The Transmogrification of Style

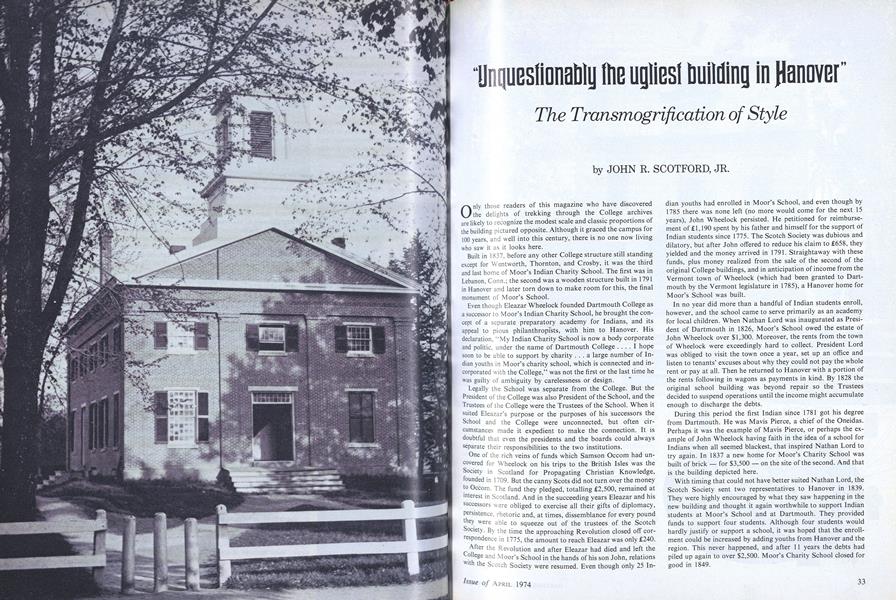

Only those readers of this magazine who have discovered the delights of trekking through the College archives are likely to recognize the modest scale and classic proportions of the building pictured opposite. Although it graced the campus for 100 years, and well into this century, there is no one now living who saw it as it looks here.

Built in 1837, before any other College structure still standing except for Wentworth, Thornton, and Crosby, it was the third and last home of Moor's Indian Charity School. The first was in Lebanon, Conn.; the second was a wooden structure built in 1791 in Hanover and later torn down to make room for this, the final monument of Moor's School.

Even though Eleazar Wheelock founded Dartmouth College as a successor to Moor's Indian Charity School, he brought the concept of a separate preparatory academy for Indians, and its appeal to pious philanthropists, with him to Hanover. His declaration, "My Indian Charity School is now a body corporate and politic, under the name of Dartmouth College.... I hope soon to be able to support by charity... a large number of Indian youths in Moor's charity school, which is connected and incorporated with the College," was not the first or the last time he was guilty of ambiguity by carelessness or design.

Legally the School was separate from the College. But the President of the College was also President of the School, and the Trustees of the College were the Trustees of the School. When it suited Eleazar's purpose or the purposes of his successors the School and the College were unconnected, but often circumstances made it expedient to make the connection. It is doubtful that even the presidents and the boards could always separate their responsibilities to the two institutions.

One of the rich veins of funds which Samson Occom had uncovered for Wheelock on his trips to the British Isles was the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, founded in 1709. But the canny Scots did not turn over the money to Occom. The fund they pledged, totalling £2,500, remained at interest in Scotland. And in the succeeding years Eleazar and his successors were obliged to exercise all their gifts of diplomacy, persistence, rhetoric and, at times, dissemblance for every pound they were able to squeeze out of the trustees of the Scotch Society. By the time the approaching Revolution closed off correspondence in 1775, the amount to reach Eleazar was only £240.

