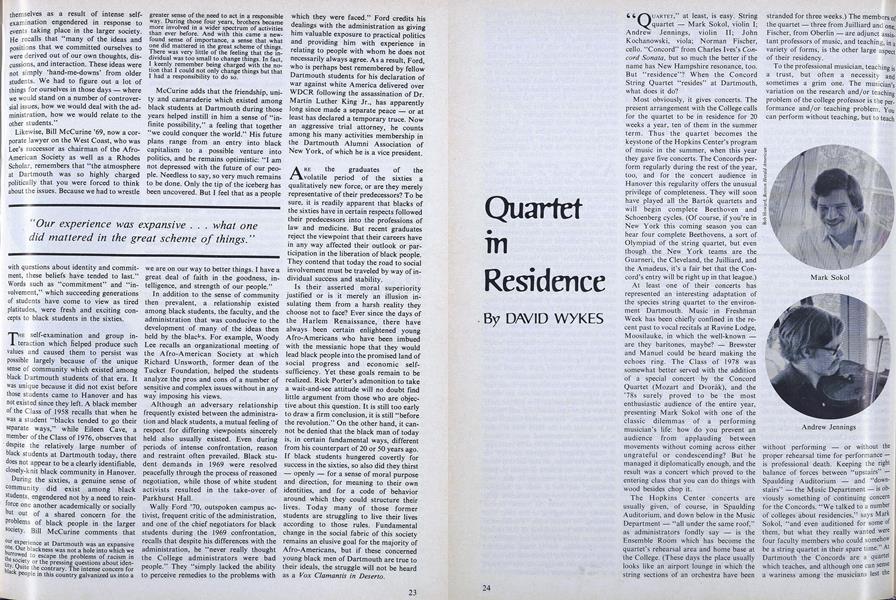

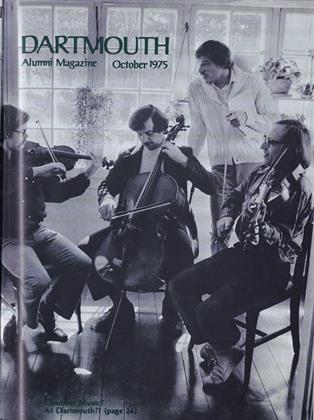

"QUARTET," at least, is easy. String Wquartet - Mark Sokol, violin I; Andrew Jennings, violin II; John Kochanowski, viola; Norman Fischer, cello. "Concord" from Charles Ives's Concord Sonata, but so much the better if the name has New Hampshire resonance, too. But "residence"? When the Concord String Quartet "resides" at Dartmouth, what does it do?

Most obviously, it gives concerts. The present arrangement with the College calls for the quartet to be in residence for 20 weeks a year, ten of them in the summer term. Thus the quartet becomes the keystone of the Hopkins Center's program of music in the summer, when this year they gave five concerts. The Concords perform regularly during the rest of the year, too, and for the concert audience in Hanover this regularity offers the unusual privilege of completeness. They will soon have played all the Bartok quartets and will begin complete Beethoven and Schoenberg cycles. (Of course, if you're in New York this coming season you can hear four complete Beethovens, a sort of Olympiad of the string quartet, but even though the New York teams are the Guarneri, the Cleveland, the Juilliard, and the Amadeus, it's a fair bet that the Concord's entry will be right up in that league.)

At least one of their concerts has represented an interesting adaptation of the species string quartet to the environment Dartmouth. Music in Freshman Week has been chiefly confined in the recent past to vocal recitals at Ravine Lodge, Moosilauke, in which the well-known - are they baritones, maybe? - Brewster and Manuel could be heard making the echoes ring. The Class of 1978 was somewhat better served with the addition of a special concert by the Concord Quartet (Mozart and Dvorak), and the '78s surely proved to be the most enthusiastic audience of the entire year, presenting Mark Sokol with one of the classic dilemmas of a performing musician's life: how do you prevent an audience from applauding between movements without coming across either ungrateful or condescending? But he managed it diplomatically enough, and the result was a concert which proved to the entering class that you can do things with wood besides chop it.

