On Monday nights in Hanover, an assortment of musicians and vagrants tunes up fiddles, flutes, banjos and guitars and produces the music for 30-40 New Hampshire folk dance enthusiasts. A pair of clicking spoons or a washtub bass forms the chinking, while the dancers swing, clog, or otherwise get through their favorite quadrille or contra-dance. Then on certain Friday or Saturday evenings several people trek to a small New Hampshire town like Fitzwilliam or Nelson to participate in an event that surely the staid, white town hall cannot soon forget. Frequently 200-300 dancers arrive to dance some old dances to some old reels, jigs and hornpipes. Here are old folks, small folks, long-haired types, some peering shyly from balconies, others revelling brazenly from one set - or partner - to another throughout the all-too-short evening.

Several evenings when we were not so occupied last summer, some friends and I toted our instruments over to Peter Christian's Tavern (on Main Street in Hanover, across from the-bank) to play some of the old dance tunes and songs. On one of those evenings, a middle-aged patron requested my version of "Orangeblossom Special," the old blue-grass favorite. To my attempted explanation of the difference between "old-time" and blue-grass fiddling, he muttered something about "every fiddler's 'tour de force' " and stalked back to his seat. A lot of people are unaware of the quality and nature of some of the old music and dances that are enjoying a revival in New England, and especially in New Hampshire.

A summer earlier, I hadn't experienced much fiddling outside of blue-grass, or much square-dancing outside of my Moosilauke Ravine Lodge DOC-style parties: dances replete with beer keg, girls from Wheaton and Smith, the records ("As We Go Marching Through Georgia"), and lots of boisterous polkas. Then a banjo-playing student I knew persuaded me to look over some tunes, and to try and play them for weekly dances in Hanover the following autumn. He was lan Law '74, who thus introduced me to something that would become far more important than I thought at the time. Like many other students, my attitude toward this sort of square dancing had been rather condescending, and my predominantly suburban New York existence had left fiddling a rather foreign experience - both in terms of listening and playing. What follows represents in part my attempt to understand my own growing fascination with the dance-music culture of southern New Hampshire.

The phrase "square-dancing" only in a loose sense describes what I have seen done in the state. Many people currently associate square-dancing with Western square-dancing in which, as lan Law wrote for an anthropology course, "one may expect to find tassled shirts, string ties, cowboy hats, recorded music, and an abundance of sing-calling.... None is common in southern New Hampshire dancing. The most popular dance formation in the state is the "contra" ("contry" to an oldtimer), whose ancestors can be traced back to quite ancient English country dances communal social dances done in a longways formation. Eighteenth-century France transformed these into more "rustic" dances done in longways, circle, and quadrille formations. The term "contra dance" (from the French "contra-danse Anglais") stuck to the longways forms which subsequently attained great popularity, spread throughout Britain, and found their way unerringly to America. In the South and other long-isolated areas there were marked developments suchm as evolution of the distinctly American square-dance from the quadrille; in New England we are still doing the contra.

In a typical contra, every other couple is active - dances the figures - and progresses to the bottom of the set to become inactive, while the other couples become active at the top of the set. There are numerous variations and exceptions to this scheme. If you should watch one of these dances from the balcony, notice the even-tempered, graceful, and dignified an of the gliding or clogging dancers. Or surrender to the orchestra if you are down on the floor: Feel the surge of the dancers attending the lilt and throb of the tunes. I have watched some swinging couples and wondered if their even' centrifugal motion were not directly powered by the beat of the orchestra.

New Hampshire music is relatively slow as American country music goes, giving the dancer time to show off his fancy foot work. Fiddle leads the melody instruments, although flute has come to be expected by many dancers, and accordions are frequently heard. Callers often hire a Guitar or piano player for rhythm, and depending upon the temperament of the caller, one may hear mandolin, string bass, banjo', or harmonica joining in. The fiddle, however, is the universal talker.

