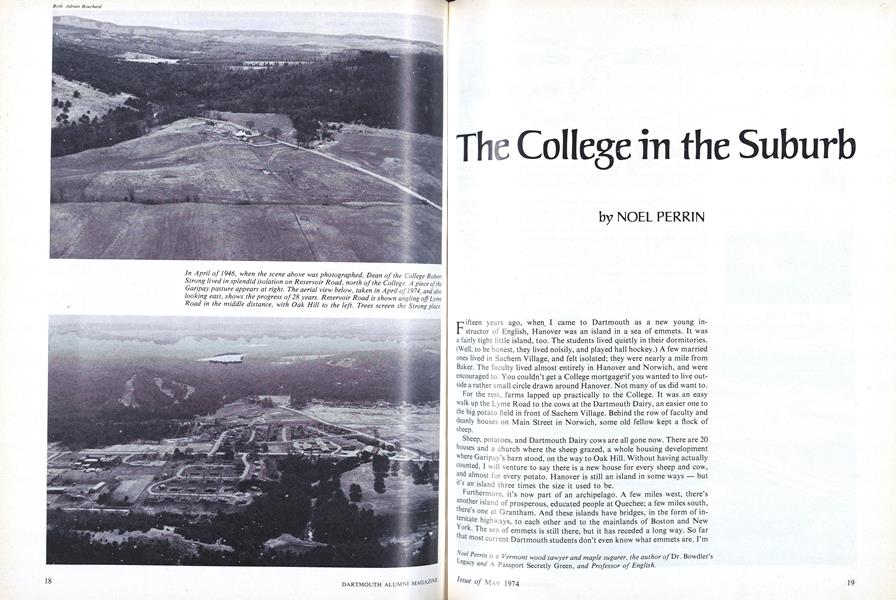

Fifteen years ago, when I came to Dartmouth as a new young instructor of English, Hanover was an island in a sea of emmets. It was a fairly tight little island, too. The students lived quietly in their dormitories. (Well, to be honest, they lived noisily, and played hall hockey.) A few married Ones lived in Sachem Village, and felt isolated; they were nearly a mile from Baker. The faculty lived almost entirely in Hanover and Norwich, and were encouraged to. You couldn't get a College mortgageif you wanted to live outride a rather small circle drawn around Hanover. Not many of us did want to.

For the rest, farms lapped up practically to the College. It was an easy walk up the Lyme Road to the cows at the Dartmouth Dairy, an easier one to the big potato field in front of Sachem Village. Behind the row of faculty and deanly houses on Main Street in Norwich, some old fellow kept a flock of sheep.

Sheep, potatoes, and Dartmouth Dairy cows are all gone now. There are 20 mouses and a church where the sheep grazed, a whole housing development where Garipay's barn stood, on the way to Oak Hill. Without having actually counted. I will venture to say there is a new house for every sheep and cow, and almost for every potato. Hanover is still an island in some ways - but it's an island three times the size it used to be.

Furthermore, it's now part of an archipelago. A few miles west, there's another island of prosperous, educated people at Quechee; a few miles south, there's one at Grantham. And these islands have bridges, in the form of interstate highways, to each other and to the mainlands of Boston and New York. The sea of emmets is still there, but it has receded a long way. So far that most current Dartmouth students don't even know what emmets are. I'm sure; I checked with my freshman class this morning. Five out of' 19 Coild define an emmet. Zero were conscious of having met one.

The figures would doubtless be higher among upperclassmen, a considerable number of whom, these days, live in ex-farmhouses in Enfield or converted barns in Etna. But even there, their neighbors are likely to be new instructors of physics, or retired lawyers from Toledo, class of' 32. Anything but New Hampshire countrymen. The woods are full, so to speak, of suburbanites.

This influx of prosperous, educated people has had an overwhelming effect on land prices, as any reader of the real estate ads in the Alumni Magazine is aware. A country house (a grand one, to be sure) and 350 acres were offered at half a million dollars, not long ago. The land alone would probably have brought close to a quarter of a million. Ten years ago, one might have got it for $20,000. In Hanover itself, prices run much higher. Building lots - carved from the forested slopes of Balch Hill, or from the farmland north of town run around $l0,000. That's why condominiums, such as the new Levitt development off Wheelock Street, are so popular. Come into the center, come onto Main Street, and you will find land currently assessed at $8 a square foot, or roughly $320,000 an acre. That assessment could hold up its head in Bronxville or Shaker Heights.

