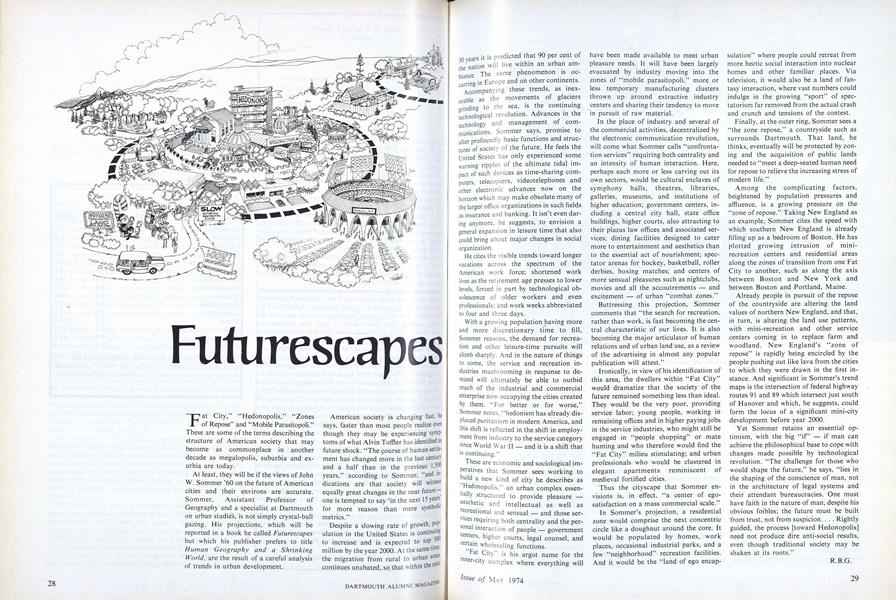

"Fat City," "Hedonopolis," "Zones of Repose" and "Mobile Parasitopoli." These are some of the terms describing the structure of American society that may become as commonplace in another decade as megalopolis, suburbia and exurbia are today.

At least, they will be if the views of John W. Sommer '6O on the future of American cities and their environs are accurate. Sommer, Assistant Professor of Geography and a specialist at Dartmouth on urban studies, is not simply crystal-ball gazing. His projections, which will be reported in a book he called Futurescapes but which his publisher prefers to title Human Geography and a ShrinkingWorld, are the result of a careful analysis of trends in urban development.

American society is changing fast. says, faster than most people realize eve' though they may be experiencing symp- toms of what Alvin Toffler has identified as future shock. "The course of human settlement has changed more in the last century and a half than in the previous 1.50 years," according to Sommer, "and indications are that society will witness equally great changes in the near future - one is tempted to say 'in the next 15 year? for more reason than mere symbol metrics."

Despite a slowing rate of growth. Population in the United States is continuing to increase and is expected to top 300 million by the year 2000. At the same time, the migration from rural to urban areas continues unabated, so that within the next 30 years it is predicted that 90 per cent of the nation will live within an urban ambiance. The same phenomenon is occurring in Europe and on other continents.

Accompanying these trends, as inexbrable as the movements of glaciers grinding to the sea, is the continuing technological revolution. Advances in the technology and management of communications, Sommer says, promise to alter profoundly basic functions and structures of society of the future. He feels the United States has only experienced some warning ripples of the ultimate tidal impact of such devices as time-sharing computers, telecopiers, videotelephones and other electronic advances now on the horizon which may make obsolete many of the larger office organizations in such fields as insurance and banking. It isn't even daring anymore, he suggests, to envision a general expansion in leisure time that also could bring about major changes in social organization.

He cites the visible trends toward longer vacations across the spectrum of the American work force; shortened work lives as the retirement age presses to lower levels, forced in part by technological obsolescence of older workers and even professionals; and work weeks abbreviated to four and three days.

With a growing population having more and more discretionary time to fill, Sommer reasons, the demand for recreation and other leisure-time pursuits will climb sharply. And in the nature of things to come, the service and recreation industries mushrooming in response to demand will ultimately be able to outbid much of the industrial and commercial enterprise now occupying the cities created by them. "For better or for worse," Sommer notes, "hedonism has already displaced puritanism in modern America, and this shift is reflected in the shift in employment from industry to the service category since World War II - and it is a shift that is continuing."

These are economic and sociological imperatives that Sommer sees working to build a new kind of city he describes as "Hedonopolis," an urban complex essen-tially structured to provide pleasure - esthetic and intellectual as well as and sensual - and those services requiring both centrality and the personal interaction of people - government centers, higher courts, legal counsel, and certain wholesaling functions.

"Fat City is his argot name for the inner-city complex where everything will have been made available to meet urban pleasure needs. It will have been largely evacuated by industry moving into the zones of "mobile parasitopoli," more or less temporary manufacturing clusters thrown up around extractive industry centers and sharing their tendency to move in pursuit of raw material.