There is some question whether the fiddling in New Hampshire or New England is unique and distinguishable from the numerous fiddle languages, or regional styles, that can now be heard on records. New England is probably best described as a crossroads of styles; Except perhaps in areas of Vermont, fiddling has not been very isolated from outside influences. The strong French Canadian influence is visible in the names of tunes we play: La Ronfleuse Gobay, Pays de Haut, Reel des Jeunes Mariées. Many young fiddlers have at least listened to southern Appalachian music if they have not actually traveled in the South, and others have become interested in British styles. Irish fiddling is creeping into many New Hampshire dances. One New Hampshire caller-fiddler, Jack Perrin, who has become a very creditable Irish fiddler and published a collection or Irish melodies, speaks of the influences on New England styles in discussing Fred Breunig's fiddling: "Fred's developing his own style without really listening to any one [person]. He's developing his own unique style which is what happens in New England. ... If you go to Ireland you can hardly tell one tiddler from another because they're steeped in this traditional fiddle style which has come down for 300 years. New England's had influence from a lot of places." The problem in New England is that there is no one kind of music which may heard all the time, and so mongrel styles are to be expected. Dancing, too, is subject to the variety of influences on the callers.

Despite the widespread revival of dance and music in New England (between 8,000 and 10,000 people arrived to hear 81 fiddlers at the Eleventh Annual Old Time fiddler's Contest in Craftsbury Common, Vt., last summer, and even Hanover had uts own contest), fellow Dartmouth students and I have been more interested in the dance-music tradition centered in the Monadnock Valley of New Hampshire. A great number of towns have at one time had - or now have - public dancing in their town halls. Nelson boasts an unbroken dance tradition since 1776. Back in 1949, during a national upsurge of squaredance popularity, a nationally renowned singing-caller from Nelson, Ralph Page, was putting out the first volume of a squaredance magazine called the NorthernJunket. This magazine, which is still being published, far excels any descriptions I could provide of the lore of the region. There is something for everyone: a composite picture of a kitchen junket, when even the stove might have been moved out to make room for the dancers; recipes; new dances and tunes; coming events; and articles on notable people and occasions. Anyone who thinks fiddling is just sloppy violining, for example, might consult a recent issue of the magazine for an article on Jean Carrignan, the Montreal taxi-driver who is considered one of the best folkfiddlers in the world today. He does not read music but is consulted on bowing technique by members of the Montreal Symphony.

A succession of callers has brought weekly dancing to Hanover fairly regularly since 1968. Monadnock Valley dancing has definitely influenced all of the callers and many of the dancers. Jim Morrison '7O started it all after doing some Southern and English country dancing while participating in the first Tucker Foundation Internship (1967) in Brasstown, N.C., and after attending a week-long dancing class at Berea College in Kentucky that same winter. No one seems to know much about dancing in Hanover before 1968, but Jim thinks there were dances every two or three years for alumni or fraternity groups. (Jim has since gone on to work for the Country Dance Society of America in New York City. He edits the annual magazine, and teaches and calls traditional English and American dances in the city.)

Jim persuaded Fred Breunig, who at the time was a violinist in the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra, to try fiddling for dances. Fred became fascinated with the music and the dance. He undertook the responsibility of calling the dances when Jim left Hanover; he initiated New Hampshire dancing while on a College exchange program at the University of California at San Diego; he has fiddled and called professionally in New Hampshire for two years now; and he can be heard on two records as a member of Dudley Laufman's Canterbury Dance Orchestra.

Since this last autumn, Fred has been playing with a group called Trunkles, after a Morris tune of the same name. The group is an ideal vehicle for the substantial talents of the four musicians, and for bringing alive the predominantly British music and dance in a very educational way. The musicians' major activity has been to present programs and workshops to elementary school groups, and their educational bent is evident when they perform for other audiences. One takes in large amounts of lore from the anecdotes and explanations of selections that include haunting Gaelic melodies, Irish jigs and waltzes, Morris jigs danced in full costume, English airs and ballads, and foot-stomping American fiddle tunes. Morris dances, they explain, are ritual dances (as opposed to social, communal dances) done by teams of men whose particular steps and figures represent a given English village on festive occasions.

Trunkles, more than anything else, epitomizes a contemporary interest in, and awareness of, the sounds and music of our folk heritage. In addition to flute, fiddle, and accordion, the musicians mobilize the concertina and button accordion, pipe and tabor, French and alto horns, hunting horn, pennywhistle, and guitar to produce blends of music that are clearly very deliberate and successful: from rich thrush sounds of an O'Carolan Irish waltz played on concertina, wooden flute, and muted fiddle (the sound is quite reminiscent of Irish pipes) to some Morris tunes rhythmically etched for the two dancers by a tin pipe and a tabor. Trunkles might not fool a genuine Irish country band or an old-time North Carolina fiddler, but it is very- successful at presenting' a range of musical sounds and styles that are not often heard in this country. Many people coming-to dances and taking an interest in the music of New England today are outsiders from cities or the numerous colleges in the region, but they show a sincere concern for the music for both its aesthetic and emotional content. Trunkles ex- emplifies this kind of concern.