With land prices like these, farming is naturally not very profitable. The taxes on a farm or a piece of woodland within 30 miles of Dartmouth are in danger of exceeding the income one could make by dairying, or logging, or anything else one could do that arises from the land itself. And the result is that even off the islands, the native world is in retreat. Rural New Hampshire and Vermont are right now in the process of becoming suburban New Hampshire and Vermont. There may still be wolf winds, but they'll blow over a landscape full of cocker spaniels on leashes.

You think I exaggerate? I can give statistics. Take my own town of Thet-ford, Vt. It's the one just north of Norwich, and across the river from Lyme For the last 200 years Thetford has been a farming community, with touches of light (very light) industry in the five villages. For example, there used to be a small factory that produced ax handles in Thetford Center, and there is still one that makes blanks for chair legs in Post Mills.

When I left the Dartmouth island and bought a farm in Thetford in 1963, I was moving into true, rural New England. My next neighbor on one side kept Holsteins; the one on the other side drove a logging truck. All but the main roads were unpaved. The population had been stable at about a thousand people for many years.

Now, 11 years later, there are nine farms left in town. Even if you throw in the semi-farms like my own, the figure comes to about 20. Meanwhile, the population has just about doubled. Real, working farmers now own just over ten per cent of the land. Who owns the rest? All sorts of people, including a great many stubborn locals, and two or three sharp investors in Boston. Most of it, though, is owned by middle-class newcomers.

A very bright young anthropologist named Jane Korey has just done a study of the land and people of Thetford - in fact, she is going to get her Ph.D. at Brandeis with this study as part of her field work. Mrs. Korey divided the present inhabitants of Thetford into two classes: "natives" and "elite," the dividing line being educational. Anyone who didn't go past high school she called a native, anyone who did she called a member of the elife. At this moment the town is about two-thirds native, one-third elite.

Obviously Mrs. Korey's two classes are not quite the same as the old-timers in town versus the newcomers. There are people born in town, in-eluding at least one logger, who have been to college, and there are some newly arrived high-school dropouts from big cities. But there aren't many. They can't afford to buy land here. Her categories work pretty well

Of the "natives" in her study-sample, it turns out that 90 per cent first went to school somewhere in rural Vermont, that 80 per cent were raised on farms, that 16 per cent have ever lived in a city. Of the "elite," on the other hand, zero per cent first went to school in rural Vermont, 40 per cent have been to private schools, 100 per cent have lived in cities. Their numbers are increasing fast. Which is why the first bank in Thetford's history opened a couple of months ago. And why the town planning commission has as its top priority the writing of a subdivision ordinance. And why this year's town report laments that a master plan made eight years ago is already obsolete "It could not anticipate the spectacular growth that Thetford has seen in the last few years, mainly due to the interstate." Spectacular growth means the arrival of a disease which in the East is called New Jerseyitis, and which in the West I am told is called Californication.

This isn't to say that the arrival of so many urban refugees is all bad, even from the point of view of wolf winds and of the preservation of rural life. Particularly when they stay on the islands, there is quite a lot of good. The town of Grantham, N.H., makes a striking example. About a sixth of the total area of Grantham is now one enormous development, called Eastman Pond. Dartmouth College owns a third of it. The New Hampshire Society for the Preser-vation of Forests owns a sixth, and a New Hampshire bank and insurance company own the other half.

These four on the whole benevolent developers first bought 3,500 acres surrounding a fair-sized lake. Then they laid out a golf course, ski slopes, tennis courts, hiking trails. They started a good restaurant, made plans for a community sugar house (so that the people who live at Eastman can produce maple syrup), and so forth. Finally, they staked out 1,647 building sites, which average about an acre each. So far they've sold not quite 700 of them. The last time anyone counted, which was last fall, 143 of these buyers turned out to be Dartmouth alumni. There is a41-year span, from the class of '28 to the class of '69. At the moment, about 75 lot owners have built houses at Eastman, and new ones will be going up for the next quarter century at the rate of 50 or 60 a year.

The building lots at Eastman are expensive - $7,500 to $ 17,000 - and the houses are even more expensive. There are also quite a lot of public buildings, including a cocktail barn. The result is a tremendous new source of tax revenue for the town of Grantham, without much rise in expense. Eastman maintains its own roads, and the number of new school children is negligible so far. Most of the younger families on the island have another house somewhere else; and of those who don't, about 40 per cent, by Korey's Law, will send their kids to private school.

The effects of Eastman have already shown up in the town budget. When the 400 natives who live in Grantham were collecting taxes just on their own houses and property, the tax rate was $3.40, and the town budget was $17,000. That was two years ago. Last year the tax rate dropped to $1.68, but the town budget nevertheless doubled. This year it will double again, as the town happily buys new road machinery and puts aside $20,000 toward a new town office building. Meanwhile, the school budget has gone up a mere eight per cent, and the school tax rate has plummeted.

None of this benefits the farmers of Grantham, because there aren't any farmers in Grantham. New Hampshire lost its farms a full generation ahead of Vermont. (Hanover and the other towns along the Connecticut River are exceptions, because the soil is so much better.) But there are plenty of New Hampshire countrymen in Grantham, some of them with a cow or two, and many with a woodlot. It benefits them very much. Since the town collects its taxes almost entirely on improved land and buildings, and has raised the assessment of woodland not at all, a Granthamite with a hundred acres of woods is paying much lower taxes than he did two years ago. In Grantham the island has been good for the sea.

In 20 years it may look different, of course. By then, there will be twelve hundred or so houses at Eastman, plus a 400-unit cluster development. East-manites will be a large majority in town, and will be controlling the government. There will be a shopping center on what is currently someone's woodlot; there will be traffic lights and banks and probably a drive-in movie. All this will diminish the rural character of the town. Furthermore, land will have been for many years too expensive to buy for country uses. Only the rich will be able to afford more than a few acres. In fact, this is really the case right now. This year's town budget sets aside $10,000 to buy a piece of land maybe five or ten acres for the town to put the new town office on, and eventually a town garage. The selectmen don't expect the sum to be large enough for more than a down payment. "I don't know if land is worth more than it was ten years ago," one of them observed this spring, "but they sure are charging more."

All the same, some benefits will still flow from the island. It will still probably be the case, 20 years from now, that Grantham natives will be comfortably paying the taxes on the land they already own, doing a little logging, some of them keeping a cow or two. I wish I were sure the same would be true in Thetford.

If this is the future of rural Grantham, what about Hanover, which already has traffic lights and banks (the second one arrived in 1973) and movies? In 20 years will there be apartment houses where DOC cabins now stand, a Holiday Inn on Moose Mountain, a branch of E.J. Korvette next to the Bema? It s certainly possible. Before those wonderful people who brought us Levit-town have even finished their present condominium development, they have announced plans for a much larger development on Balch Hill. The nearest Holiday Inn is no more than five miles from the Hanover border, and Howard Johnsons is hot behind.

But I am betting that Hanover is not going to go that way. At least for the moment, the town has blocked the second Levitt development. A large group of residents is busy trying to change the zoning on upper Balch Hill in case the town block fails. Still another group is trying to get a two-year freeze on development altogether, while Hanover works out a whole new code for land use.

If that code is written right - and right means so that land is taxed according to use, and not according to what it's worth to any company that intends to put up apartment houses wherever it can find a flat cow pasture - then there is hope. Then I am betting the sea will lap back up to the Hanover island, and it will remain possible to bicycle if not to walk out to cows and sheep and potato fields. Then Dartmouth will keep its unique setting.

The turn-of-the-century photograph above, which has all the appearances of a watercolorby the late Paul Sample, shows the original Ledyard Bridge, the tiny river bank hamlet ofLewiston, and the hills of Norwich beyond. And today? Well, the old covered bridge wasdemolished in 1934, Lewiston went the way of many river hamlets, and the approach toarchipelagic Hanover (below) is one big undulating exit ramp for interstate 91.