After the Revolution and after Eleazar had died and left the college and Moor's School in the hands of his son John, relations the Scotch Society were resumed. Even though only 25 Indian youths had enrolled in Moor's School, and even though by 1785 there was none left (no more would come for the next 15 years), John Wheelock persisted. He petitioned for reimbursement of £1,190 spent by his father and himself for the support of Indian students since 1775. The Scotch Society was dubious and dilatory, but after John offered to reduce his claim to £658, they yielded and the money arrived in 1791. Straightaway with these funds, plus money realized from the sale of the second of the original College buildings, and in anticipation of income from the Vermont town of Wheelock (which had been granted to Dartmouth by the Vermont legislature in 1785), a Hanover home for Moor's School was built.

In no year did more than a handful of Indian students enroll, however, and the school came to serve primarily as an academy for local children. When Nathan Lord was inaugurated as President of Dartmouth in 1826, Moor's School owed the estate of John Wheelock over $1,300. Moreover, the rents from the town of Wheelock were exceedingly hard to collect. President Lord was obliged to visit the town once a year, set up an office and listen to tenants' excuses about why they could not pay the whole rent or pay at all. Then he returned to Hanover with a portion of the rents following in wagons as payments in kind. By 1828 the original school building was beyond repair so the Trustees decided to suspend operations until the income might accumulate enough to discharge the debts.

During this period the first Indian since 1781 got his degree from Dartmouth. He was Mavis Pierce, a chief of the Oneidas. Perhaps it was the example of Mavis Pierce, or perhaps the example of John Wheelock having faith in the idea of a school for Indians when all seemed blackest, that inspired Nathan Lord to try again. In 1837 a new home for Moor's Charity School was built of brick - for $3,500 - on the site of the second. And that is the building depicted here.

With timing that could not have better suited Nathan Lord, the Scotch Society sent two representatives to Hanover in 1839. They were highly encouraged by what they saw happening in the new building and thought it again worthwhile to support Indian students at Moor's School and at Dartmouth. They provided funds to support four students. Although four students would hardly justify or support a school, it was hoped that the enrollment could be increased by adding youths from Hanover and the region. This never happened, and after 11 years the debts had piled up again to over $2,500. Moor's Charity School closed for good in 1849.

The relationship between Moor's School and Dartmouth college had been, in more than a mild way, ambiguous. With so vivid an example, the Trustees and the President might have Tied away from embarking on a similar venture. But then Abiel Chandler, Boston businessman with roots in New Hampshire, bequeathed $50,000 to the College for the "establishment of a permanent department or school of instruction in said College, in the practical and useful arts of life . . . together with bookkeeping and such other branches of knowledge as may best qualify young persons for the duties and employment of active life . . . ."The Trustees accepted the $50,000 but with lingering doubts over two restrictions in the legacy stipulating that a permanent board of visitors would see to it that Dartmouth followed the true intentions of the donor and that requirements for admission to the Chandler School were to be less rigid than those for the College.

A committee of two Trustees and President Lord prepared a plan for the new enterprise and in 1852 it opened with 19 students as the Chandler School of Science and the Arts. The new school rented the 15-year-old former home of Moor's School for $175 a year. For a while the Chandler School operated at a loss and was a drain on the College, but during the early years of Asa Smith's administration enrollment grew, economies and sharper bookkeeping practices were adopted, and the school began to show an annual surplus.

In 1871. 19 years after its founding, as evidence of the new school's healthy state, the building it occupied was extensively remodeled and enlarged. No doubt the architect who was commissioned to work out a way to increase the building's capacity and to modernize it was proud of the way he cleverly disguised the original. His ingenuity was only surpassed by his insensitivity.

To gain a full third floor, the belfry and the classic gable roof and pediment of the building were removed. Starting at a point halfway up the second floor windows, the brickwork was extended to accommodate arches between the original pilasters and a corbelled cornice. Then a heavy mansard roof and double dormers were added. It is amazing how these additions, plus the exchange of the small 20-over-20 lights in the windows for the larger panes of six-over-six and the bracketed hoods over the front and side entries, transformed a chaste and beautifully proportioned Greek Revival charmer into a mid-Victorian dowager. It now matched the other new jewels of Hanover, Culver Hall and the new bank building down the block.

