HANOVER, as we all know, has never had a railroad. In light of the geographical problems of ascending to Hanover Plain, and the proximity of the Norwich and Hanover station in Lewiston, the lack of a railroad isn't particularly surprising.

What has always seemed to me remarkable is that nobody ever built a rural trolley line between White River Junction and Hanover, possibly with a branch to Lebanon. Such lines were common in rural New England, and several - Waterbury to Stowe, Vermont, for example - were no more promising than a connection from Dartmouth to the principal local railroad station. Hanover in 1900 was a town of 1,884 people, and the College had 741 students; then as now the College and the town attracted visitors continually throughout the year, and the faculty were habitual travelers. Two daily trains from White River Junction to Boston, plus one on Sundays, had no connections from the Connecticut River line, on which the Norwich and Hanover station was located. Worse, most southbound trains on the Central Vermont had no northbound connections on the Connecticut River line. The road was five miles of dirt - a relatively long buggy ride.

In addition, the College completed its present heating plant in May 1899, and was burning about 1,200 tons of coal per year, all laboriously dragged up from Lewiston in horsedrawn vehicles at a drayage cost of about 40 cents per ton.

A rural trolley line could have dealt with both these problems and, inevitably, the attractions of an electric railway were not lost on Dartmouth or on local entrepreneurs. The first proposal for such a line came from the College in 1898, when an engineering class at Thayer surveyed a route and planned the hardware in great detail. The line was to originate at the Union Depot in White River Junction, and pass through Hartford over the bridge to West Lebanon, where the Thayer students projected an interchange for the College's coal with the Boston & Maine.

The electric line would have proceeded north beside the West Lebanon-Hanover road, but the route would have had to deviate from the road to avoid grades north of Wilder. By sticking to the escarpment of the hills or crossing meadow land, much of which was owned by the College, a relatively flat route to the east could have been achieved. The Thayer students proposed ascending Hanover Plain to the east of the ravine behind the present Hanover High School and entering the town on Lebanon Street, presumably to a terminus at Main Street. A spur would have been run to the heating plant, and a small yard of perhaps two tracks would have been provided for inbound coal and lumber movements into Hanover. The yard could also have served for passenger equipment laying over during football games.

The Thayer students estimated that the fixed physical plant could have been built for $10,000 per mile, or $50,000. Two closed and two or three open cars would probably have been adequate for the Hanover line's traffic. An electric locomotive or a combine capable of hauling a hopper car of coal would have been required, along with a work motor for maintenance of track and overhead and a snow sweeper. Cars would have cost about $4,000 each.

The students proposed that the line be powered by electricity from the hydropower installation of the Mascoma Electric Light Company at Centerville, on the White River three and a half miles north of the Junction. The entire trolley line, including fixed plant, rolling stock, and electrical connections, would have required investment of $75,000 to $100,000. Alas, as the Hanover Gazette correctly reported, "There is no prospect that the road will be built, now or at any time in the future."

However, two electric railways were chartered in Vermont to serve Hanover, one of which was widely expected to be built. This was the Hartford Street Railway, chartered in 1894 to build a streetcar line from White River Junction to Hartford Village and Olcott, which was to become Wilder in 1898. As the boom in building electric railways spread in the early years of the 20th century, the backers, who were mainly merchants of White River Junction, expanded their plans to serve Hanover by running north through Wilder to Norwich and crossing the Connecticut at Lewiston. This was intended to be a pure streetcar operation, and there is no evidence of any intention to carry freight. The ascent of West Wheelock Street from the Ledyard Bridge would have been impossible for cars of coal in any case. This line was intended to provide service, probably from the west side of Main and West Wheelock, to the station at White River Junction in 15 minutes for a nickel fare. It was never financed and its charter was declared void in 1918.

A more grandiose and far less practical Proposal for a system of electric lines from White River Junction was chartered in 1902 as the Inter-State Railway Company. The promoters, who were mainly financiers connected with the First National Bank and the Inter-State Trust Company, proposed lines running radially from White River Junction to Bethel on the west, Wells River on the north, Bellows Falls on the south, and Lebanon on the east. Hanover would have been served by a branch off the Lebanon line from West Lebanon which would have continued to a junction with the Wells River line at Norwich. The route would probably have been a combination of the Thayer students' projected entry via Lebanon Street and the Hartford Street Railway's entry on West Wheelock, with a block of single track down Main Street between the two.

The Inter-State Railway was based on the expectation that White River Junction's strategic location at a major railroad crossing would cause it to become a major metropolis. This, of course, did not happen, and the Inter-State was never built. The price level rose steadily from 1896, so that the cost estimates of the Thayer students were obsolete by even the early years of the 20th century. In addition, electric railways of all sorts quickly proved themselves less profitable than had been anticipated. The boom years ended abruptly with the Panic of 1907, and so did the prospect of building lines in an area as lightly populated as White River Junction-Lebanon-Hanover.