Any discussion of the current revival in New Hampshire dance and music is in- complete without mention of Dudley Lauf- man. His dances are the ones that have brought 200-300 dancers to the tiny town halls, and the ones whose orchestras have included musicians of the calibre of Allen Block, a fiddler who acquired much fame among Southern fiddlers while living in New York City. Dudley is by no means the only professional caller in New Hampshire today. I can think of many callers - some very traditional, some who call many quadrilles, several who are excellent in their own way - but none of them can match Dudley's crowds. Dudley attracted the young musicians, experimented with the old dances and music, and welcomed the young crowds who experimented with the old dances. He welcomed any reasonably competent musician to play along at the dances, and he is the person who has brought many of the old dances and tunes back to widespread popularity.

Lan Law explored reasons for the 20th century dance revivals, particularly the current one, in a paper written for a folklore course at Dartmouth. A summary of some of his observations adds perspec- tive to Dudley Laufman's role in the current dance revival.

In the 19th century the small, closely- knit communities and the town halls lent themselves ideally to maintenance of a continuous dance tradition. The Monadnock Valley was only relatively successful in resisting incursions of the 20th century, however, and dancing became rare before the revival in the early thirties. The crash in the economy, an influx of city people into the North Country, and a growing number of winter skiers all contributed to this revival. A revival in the early sixties paralleled the folk movement led by singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. And now the present renaissance.

The "back-to-the-earth" movement represents a revolt and a search for more concrete, primitive "folk" values. The old New Hampshire dance forms which emphasized the group rather than individual experience and represented a simple, rustic form of social activity have been very appealing. In this respect, Dudley Laufman, who has called in New England since 1947, has viewed his dance and music as "Johny-on-the-spot." Dudley frequently refers to "the kids from the communes," and says, "The kids are really into the music. They will listen to the music and pick out the tunes. They're much better dancers. Much more innovative. Much more original in their style. Much more loose. So that I think it has a better chance of survival. The other thing I like about it is today a lot of the kids are not aware of the backgrounds. And the history. And really could care less. They think it's a very 'now' thing. Some of them think it was written entirely for them and I think that's quite healthy. The more they dance, the more they get into the music."

Dudley responded to lan Law's question about what kind of person comes to the dances by saying, "If you ask any dancehere what he wants to do with his life, he'll say, 'I don't know.' " It is these people (who say "I don't know") and likewise the people from the early thirties from out of the mainstream of industrial America who have been primarily responsible for the recent dance and music revival.

Toward the end of his paper, lan Law mentions a final factor, the grouporientation, that has encouraged the music and dance we enjoy today: "We find today that calling has become secondary to the music, just as it started. The new dancers aren't interested in hearing continual directions from a performer putting on a show of his own, they want to interact among themselves as a group. Now it is the rule rather than the exception to find the caller walking into a hall without an amplifier." There has been a return to prompting, as was done in England and early New England, rather than calling which developed with the use of microphones and PA systems.

To say that the whole dance and music popularity at Dartmouth and in New Hampshire is real for a large number of people is a substantial understatement. There is much enthusiasm. Numerous good new tunes, dances, and fiddling and dance styles are being created. Some of the changes occuring are not appreciated by traditionalists and purists. Some things the old-timers knew and practiced have undoubtedly been lost, and so there is continual evolution of the traditions. Perhaps, too, the square-dance enthusiasm has reached its peak.

I well remember the orchestra I fiddled along with last summer; up to 16 musicians played at one time, and the sound that evening became animate in its attempt to devour dancers, musicians, and town hall altogether. If the popularity of the music or dance declines in the next few years. I hope to be around when it returns.

