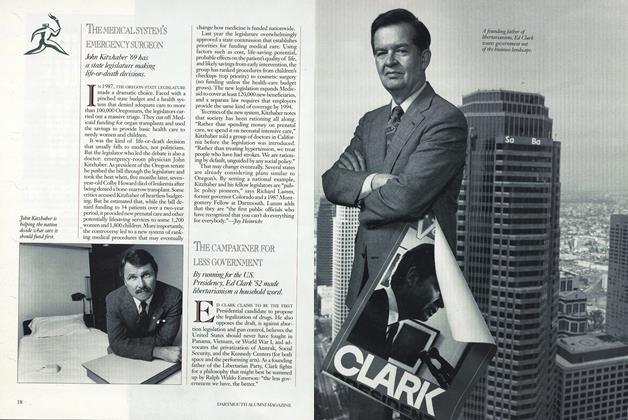

Cover StoryTHE CAMPAIGNER FOR LESS GOVERNMENT

JUNE 1990 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60