If any of the lines had been built, how long could it have survived? The hard-surfaced highways which spread about the country in the early 1920s wiped out most of the New England rural trolley lines, and whatever served Hanover would probably have been no exception. The line projected by the Thayer students would have had the greatest survival potential of the three, owing to its traffic in coal for the College.

The projected route had the further advantage of running directly past Memorial Field, so that it would have been well suited to handling football crowds. The crowds of the immediate post-war era would have required every available car, open and closed alike, so that we might have shared with our brethren at Yale the experience of hordes of football fans, in raccoon coats and with hip flasks, arriving on open cars even in blizzards for games each fall. The conversion of the College's heating plant from coal to oil in 1922 would undoubtedly have hastened the end.

Thereafter, Hanover would be as it is today, except for some lightly-graded embankment in the meadows southeast of town, two prominent bridge abutments at Mink Brook, some worthless bonds in local attics, and some charming memories among the older alumni.

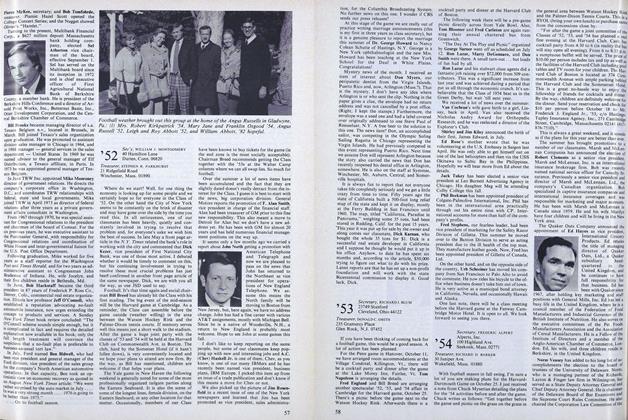

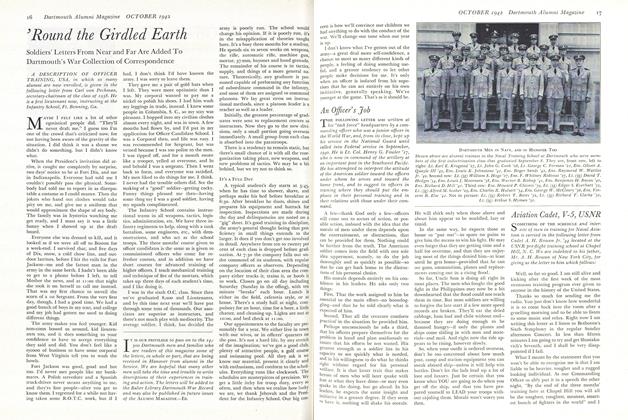

The way we weren't: all the men wear hats on the trolley in Berlin, New Hampshire.

On the economics faculty at UCLA,George Hilton '46 spent last year as aVisiting Professor at Tuck School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

October 1975 By WILLIAM J. MONTGOMERY, STEPHEN R. PARKHURST

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRACK

May 1912 -

Article

ArticleFURTHER APPRAISALS OF THE WORK OF DR. TUCKER

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

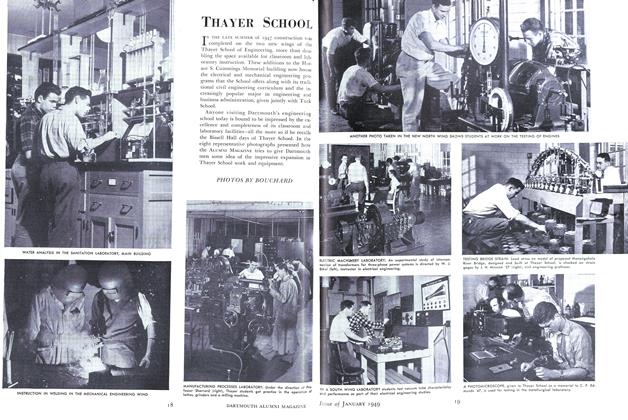

ArticleThayer School

January 1949 -

Article

ArticleWe Asked 100 Students: Who Would Make a Good Montgomery Fellow?

MAY 1996 -

Article

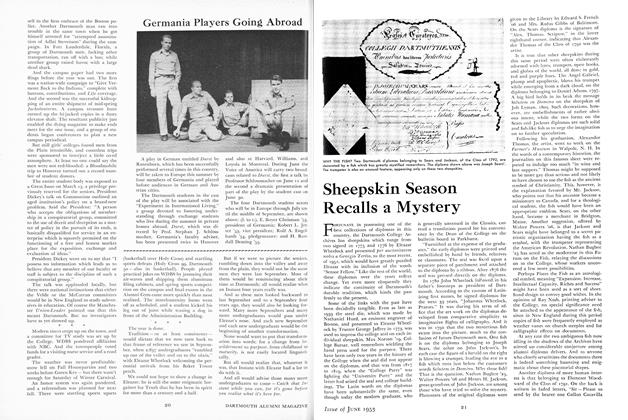

ArticleSheepskin Season Recalls a Mystery

June 1953 By Alice Pollard -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

October 1942 By John French JR. '30