Race at Dartmouth

BACK in 1958 I recall listening to an African student on a soap box in Hyde Park in London haranguing the crowd, and one of the things he said was that he had come to England to get an education in order to go home and throw the British out. His was a comparatively simple revolutionary task. One of the things which has bedeviled the black minority in this country is that its task cannot be stated or conceptualized so neatly.

Blacks do not come to Dartmouth so that they can go home to throw the white man out. Oh, there is some of that, necessarily. The education of the black community has as a goal the gaining of a greater degree of control over its destiny, control now being exercised by whites. Knowledge is power. That fear of expulsion from some of the seats of power probably underlies the DeFunis issue, the so-called issue of reverse discrimination.

The other dominant reality is that white America is not going anywhere, it is not leaving. The task is not one of expulsion but of change, of conversion which implies a mixture of pushing and shoving, battle, cajoling, appeal, conviction of guilt, communication, and whatever else it takes. For America to change, there must be some sort of collaboration, some sort of contact, whether it be the kind of camaraderie which characterized the relations of blacks and liberals during the civil rights movement or the sharp injunction of Black Power which advised white liberal types to change their community while blacks worked at getting themselves together.

All of the verbiage about self-segregation and reverse racism and reverse discrimination and separatism and integration merely clouds the issue if it does not recognize that the dilemma has two horns. The situation of black America is dialectical. At least two things are going on at once. W. E. B. DuBois years ago observed the dilemma, not only as an external but an internal reality. His is the classic formulation of the problem.

One feels his two-ness [DuBois wrote] an American Negro, two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife; this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better, truer self. He would not Africanize America for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach the Negro's soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon.

But the problem is not a black problem only, it is a white problem as well. A white friend of mine - some of my best friends are white - observed once with Pogo, "We have met the enemy and they are us." White America designed the problem and maintains the structures that continue to make it a problem. Racism is a white not a black invention. The task of blacks is to figure out ways to combat it and so increase our freedom. The task of whites is to find the source of the problem in themselves and this society and root it out. Unfortunately for both, whites encounter it as a problem only when they encounter blacks. But blacks, because they live in a predominantly white society, encounter the problem - or suspect they do everywhere. For blacks it is a short-term and a long-term issue. For whites it is a long-term issue, but only when blacks push is it an immediate question. It is a long-term issue because America cannot be at peace with the contemporary version of a society half slave and half free any more than she could with the original version a century ago.

The College appears to have had two interlocking intentions five years ago when it increased its black enrollment. They were to make a Dartmouth education available to more blacks and to enhance the Dartmouth experience. One cannot be done without the other. Neither can be done without the cooperation of the students and the faculty and the administration, white and black. If the goals are legitimate, then the demands required to attain them must be legitimate also.

In order to make a Dartmouth education available to blacks, that education must change. This has been only partly perceived. Some remedial structures have been established for students who have not had the benefit of quality secondary schools to prepare them for this experience. But little conscious follow-through seems to exist beyond that point. Students are given an initial push and left on their own, which is fine for many but disastrous for a few. Some further attention to this issue might be of help to non-blacks as well. The necessity for representation by blacks in faculty and administrative posts has been recognized, though implementation in some areas is uncomfortably far beyond that in others. It is evident that the commitment on this level is by no means uniform. That is not surprising but neither is it particularly helpful.

One thing many students complain about is that apart from the Black Studies Program, the College faculty as a whole does not appear to have seen any connection between the changed student involvement and their appreciation or treatment of academic material. The paucity of treatment of the accomplishments of blacks except by blacks, the tacit assumptions of European value and non-European disvalue, crop up enough for some to be concerned about it. Faculty members might usefully reflect upon this perception individually and as a group. Doubtless blacks suffer from a kind of paranoia. Having a personal as well as a group history of persecution and denigration, we are likely to see racism even where no racism is. Contrarily, whites, having no first-hand knowledge of such a ubiquitous experience, are likely to discount all but the most blatant forms of it. Obviously, you will cry first if your ox is gored, but if someone cries it is wise to look to the ox. Protection of "academic freedom" will do as well as opposition to "forced busing" to mask racism. The academic enterprise does not have the responsibility to falsify the record by declaring that minority people did what they did not, or did better than they did. It does have a responsibility to be even-handed, which means to address the imbalance resulting from the long neglect of things black or non-European. Racism is in part the tendency to judge everything from the perspective of what is important to Americans of European descent. In a country in which other groups exist and are educated, the tacit if not overt message is clear.