Dressing up like a Newport society matron did not solve the problems of the Chandler School as far as the College was concerned. Since it was easier to get into, since its courses were felt to be inferior by the faculty of the College, and since it paid those who taught there less than the College, it was regarded as a poor relation. The students of Dartmouth were carefully categorized as either "Chandler" or "Academic" in all directories. When the College embarked upon setting up an agricultural school in 1866, it was suggested that Chandler School might be combined with the new school. Chandler, a victim of snobbery but not without its own reservoir of misplaced pride, haughtily refused to be associated with what were to be called the "dungies."

Finally in 1893, after efforts by both Presidents Smith and Bartlett to resolve the matter, William Jewett Tucker succeeded in making the marriage of Chandler and the College, after 41 years of wedded unbliss, a happy one. As so often is the case, it was more who did it than what he did. The solution, proposed by both of his predecessors but rejected because of personalities, was reached when Tucker arranged to have the term "school" discontinued in favor of the Chandler Scientific Course. By the time his service to Dartmouth was over, even this distinction had faded and the courses once taught under the aegis of Chandler School were an accepted part of the College.

During the period of Chandler School's greatest visibility, the building it occupied was known as Moor Hall. But in 1898 the college, with the aid of $28,000 from Frank Willis Daniels of the Class of 1868, bought the hall from Moor's School for $6,000 and set about making further alterations after Chandler School ceased to exist. At the time, the Aegis reported that "Moor Hall, increased as it is by the addition of considerably more hall, has had its name changed to The Chandler Building."

Perhaps the Trustees sought to mollify the Chandler board of visitors by perpetuating the name. A rose by any other name may smell as sweet, but Moor's School by another name was destined to look ever, worse. It is difficult to determine whether the changes wrought on Moor-Chandler in 1898 were an attempt to cover with cosmetics the scars of the 1871 remodeling or an effort to make it more nearly match the styles of the newer buildings on campus. For after 27 years, Victorian went out and something else came in. What it is the reader may determine from the photograph shown opposite. Perhaps the architect was stumped with the problem of adding a wing on the back which was larger than the original building. The appendage housed a large lecture hall second in capacity only to the old chapel in Darmouth Hall. To prevent the tail from wagging the dog, two porticos were added to flank the front portion and hopefully reduce the impact of the new four story addition. Now the 61-year-old dowager was a painted, turn-of-the-century frump.

The changes provided space for more classrooms and offices for the Mathematics Department and for its library, offices and drafting rooms for the Department of Graphics, and a large 200-seat lecture hall. Even after the coming of Webster Hall, the Frank W. Daniels Lecture Room was used for gatherings other than course sessions. (My father recalls a meeting of his class, 1911. in the hall being broken up by two lines of fire hoses manned by sophomores from New Hubbard, a dormitory directly behind Chandler.)

Moor's Charity School almost had a third rebirth in 1892. The income to the School had accumulated and stood at $9,000. President Bartlett proposed that it be used to build the new YMCA building which would cap the additions made to the campus during his administration. The result of his suggestion was to remind the Trustees of the existence of the Scotch Fund. Income from the endowment had also been coming in. During this period, ten Indians had been supported, most of them at Kimball Union Academy. Three of them attended Dartmouth and one, Charles A. Eastman, a Sioux, became the College's most distinguished Indian graduate up to that point. Again a Dartmouth president was inspired by a living example and suggested that Moor's School be opened again. His proposal to the Scotch Society suggested that the income from its fund be used for the general purposes of the school rather than to support individual Indian students. He felt a larger number of Indians could thus be enrolled. Time may have passed, but the Scots were no less dubious than in the early years of the century. They decided to stop the funds altogether until being satisfied that the latest grants had been used properly.