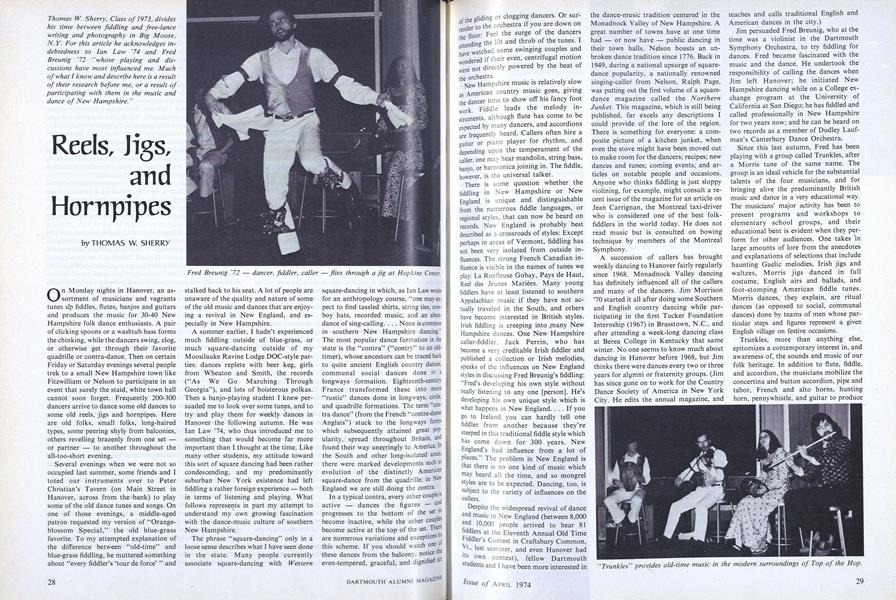

Fred Breunig '72 - dancer, fiddler, caller flies through a jig at Hopkins Center

"Trunkles" provides old-time music in the modern surroundings of Top of the Hop.

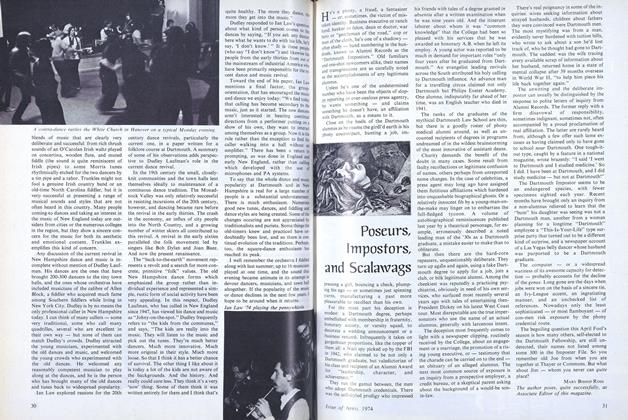

A contra-dance rattles the White Church in Hanover on a typical Monday evening.

Lan Law '74 playing the penny whistle.

Thomas W. Sherry, Class of 1973, divideshis time between fiddling and free-lancewriting and photography in Big Moose,N. Y. For this article he acknowledges in-debtedness to Ian Law '74 and FredBreunig '72 "whose playing and dis-cussions have most influenced me. Muchof what I know and describe here is a resultof their research before me, or a result ofparticipating with them in the music anddance of New Hampshire."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCelebrant of Life

April 1974

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBE Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

Feature1. Academic achievement

December 1987 -

Feature

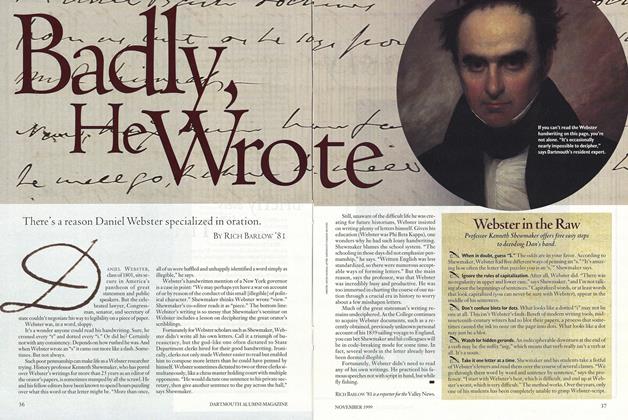

FeatureWebster in the Raw

NOVEMBER 1999 -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureFIFTY YEARS OF THE DOC

February 1960 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56