Noel Perrin is a Vermont wood sawyer and maple sugarer, the author of Dr. Bowdler's Legacy and A Passport Secretly Green, and Professor of English.

NOEL PERRIN

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth, Dartmouth, Doing Right

OCTOBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

NOVEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Cubicle of One's Own

JUNE 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleFour Aces

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureNomss de Blitz

OCTOBER 1998 By NOEL PERRIN

Features

-

Feature

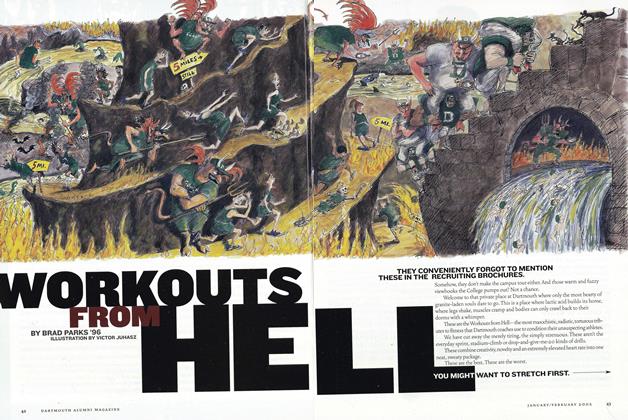

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

FEATURE

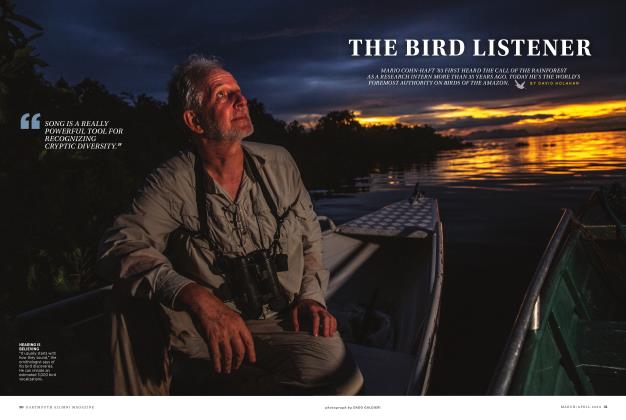

FEATUREThe Bird Listener

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Feature

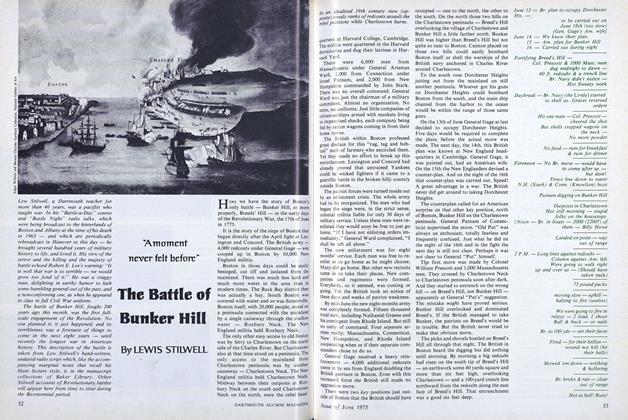

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2012 By Llewelynn Fletcher ’99 -

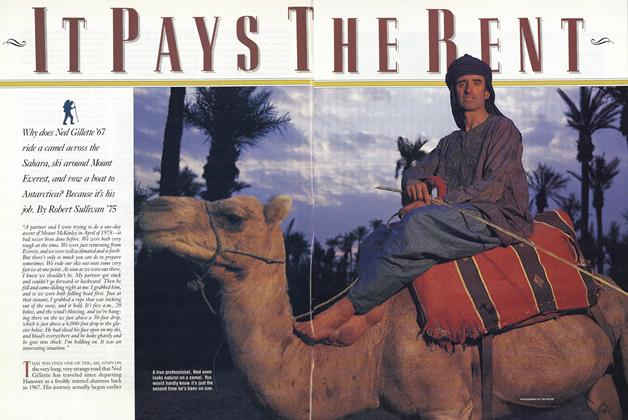

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

NOVEMBER 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70