NO PEACE BEYOND THE LINE: THE ENGLISH IN THE CARIBBEAN 1624-1690.

OCTOBER 1972 JERE R. DANIELL IIBy Carl and Roberta Bridenbaugh'25. New York: Oxford University Press,1972. 440 pp. With 17 plates. $12.50.

Carl Bridenbaugh is one of America's most prolific and highly respected colonial historians. His books — the number of major works now has reached nearly a dozen — focus on the social dimensions of early American life and range in content from a study of colonial craftsmen to a general description of transatlantic religious faiths of the 18th century. This most recent volume is co-authored by his wife Roberta, and appears as the second part in what promises to be a lengthy series' on "the beginnings of the American people." The subtitle describes only part of what the Bridenbaughs discuss: No Peace Beyond the Line concentrates as much on Irishmen and Africans who lived in the British West Indies as upon "the English."

None of the three groups found life in the Caribbean especially pleasant. Forcibly dragged from their homeland, the Africans struggled to preserve some sense of dignity within the framework of slavery. According to the Bridenbaughs the lot of the Irish indentured servants was little better: greedy masters intent on maximizing profits treated them like slaves and often reneged on the indenture contracts. Englishmen had a rough time too, despite their favored position in the social and economic hierarchy. Wars with the French and Dutch, raids by native Caribs, the possibility of slave rebellion, disease, fire, hurricanes, and an occasional earthquake made disaster an everpresent phenomenon. Two out of three Europeans who settled in Jamaica following its conquest died within five years. Only a very few Englishmen in the islands as a whole lived long enough to become prosperous. The greatest strength of No Peace Beyondthe Line lies in the richness with which the Bridenbaughs describe settlement living conditions.

The greatest weakness is the unfortunate tendency of the Bridenbaughs to project their own values on the people they discuss. It is difficult for them not to judge African culture negatively, and to avoid articulating some of the racial stereotypes long present in Anglo-Saxon literature. The sentence "The most attractive positive trait of the blacks of both sexes, which stemmed in part from their great sexual desire, was their devotion to family life," (p. 234) reflects this difficulty, as does the comment that "A surprising number of Negroes, freshly arrived from Africa, had skills that enabled them to serve on plantations as carpenters, masons, bricklayers . . ." etc. (p. 302). The surprise is hardly necessary in the context of our present knowledge of West African culture. Similarly, the Bridenbaughs make clear their disapproval of the economically successful planters who by the end of the century dominated island life. The book's final chapter is labeled "Material Success and Social Failure" and has as its central theme the "shocking deficiency in the moral and religious condition of the inhabitants" (p. 393) which is blamed, in part, on the weakness of the Church of England.

These comments are meant to forwarn rather than discourage potential readers. NoPeace Beyond the Line still provides the most complete and accurate description of 17th-century English settlement in the Caribbean yet published.

A member of the Department of History atDartmouth, Professor Daniell teachescourses in Black America, Colonial America,and The Age of the American Revolution.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

October 1972 -

Feature

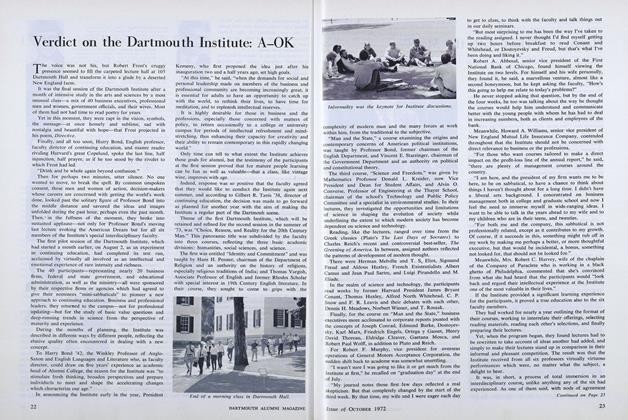

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

October 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

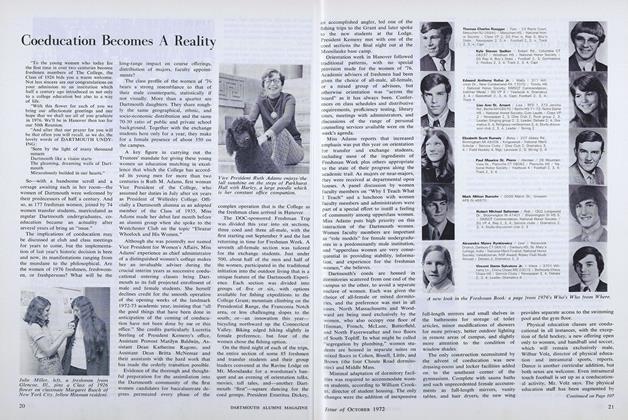

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

October 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

October 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

October 1972 -

Feature

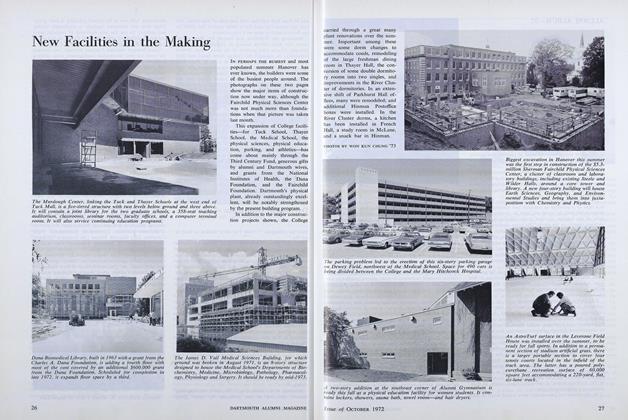

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

October 1972

Books

-

Books

BooksREADING THE SPIRIT

January 1937 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksTHESE WERE ACTORS.

January 1956 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksSAMSON OCCOM

June 1936 By James Dow McCallum -

Books

BooksTrade Associations

August 1921 By James P. Richardson -

Books

BooksANAMORPHOSIS OF EVE: A POEM CREATED IN SERIGRAPHY

November 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksImages

APRIL • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77