From: André Maurois To: The Students Subject: Food

Dartmouth is at the edge of a forest. In theevening the students carry their dinner andtheir books into the depths of the woods.During fine weather they pass the nightthere and the farther away the better forthem.

ANDRÉ MAUROIS, 1928

Ah, mes enfants, you may well ask who is this alien who comments thus on Dartmouth eating habits? And, tiens, on what experience does he base his knowledge?

Eh bien, my fellow journalist, the learned Westbrook Pegler, once wrote, "The French avoid no hazards, they take food as it comes without false restrictions on style or stance and they make their victuals holler 'uncle!'" On this credential I base my following observations.

You, you étudiants of 1975, may no longer carry your dinner and your books into the depths of the woods. You may trudge through the four serving lines of Thayer Hall to see what la viandemysterieuse is being served that day. Freshman Commons is gone from College Hall. Ma Smalley's, the Rood Club and the Plaid Pig are no longer, the eating clubs of yore.

But you are en rapport with Dartmouth students from the days of the romantic John Ledyard to the veriest weenie of today in one thing: you complain about the food. Mori Dieux, how you complain!

A Dr. Belknap of Dover, New Hampshire, wrote in 1774 of the new college in the depths of the woods: "The scholars say they scarce ever have anything but pork and greens without vinegar, and pork and potatoes, that fresh meat comes but very seldom, and that the victuals are very badly dressed."

Le Cure M. Wheelock tried to answer the charge, admitting, vraiment, that "they have not had a fullness of milk." Further, he confessed, "sometimes the cooks have made mistakes ... last week there was a gross mistake made, the pudden was not well salted." He pointed out, however, with some colère, that "most of the scholars are well content and they live better than some respectable farmers in the country generally do."

The Trustees of the College of that day, solicitous of the students as are the Trustees of this day, made the following report at Commencement time, 1774: "That for a few days some Beef was served by the cooks which (tho' accidentally tainted in a small degree) was judged by them to be such as the Students would generally approve [the genesis, perhaps, of la viande mysterieuse?], which tho' it appears offensive to some, yet there were served at the same time a plenty of good wholesome provisions. ..."

This culinary leger-de-main, hiding the accidentally tainted meat under a cloak of "plenty of good wholesome provisions" is a trick as old as academe. Perhaps plus ancien, for was it not Lucretius who said, "What is food to one may be fierce poison to others"?

An attempt was made in the early 19th century to install a commons system for the feeding of the students. In 1805 a committee of the faculty - ah, oui, they had faculty committees even that long ago! - recommended the hiring of a steward "to oversee, inspect, and prudently manage every particular respecting commons to the best advantage for the students."

This arrangement did not last long, for it is recorded that as soon as 1815 the students rebelled. "At one time," the historian M. Chase reports, "the butter being persistently strong, one of the students - afterward a distinguished lawyer of this State - was deputed, while all the others stood at their places, to apostrophize the offensive stuff and bid it 'down' from their sight." M. Chase added that the students' complaints "resulted in the final discontinuance of the whole system. The Trustees have never since thought it wise to resume it."

M. Chase, naturalment, could not see the future. He could not know that nearly 100 years later the Trustees would cause to be erected, at a munificent sum of $120,000, College Hall. This would house not only, as the historian M. Lord tells us, "a living room for the College Club, of which all students were members, a reading room, and a trophy room," but also "a large dining hall beautifully finished in Flemish oak and capable of seating nearly four hundred at table."

Far from, quand même, having to "provide their own plates, knives, forks, teacups and tea," as the historian M. Hill recounts of the early Wheelock years of the College, "a five-piece student orchestra played at dinner in the College Hall Commons" in the 1930s and in the new Thayer Hall (1937) "a dining room was set aside for seniors who wished to be waited on."

Flemish oak makes no escargots or sautes no Chateaubriand, but it is, how shall we say, a different ambience from green coats and plastique trays. As for five-piece orchestra, they, too, have gone the way of the servitors for seniors, but at the same time those innocents of the 1930s did not have I.D. credit cards, either.

"I hope," wrote Le Cure M. Wheelock, in 1773, "Providence designs to deliver us from the plague of unskillful, deceitful, and unfaithful cooks."

Enfin, this is not the case in this siecle! But, attention:

La plus ca change, la plus c'est la mèmechose.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

October 1975 By WILLIAM J. MONTGOMERY, STEPHEN R. PARKHURST

JAMES L. FARLEY '42

-

Article

ArticleWar Story of Jiggs Donahue '15

November 1946 By James L. Farley '42 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

MARCH 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Books

BooksPhiloprogenitive Man

December 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Books

BooksBig Muscle, Big Bucks

December 1980 By James L. Farley '42

Features

-

Feature

FeatureB.E./M.B.A. Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

JUNE 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55 -

Feature

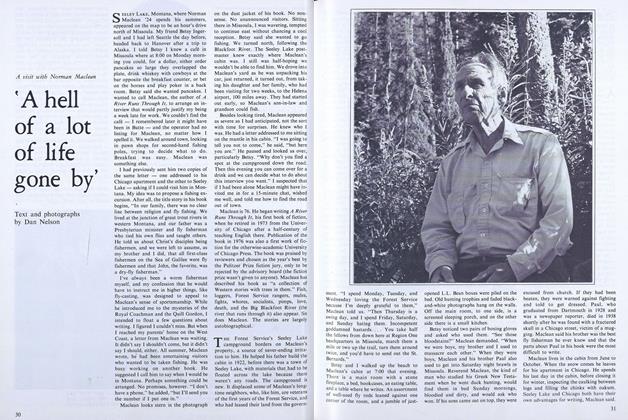

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

FeatureRecommended Reading

Sept/Oct 2010 By LAUREN BOWMAN ’11 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1957 By William G. Morton '28