In 1915, with the assent of the Vermont Legislature (necessary because of John Wheelock's device of having half the rents from the town of Wheelock payable to Moor's School), the Supreme Court of New Hampshire allowed the funds of Moor's Charity School to be turned over to the College and the school was finished. The Society in Scotland for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge applied for relief to the Court of Sessions, the highest court in Scotland. They were granted the petition in 1922, and were permitted to divert the fund to general missionary purposes in any of the British dominions overseas.

We don't know how long the denizens of the Moor-Chandler building enjoyed their new home, but by the twenties the Mathematics Department was looking longingly for a home elsewhere. Robin Robinson recalls that as very junior members of the Math Department he and Fred Perkins were relegated to offices in the basement along with the toilets and a storeroom filled with models donated to Dartmouth by the U.S. Patent Office. They were obliged to keep all non-waterproof and/or buoyant objects on an elevated plane to prevent damage and drifting when high waters came in during the spring thaw. Their hopes soared when a large wing to be built to the south of Wilder was drawn up by Fred Larson, the College architect. But the depression dried up those dreams. No new classroom buildings were erected after Silsby (1927) until long after World War II except for the reconstruction of Dartmouth Hall after the fire of 1934. It was the rebuilding of Dartmouth Hall that provided a home for the Math Department and doomed Moor-Chandler.

Space in Moor-Chandler was not needed and not coveted. The entry of the minutes of the Dartmouth Board of Trustees for October 15, 1936, left no room for sentiment, if any existed: "Voted: That Chandler Hall be demolished." And so in its 100th year the last home of Eleazar's first dream was buried. It had survived a lot, but what really killed it as a building was fashion. If it had been left as it was built in 1837, and not gussied up to match the latest architectural fad, it probably would still be gracing the campus.

At the time it seemed that the idea of a school for Indians - a school that sometimes had students but no money, and sometimes a building but no students, sometimes all three and more often none - died with the once-lovely structure. But, after the birth of the ABC program under President Dickey and the rededication to the education of Indian students under President Kemeny, perhaps not.

"The Chandler School shared in the growth of the College as -awhole.... In 1871 the building occupied by the school... was remodeled to better serve the purposes for which itemployed. From the point of view of convenience no doubt thechange was justified, but artistically it was most unfortunate.What had been a simple, harmonious edifice became un-questionably the ugliest building in Hanover, and so it remains,despite later attempts to improve it." Leon Burr Richardson '00 in his History of Dartmouth College (1932).

"The Chandler School shared in the growth of the College as awhole.... In 1871 the building occupied by the school... was remodeled to better serve the purposes for which itemployed. From the point of view of convenience no doubt thechange was justified, but artistically it was most unfortunate.What had been a simple, harmonious edifice became un-questionably the ugliest building in Hanover, and so it remains,despite later attempts to improve it." Leon Burr Richardson '00 in his History of Dartmouth College (1932).

"It was a simple, dignified structure, along the architectural linescommon to New England academies of the period... In 1871 the structure was rebuilt, a French roof added, and it became -anarchitectural monstrosity of the type characteristic of the 1870s.In 1898 the title to the property was acquired by the College, andthe building was greatly enlarged by an extension to the rear,which added much to its unsightliness, but also to its utility....The disappearance of an ancient landmark is usually an occasionfor regret, but it would be difficult to find anyone who cherisheshsuch feelings in regard to the destruction of this structure." Sidney C. Hayward '26 in the Alumni Magazine for April 1937.

"It was a simple, dignified structure, along the architectural linescommon to New England academies of the period... In 1871 the structure was rebuilt, a French roof added, and it became -anarchitectural monstrosity of the type characteristic of the 1870s.In 1898 the title to the property was acquired by the College, andthe building was greatly enlarged by an extension to the rear,which added much to its unsightliness, but also to its utility....The disappearance of an ancient landmark is usually an occasionfor regret, but it would be difficult to find anyone who cherisheshsuch feelings in regard to the destruction of this structure." Sidney C. Hayward '26 in the Alumni Magazine for April 1937.