In the place of industry and several of the commercial activities, decentralized by the electronic communication revolution, will come what Sommer calls "confrontation services" requiring both centrality and an intensity of human interaction. Here, perhaps each more or less carving out its own sectors, would be cultural enclaves of symphony halls, theatres, libraries, galleries, museums, and institutions of higher education; government centers, including a central city hall, state office buildings, higher courts, also attracting to their plazas law offices and associated services; dining facilities designed to cater more to entertainment and aesthetics than to the essential act of nourishment; spectator arenas for hockey, basketball, roller derbies, boxing matches; and centers of more sensual pleasures such as nightclubs, movies and all the accoutrements - and excitement - of urban "combat zones."

Buttressing this projection, Sommer comments that "the search for recreation, rather than work, is fast becoming the central characteristic of our lives. It is also becoming the major articulator of human relations and of urban land use, as a review of the advertising in almost any popular publication will attest."

Ironically, in view of his identification of this area, the dwellers within "Fat City" would dramatize that the society of the future remained something less than ideal. They would be the very poor, providing service labor; young people, working in remaining offices and in higher paying jobs in the service industries, who might still be engaged in "people shopping" or mate hunting and who therefore would find the "Fat City" milieu stimulating; and urban professionals who would be clustered in elegant apartments reminiscent of medieval fortified cities.

Thus the cityscape that Sommer envisions is, in effect, "a center of ego-satisfaction on a mass commercial scale."

In Sommer's projection, a residential zone would comprise the next concentric circle like a doughnut around the core. It would be populated by homes, work places, occasional industrial parks, and a few "neighborhood" recreation facilities. And it would be the "land of ego encapsulation" where people could retreat from more hectic social interaction into nuclear homes and other familiar places. Via television, it would also be a land of fantasy interaction, where vast numbers could indulge in the growing "sport" of spectatorism far removed from the actual crash and crunch and tensions of the contest.

Finally, at the outer ring, Sommer sees a "the zone repose," a countryside such as surrounds Dartmouth. That land, he thinks, eventually will be protected by zoning and the acquisition of public lands needed to "meet a deep-seated human need for repose to relieve the increasing stress of modern life."

Among the complicating factors, heightened by population pressures and affluence, is a growing pressure on the "zone of repose." Taking New England as an example, Sommer cites the speed with which southern New England is already filling up as a bedroom of Boston. He has plotted growing intrusion of minirecreation centers and residential areas along the zones of transition from one Fat City to another, such as along the axis between Boston and New York and between Boston and Portland, Maine.

Already people in pursuit of the repose of the countryside are altering the land values of northern New England, and that, in turn, is altering the land use patterns, with mini-recreation and other service centers coming in to replace farm and woodland. New England's "zone of repose" is rapidly being encircled by the people pushing out like lava from the cities to which they were drawn in the first instance. And significant in Sommer's trend maps is the intersection of federal highway routes 91 and 89 which intersect just south of Hanover and which, he suggests, could form the locus of a significant mini-city development before year 2000.

Yet Sommer retains an essential optimism, with the big "if' - if man can achieve the philosophical base to cope with changes made possible by technological revolution. "The challenge for those who would shape the future," he says, "lies in the shaping of the conscience of man, not in the architecture of legal systems and their attendant bureaucracies. One must have faith in the nature of man, despite his obvious foibles; the future must be built from trust, not from suspicion.... Rightly guided, the process [toward Hedonopolis] need not produce dire anti-social results, even though traditional society may be shaken at its roots."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

R.B.G.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

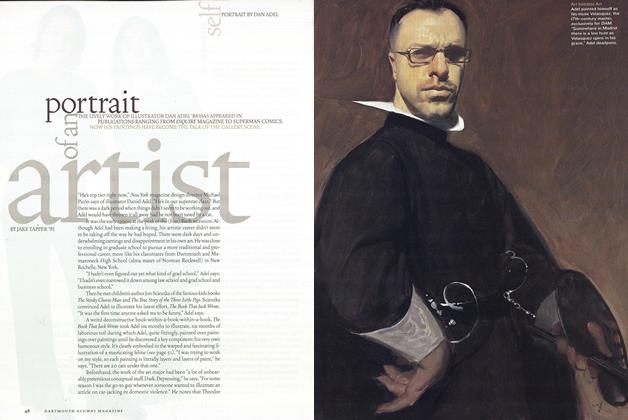

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

Mar/Apr 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureDweck & Ivey's Good Offense

JANUARY 1998 By LINDA TITLAR -

Feature

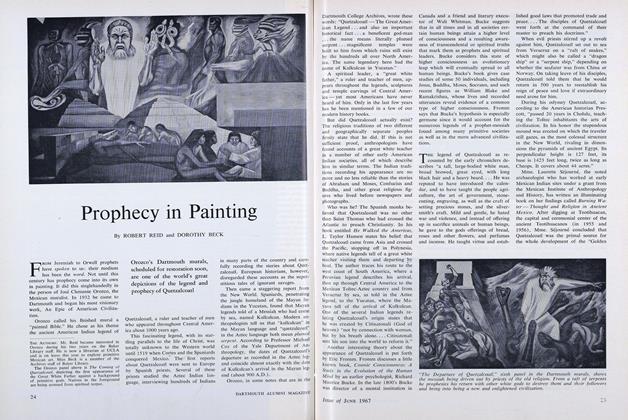

FeatureProphecy in Painting

JUNE 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1956 By WILLIAM FREDERICK BEHRENS '56