When I was in high school, "world history" consisted of tracing the development of American life from the fertile crescent to Egypt, to Greece, to Rome, to northern Europe, to America. Asia existed only as a setting for Marco Polo and to invent gunpowder. Africa existed only to supply slaves and, later, colonies. Apart from Mexico, Latin America did not exist at all. That was not world history. It was the history of the development of modern American technology and that from a very limited perspective. Sensitivity to such issues is necessary if a Dartmouth education is not just an indoctrination into middle- or upper-class American values. And sensitivity to such issues benefits not only blacks but the College at large, just as the expansion of my world history course to include the real world would have benefited everyone who took it.

The other intent of increasing the black enrollment was to enrich the Dartmouth experience. This policy assumes that there is something the College can learn by making a commitment in this area. Some of what it learns will come in ways already outlined, but there are other things to be learned only through self-conscious interaction. Part of the Dartmouth experience is grappling with the minds you will encounter in the world. In a largely segregated society we not only have to grapple with issues racially defined, but because we live together we have to learn the minds of those across the divide. As the psalmist says, we have "to leap over the wall." We shall not solve America's least tractable problem here, but we may develop a grasp of it and its possibilities for solution which may serve us hereafter. A responsibility falls on both black and white, a responsibility to interact and to communicate if each is to capitalize upon the context in which we are set. Our society is not so well along that the opportunity for peers to communicate across racial lines in a meaningful way is a regular occurrence. For whites, black sensitivity and preoccupation must be a mystery; for blacks, white ignorance of the issues that shaped black daily life is an annoyance. If the enterprise of increasing knowledge and understanding means anything, it is relevant here.

I have said that the task of blacks in America is dialectical, it is two-pronged, it involves two tasks that interrelate: the sustenance of the black community and the apprehension and conversion of the white community. If blacks did not think there were some values to be gained by being at Dartmouth, they would not have come. If the College did not think it would gain by our being here, we would not be. Blacks did not come to the white academy to be separate, and the College did not admit blacks to isolate them. Yet blacks, many blacks, feel a need to associate with blacks and to have their own thing, and that is a legitimate concern because we ought by now to have learned the truth, for our situation, of Ben Franklin's admonition to the colonies, "Either we hang together or we hang separately." America judges people by the groups with which they are identified, and until a group gets its thing together, is recognized and establishes itself as a community of interest to be dealt with, the individual is not likely to get very far. So the Afro-American center, for instance, makes sense, the Black Studies program makes sense, and they are likely to make sense for some time to come. Only when the general society makes some basic changes will the need for such structures fade away and then only because those they serve decide other means of expression and support are preferable.

On the other hand here we are in the white academy with the opportunity and responsibility to interact so that we, black and white, significantly change the Dartmouth experience. This is awkward for blacks because it usually means taking the first step. We always complain that the burden of changing society rests on us. The black has to work harder to get to the same place - harder intellectually, or at showing initiative or drive, or developing the simple ability to take what's handed out and keep on.

To maintain some sense of black community on one hand, and to participate fully in the Dartmouth community on the other is a double task, but that I think should be our goal. Ours remains for the present a dual identity and we neglect either at our peril. To be absorbed in the black community is to be shut out from many of the benefits of the College and, to a degree, from the possibility of changing it; total absorption in those benefits, however, may well mean being strung out at some later point, divorced from one's base and identity.

I can recall fighting for the elimination of exclusive clauses in fraternities my freshman year at Dartmouth way back in the '50s, and I can remember joining one and making my brothers periodically aware of the meaning of American society from where I stood and how it differed from their perception, something I think was profitable to both. Whites do not escape this responsibility for interacting. It is not enough merely to be there and to be open. It is interesting that students will go as Tucker Foundation interns to Jersey City to make encounters that are apparently too threatening here at home. I am not suggesting they should not go, but that they should see the relevance of that experience here as well. The fear of going to an Afro-American center event may derive from a fear of reversing the minority experience briefly - something that would be salutary for most. Most blacks have had to deal with inhospitality and while that is no excuse for it on their part, neither should it be an effective deterrent for whites.