This view of the south side shows the large wing and porticoesadded in 1898.

John R. Scotford Jr. '38 is the College Designer. The last vestigeof Moor-Chandler was demolished during his junior year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

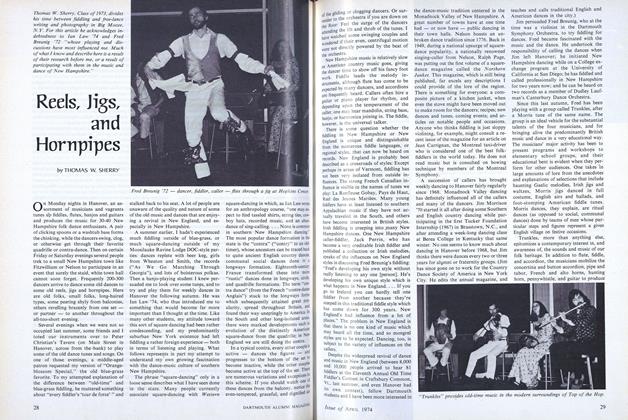

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCelebrant of Life

April 1974

Features

-

Cover Story

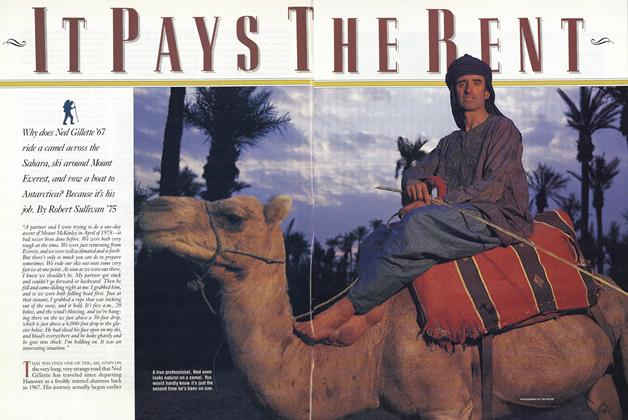

Cover StoryTHE SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE

Jan/Feb 2013 -

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

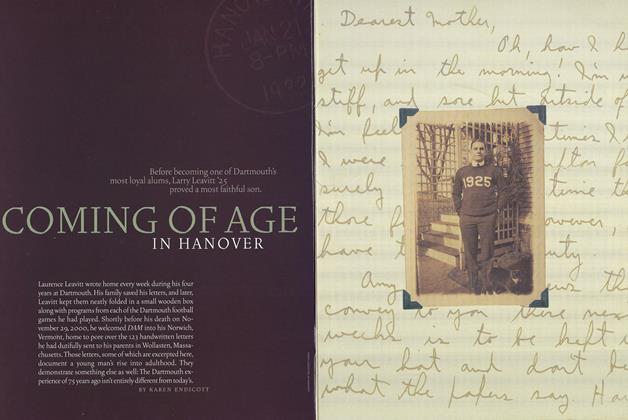

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

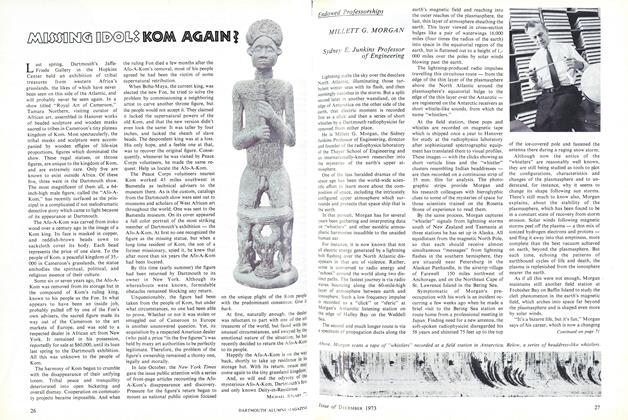

FeatureMiSSING IDOL:KOM AGAIN?

December 1973 By MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham