Edited by Herbert L.Marx Jr. '43. New York: The H.W. WilsonCo., 1973. 188 pp. $4.50.

If one reads The American Indian: A RisingEthnic Force in order to find out once and for all who Native Americans are, what "they" want or where "they" are headed, one will be frustrated upon the book's completion and probably more confused than when one began. Certainly many of the articles in this very contemporary anthology deal with these issues, but quite predictably no two of them reach precisely the same conclusions.

And this is as it should be. It is debatable whether the many cultures of present-day Native America ever have or do now constitute an "ethnic force"; rather, what emerges from Marx's collection is sometimes a confusing and contradictory but to a certain degree realistic picture of the multiplicity of culture, direction, past, and future of Native American people.

Some of the best selections underline this pluralism. Carl Degler's Commentary article "Indians and other Americans" neatly recounts the logical rationale for the persistence of Native American diversity in a melting-pot society, and the excerpt from Murray Wax's IndianAmericans examines the ethno-historical bases for disunity.

Whether by accident or design, Marx has also included examples of the two unquenchable stereotypic extremes, from the know-nothing racism of John Greenway's "A Contrary View" to the lump-in-the-throat noble savagery of Earl Shorris' "Indian Love Call." These two articles, in their smug and ill-informed way most interesting, illustrate one of the real "plights" of the contemporary Native American: the never-ending attempt by some non-Indians to define him according to their own symbol systems.

The truth of the matter, of course, is that historically the native inhabitants of the Americas were at least as ethnically diverse as the residents of Europe or Asia and that any attempt to understand them as a single group is folly. Native Americans today are like the survivors of an earthquake: circumstantially they share many of the same problems, but each group must cope with a changed environment primarily in terms of their own culture's orientation. There is perhaps as little harmony in the Indian world as in the non-Indian.

Appropriately the overriding concern of most Native Americans in the past 400 years had been simple survival. To the consternation of many, they have succeeded. Like those of other residents of the planet, the many cultures of Native American people have changed and adapted over the years. They have borrowed freely from other world societies, just as other societies have borrowed from them. (Imagine an Ireland without the Peruvian potato, an Italy without the Mexican tomato, or a Cheyenne without a Spanish horse.) The accomplishment from the native perspective, however, is the ability to borrow without disappearing, to preserve cultural integrity in a world where the possibility of cultural isolation does not exist.

The American Indian: A Rising Ethnic Force despite the inclusion of a few potent inaccuracies, (e.g. the depiction of the Menominee as content to be terminated), is valuable as a reference anthology. Its articles contain some of the better analyses of the contemporary major questions.

Mr. Dorris is chairman of the Native AmericanStudies Program at Dartmouth and an instructorin the Department of Anthropology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Books

-

Books

BooksA History of English Literature

March 1918 -

Books

BooksThe Underside

October 1980 By A. Roger Ekirch '72 -

Books

BooksCASES AND MATERIALS ON FEDERAL TAXATION

April 1950 By LLOYD P. RICE -

Books

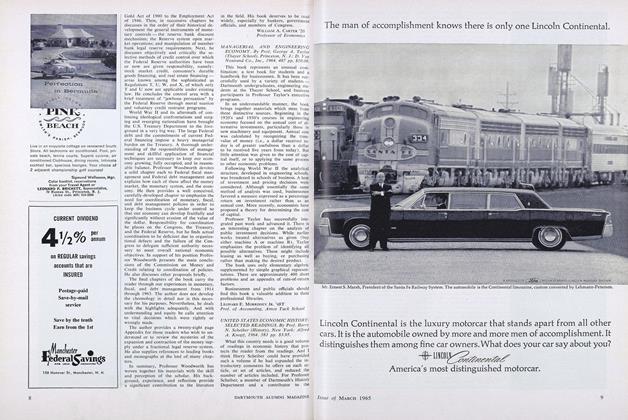

BooksUNITED STATES ECONOMIC HISTORY: SELECTED READINGS.

MARCH 1965 By RICHARD S. BOWER -

Books

BooksLines for a Tomb-Stone

MAY 1932 By William Kimball flaccus -

Books

BooksTHE EVOLUTION OF A MEDICAL CENTER: A HISTORY OF MEDICINE AT DUKE UNIVERSITY TO 1941.

NOVEMBER 1972 By WILLIAM L. WILSON '34