It seems tacitly assumed by many that courses in minority affairs are the preserves of minorities, but clearly that is not so and should not be. Minority people have been miseducated in America but so have whites. One needs the exposure to better understand their personal experience, the other needs it to understand the American experience. Understanding one's neighbors frequently has implications for understanding oneself, so that interaction is an academic as well as a personal and extracurricular matter. The kind of interaction I am speaking of will not happen naturally. It hasn't. Where it has occurred it did so because someone, black or white, felt it was important and took the initiative. Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, who taught philosophy here at Dartmouth, used to say, "Things left to themselves do not get better, they deterioriate."

Such interaction has its price. It will require both sides to give something. Each will become vulnerable to the other, run the risk of being made a fool of to serve the other's pain or vanity. But such interactions could significantly alter life on this campus and the things each group learns. Generally, it may be said that blacks living in a predominantly white society know whites better than whites know blacks, but that is less true now than 50 years ago. It is worthwhile to know how the other perceives you and how he or she sees you as an individual. Undergraduates at the College are not locked into the goose step of racism that has haunted the West; neither black nor white is irredeemable at this stage. Theirs is the inheritance but not the record. They can encounter one another as human beings and see what comes of it. They will not like everything they see, but at worst the students will also know better what they do not like and why.

One of the goals of such interaction should be honest exchange, so that no one is required to pull punches. What each is required to do is really listen and, at least for the duration of the listening, to care. The problem here or elsewhere cannot be solved until people want to solve it enough to take some risks. The problem is probably not unbearable. In a recent Sunday evening Chapel service I said to the students:

You will not be moved to take the risk because you are driven to it, because you must. I propose it because you are free to refuse it and by the same token free to take it up because you envision something better than the kind of stand-off which now largely exists. That is the motive, the vision at least in one place, this place, of another kind of option. The option we all say we want, the only real option for the nation, the encounter of men and women as such, as persons, not exhausted by our group or race. All changes in society cost something. Leadership belongs only to those who understand that and are willing to pay the price. It would be nice to think this college might train some - leaders that is. The possibilities are as various as the people involved. The College has just begun to realize its intention. Whether it does and how well it does is finally up to you and what you wish to spend of yourselves on your education and your life

The prophet Jeremiah wrote to the Hebrews who were carried from Jerusalem into exile in Babylon, "Build houses and live in them: plant gardens and eat their produce . . . take wives and have sons and daughters. . . . But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you ... and pray to the Lord on its behalf for in its welfare you will find your welfare."

Maintain your integrity but seek the welfare of the city, of the place, of the academy "where I have sent you," make it as much for blacks or Asians or Native Americans as it is for anyone, fight when it is necessary to fight, collaborate when it is profitable to collaborate, but always be consciously part of the whole community and from your diverse perspectives seek its welfare-In the free and open interchange of peoples and ideas is the welfare of this "city" and our common enterprise best served.

This article is adapted from a Chapel talkby Warner Traynham '57, Dean of theTucker Foundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBeating the Odds

May 1975 By IRVING H. LEVITAS, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

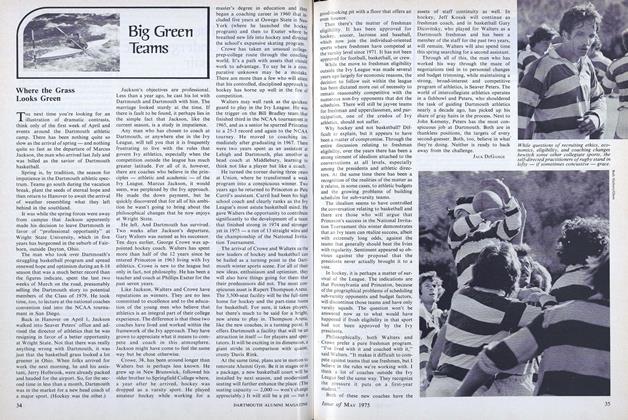

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON -

Article

ArticleThe Long Walk

May 1975 By OLIVE TARDIFF

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honesty That Is Dartmouth

JULY 1963 By ALAN KENNETH PALMER '63 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAre Americans Saving Enough?

JANUARY 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureRock chronicler

May 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureEmerson at Dartmouth

JANUARY 1968 By Michael L. Lasser '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77