NORTHERN LIGHTS: WRITERS FROM THE UPPER VALLEY OF VERMONT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE.

June 1974 CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65NORTHERN LIGHTS: WRITERS FROM THE UPPER VALLEY OF VERMONT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE. CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65 June 1974

Young Jr. lAssistant Professor of RussianLanguage and Literature) and Anselm A.Parlatore M.D (Resident in Psychiatry,Mental Health Center, Dartmouth MedicalSchool), co-editors. Hanover: GranitePublications, 1972. A Granite Chapbook No.1. With notes on contributors. $2.

Northern Lights is an appropriate title, with bright spots in this poetry anthology from the Hanover region. As might be expected, some of the more powerful beacons in this sky can be traced to their sources within the College, the "gown" half of the community. The English department is well constellated, with strong poems by Professors Eberhart, Heffernan, Lea, Siegel, and Vance. The Art, German, French, and Russian departments are also well-represented. But light of equal intensity is emitted by the "town"; over and over again, we are told in the contributors' notes that Rosellen Brown "is now living in Orford," that Frances Lindsay "is living in Hanover," that Michael McMahon "lives in New London." It is almost as if these places were the poets' occupations and the sources of their inspiration, a feeling which is strengthened when one reads the poems.

For this community of poets, living in New England is a hard, but worthwhile, occupation. Like Frost, a poet they can't help resembling, they know the dark side, the thin soil, the barriers among people. Margaret Thoms says that "the wonder of survival is caressing me." David H. Watters, the lone Dartmouth student in this anthology, writes an "Epithalamion" of sterility: the bride and groom live in adjoining valleys and never meet. The groom, a dairy farmer, sings this wedding song: "I believe in artificial insemination." Rosellen Brown and Michael McMahon write poems about the muskrat and the rat, two animals which New Englanders could regard as totems. In "Muskrat Hunting," "you" (the muskrat) are "trapped at the toothpick ankle." You chew through your leg and hobble off, to "start a new life on three legs." The rats in "At the Dump" "become students of failure/and know/waxed milk cartons do not burn/so much as collapse/inwardly/like men ashamed of their lives."

The poems are not merely morbid; they present, instead, honest slices of severe New England lives. In Dick Bernstein's poem about carp, "Hearts stalled, pretty/Neighbors yellowed and became widows." Along with the dump, the graveyard is a favorite place for images, for death is an ever-present fact in these poems. Robert Siegel even finds death catalogued in the library - "that staid/smell of old authors shrinking in the cellar."

But the common ground of these poems is not their involvement with death, but rather their ability to look at the worst without flinching. Even when Mel Goertz, undergoing a barium x-ray, says in "The Johnny" that she is "afraid to look at my inner life spilled out all over a screen," she has looked. All these poets have looked. None of them seems afraid.

Mr. Liman, Assistant Professor of English atLakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario,teaches American Literature and creativewriting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEducation in the Round

June 1974 By ANDREW J. NEWMAN AND MELANIE FISHER -

Feature

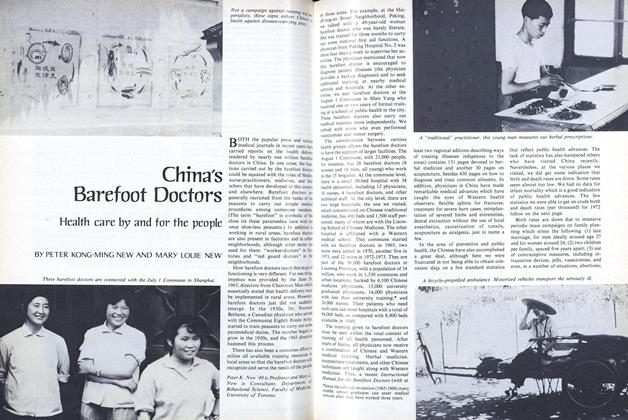

FeatureChina's Barefoot Doctors

June 1974 By PETER KONG-MING NEW AND MARY LOUIE NEW -

Feature

FeatureCASTLES ON THE CONNECTICUT

June 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureO Pioneers

June 1974 -

Feature

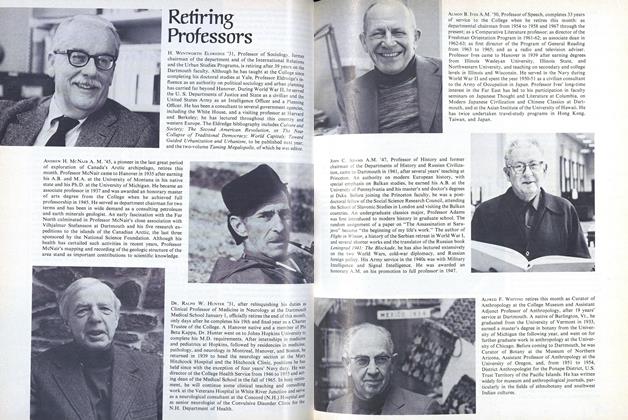

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Article

ArticleRetirement: Plan It and Enjoy

June 1974 By RICHARD S. BURKE '29

CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

October 1956 -

Books

Books"GOOD EYES FOR LIFE."

April 1934 By E. H. Carleton, M.D. -

Books

BooksVICTORIAN ORIGINS OF THE BRITISH WELFARE STATE

May 1961 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksHAPPY BIRTHDAY TO YOU!

November 1959 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksIN THE WORLD OF THE ROMANS

February 1946 By R. H. Lanphear '25 -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF PITNEY-BOWES.

October 1961 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR.