THE next time you're looking for an illustration of dramatic contrasts, think only of the first week of April and events around the Dartmouth athletic camp. There has been nothing quite so slow as the arrival of spring - and nothing quite so fast as the departure of Marcus Jackson, the man who arrived last July and was billed as the savior of Dartmouth basketball.

Spring is, by tradition, the season for impatience in the Dartmouth athletic spectrum. Teams go south during the vacation break, plant the seeds of eternal hope and then return to Hanover to await the arrival of weather resembling what they left behind in the southland.

It was while the spring forces were away from campus that Jackson apparently made his decision to leave Dartmouth in favor of "professional opportunity" at Wright State University, which in five years has burgeoned in the suburb of Fair-born, outside Dayton, Ohio.

The man who took over Dartmouth's struggling basketball program and spread renewed hope and optimism during an 8-18 season that was a much better record than the figures indicate, spent the last two weeks of March on the road, presumably selling the Dartmouth story to potential members of the Class of 1979. He took time, too, to lecture at the national coaches convention tied into the NCAA tournament in San Diego.

Back in Hanover on April 1, Jackson walked into Seaver Peters' office and advised the director of athletics that he was resigning in favor of a better opportunity at Wright State. Not that there was really anything wrong with Dartmouth, it was just that the basketball grass looked a lot greener in Ohio. When folks arrived for work the next morning, he and his assistant, Jerry Holbrook, were already packed and headed for the airport. So, for the second time in less than a month, Dartmouth was in the market for a new head coach of a major sport. (Hockey was the other.)

Jackson's objectives are professional. Less than a year ago, he cast his lot with Dartmouth and Dartmouth with him. The marriage looked sturdy at the time. If there is fault to be found, it perhaps lies in the simple fact that Jackson, like the current season, is a study in impatience.

Any man who has chosen to coach at Dartmouth, or anywhere else in the Ivy League, will tell you that it is frequently frustrating to live with the rules that govern Ivy athletics, especially when the competition outside the league has much greater latitude. For all of it, however, there are coaches who believe in the principles - athletic and academic - of the Ivy League. Marcus Jackson, it would seem, was perplexed by the Ivy approach. He made the down payment, but he quickly discovered that for all of his ambition he wasn't going to bring about the philosophical changes that he now enjoys at Wright State.

He left. And Dartmouth has survived. Two weeks after Jackson's departure, Gary Walters was named as his successor. Ten days earlier, George Crowe was appointed hockey coach. Walters has spent more than half of the 12 years since he entered Princeton in 1963 living with Ivy athletics. Crowe is new to the league but only in fact, not philosophy. He has been a teacher and coach at Phillips Exeter for the past seven years.

Like Jackson, Walters and Crowe have reputations as winners. They are no less committed to excellence and to the education of the young men who believe that athletics is an integral part of their college experience. The difference is that these two coaches have lived and worked within the framework of the Ivy approach. They have grown to appreciate what it means to compete and coach in this atmosphere. Jackson might have come to feel the same way but he chose otherwise.

Crowe, 38, has been around longer than Walters but is perhaps less known. He grew up in New Brunswick, followed his older brother to Springfield College where, a year after he arrived, hockey was dropped as a varsity sport. He played amateur hockey while working for a master's degree in education and then began a coaching career in 1960 that ineluded five years at Oswego State in New York (where he launched the hockey program) and then to Exeter where he breathed new life into hockey and directed the school's expansive skating program.

Crowe has taken an unusual college-prep-college route through the coaching world. It's a path with assets that should work to advantage. To say he is a comparative unknown may be a mistake. There are more than a few who will attest that his controlled, disciplined approach to hockey has borne up well in the fire of competition.

Walters may well rank as the quickest guard to play in the Ivy League. He was the trigger on the Bill Bradley team that finished third in the NCAA tournament in 1965, and as a senior he spurred Princeton to a 25-3 record and again to the NCAA tourney. He moved to coaching immediately after graduating in 1967. There were two years spent as an assistant at Lehigh and Dartmouth, plus another as head coach at Middlebury, learning to think not like a player but like a coach.

He turned the corner during three years at Union, where he transformed a weak program into a conspicuous winner. Two years ago he returned to Princeton as Pete Carol's assistant. Carril had been his high school coach and clearly ranks as the Ivy League's most astute basketball mind. He gave Walters the opportunity to contribute significantly to the development of a team that finished strong in 1974 and stronger yet in 1975 - a run of 13 straight wins and the championship of the National Invitation Tournament.

The arrival of Crowe and Walters as the new leaders of hockey and basketball can be hailed as a turning point in the Dartmouth winter sports scene. For all of their new ideas, enthusiasm and optimism, they will also have things going for them that their predecessors did not. The most conspicuous asset is Rupert Thompson Arena. The 3,500-seat facility will be the full-time home for hockey and the part-time home for basketball. For sure, it takes players, but there's much to be said for a bright, new arena to play in. Thompson Arena, like the new coaches, is a turning point. It offers Dartmouth a facility that will be an attraction in itself - for players and spectators. It will be exciting in its dimension, a giant stride in comparison with quaint, crusty Davis Rink.

At the same time, plans are in motion to renovate Alumni Gym. Be it in stages or in a package, a new basketball court will be installed by next season, and modernized seating will further enhance the place. (The seating capacity - 2,000 - won't change appreciably.) It will still be a pit - but a good-looking pit with a floor that offers an even bounce.

Then there's the matter of freshman eligibility. It has been approved for hockey, soccer, lacrosse and baseball, which now join the individual-oriented sports where freshmen have competed at the varsity level since 1971. It has not been approved for football, basketball, or crew.

While the move to freshman eligibility outside the Ivy League was made several years ago largely for economic reasons, the decision to follow suit within the league has been dictated more out of necessity to remain reasonably competitive with the numerous non-Ivy opponents that dot the schedules. There will still be jayvee teams for freshman and upperclassmen, and participation, one of the credos of Ivy athletics, should not suffer.

Why hockey and not basketball? Difficult to explain, but it appears to have been a matter of compromise. Through the entire discussion relating to freshman eligibility, over the years there has been a strong element of idealism attached to the conversations at all levels, especially among the presidents and athletic directors. At the same time there has been a recognition of the realities of the matter as it relates, in some cases, to athletic budgets and the growing problems of building schedules for. sub-varsity teams.

The idealism seems to have controlled the conversation relating to basketball and there are those who will argue that Princeton's success in the National Invitation Tournament this winter demonstrates that an Ivy team can realize success, albeit with extremely long odds, against the teams that generally should beat the Ivies with regularity. Sentiment appeared so obvious against the proposal that the presidents never actually brought it to a vote.

In hockey, it is perhaps a matter of survival of the League. The indications are that Pennsylvania and Princeton, because of the geographical problems of scheduling sub-varsity opponents and budget factors, will discontinue those teams and have only varsity squads. The question won't be answered now as to what would have happened if frosh eligibility in that sport had not been approved by the Ivy presidents.

Philosophically, both Walters and Crowe prefer a pure freshman program. "I've lived with it and coached with it," said Walters. "It makes it difficult to compete against teams that use freshmen, but I believe in the rules we're working with. I think a lot of coaches outside the Ivy League feel the same way. They recognize the pressure it puts on a first-year student."

Both of these new coaches have the assets of staff continuity as well. In hockey, Jeff Kosak will continue as freshman coach, and in basketball Gary Dicovitsky, who played for Walters as a Dartmouth freshman and has been a member of the staff for the past two years, will remain. Walters will also spend time this spring searching for a second assistant.

Through all of this, the man who has worked his way through the maze of negotiations tied in to personnel changes and budget trimming, while maintaining a strong, broad-interest and competitive program of athletics, is Seaver Peters. The world of intercollegiate athletics operates in a fishbowl and Peters, who shouldered the task of guiding Dartmouth athletics nearly a decade ago, has picked up his share of gray hairs in the process. Next to John Kemeny, Peters has the most conspicuous job at Dartmouth. Both are in thankless positions, the targets of every second-guesser. Both, too, believe in what' they're doing. Neither is ready to back away from the challenge.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBeating the Odds

May 1975 By IRVING H. LEVITAS, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON -

Article

ArticleThe Long Walk

May 1975 By OLIVE TARDIFF

JACK DEGANGE

-

Article

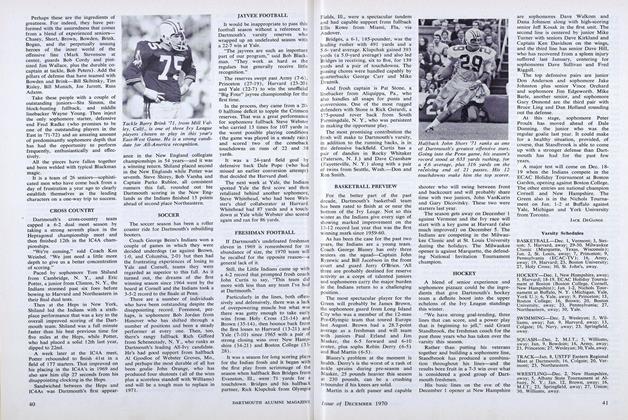

ArticleFRESHMAN FOOTBALL

DECEMBER 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleOTHER WINTER SPORTS

JANUARY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleGOLF

MAY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

FEBRUARY 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN FOOTBALL

DECEMBER 1972 By Jack DeGange -

Article

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH NIGHT CELEBRATED DESPITE HEAVY RAIN

November, 1025 -

Article

ArticleEPSILON KAPPA PHI RETAINS HIGH SCHOLARSHIP EMBLEM

December, 1925 -

Article

ArticleMagazine Editor on Leave

November 1928 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Night

June 1949 -

Article

ArticleGive A Rouse

Sept/Oct 2007 -

Article

ArticleCOOPERATIVE EATING CLUB

February 1936 By W.J. Minsch Jr. '36