The Hopkins Center concerts are usually given, of course, in Spaulding Auditorium, and down below in the Music Department - "all under the same roof," as administrators fondly say - is the Ensemble Room which has become the quartet's rehearsal area and home base at the College. (These days the place usually looks like an airport lounge in which the string sections of an orchestra have been stranded for three weeks.) The members of the quartet - three from Juilliard and one Fischer, from Oberlin - are adjunct assistant professors of music, and teaching, in a variety of forms, is the other large aspect of their residency.

To the professional musician, teaching is a trust, but often a necessity and sometimes a grim one. The musician's variation on the research and/or teaching problem of the college professor is the performance and/or teaching problem. You can perform without teaching, but to teach without performing - or without the proper rehearsal time for performance - is professional death. Keeping the right balance of forces between "upstairs" - Spaulding Auditorium - and "downstairs" - the Music Department - is obviously something of continuing concern for the Concords. "We talked to a number of colleges about residencies," says Mark Sokol, "and even auditioned for some of them, but what they really wanted were four faculty members who could somehow be a string quartet in their spare time." At Dartmouth the Concords are a quartet which teaches, and although one can sense a wariness among the musicians lest the teaching begin to encroach too far on the rehearsal time, at present the balance seems to be about right, a fact which probably owes a lot to the variety of the quartet's patrons.

The principal agent in bringing them to Dartmouth was Peter Smith, director of the Hopkins Center, whose sensors seem to have picked them up as soon as they decided to "go public." (Only one member has Dartmouth connections. Jennings' brother Rix is a member of the Class of '67.) While they were still getting organized (and organizing a professional quartet must be as judicious and time-consuming a task as laying down a cellar of wine), Peter Smith brought them to Dartmouth for a short residency in the summer of 1971. The Friends of Hopkins Center have helped to support the quartet financially. The Music Department, therefore, is only one of the legitimate claimants for the Concords' time, and this arrangement permits a degree of independence which is highly valued and carefully guarded.

That said, however, it should also be said that the quartet teaches enthusiastically and, to inexpert eyes at least, very well. Its presence here has meant that the Music Department has been able to add instruction in viola and cello and has greatly increased the available offerings in violin, developments which should be inducements to future music majors. The coming and going of the Concords - they are already intercontinental concert artists - means that a complete term of instrumental teaching is never quite possible, but their willingness to juggle schedules and find time for their pupils shows personal commitment which is an invaluable compensation.

Mark Sokol was asked about the quality of his Dartmouth pupils: "Some pretty good fiddlers." And, indeed, fiddling seems to be on the increase, urged on by the quartet. The student Chamber Orchestra is to make its debut soon ("We go up and make speeches to them from time to time"), and more students than ever are playing in the Dartmouth Symphony, now striving hard to lose its reputation as the scourge of music lovers in the Upper Valley. A student last year gave as his excuse for some late work the fact that he had been testing his new bow. "Archery?" asked the professor. "Violin!" said the student. At least one student quartet has been playing together with the goal of a public performance, and if that is happily attained then the Concord Quartet's happiness is likely to be greatest of all.

Quartet players are famously fanatical and the Concords enjoy being so. They don't doubt that he deserves best of mankind who makes two string quartets grow where only one grew before, and some aspects of their own teaching harmonize with their ambition to spread the gospel of the quartet. In Summer Term 1975 the Concords combined with Stephen Ledbetter, assistant professor of music, to give a course on the history of the string quartet, a project for which they are already well equipped since their repertoire, like the history of the quartet, runs from Haydn up to works on which the ink isn't quite dry. When musician meets musicologist there is apt to be tension, since many musicians see musicologists as hopelessly impractical theorists, or worse. Ledbetter found, however, that he and the quartet shared many approaches to musical history and analysis. Though Sokol might growl that everything had been discussed except the weird mystery of this particular late Beethoven quartet, it was evident that however inadequate words seemed at times, the Concords liked talking about quartets only slightly less than playing them.

One musicologist and four string players add up to "team teaching," a form of instruction which can mean valuably divergent points of view or utter chaos - "four profs in search of a theme." The diversity in the case of one of their courses, Music 7, turned out to be mainly a matter of personalities. In talking about the music the Concords have a remarkably unified attitude, something, as Ledbetter points out, that is really their object in life. As personalities, the four are markedly different, but the fact is seen only rarely on the concert platform. Once, when they were poised to begin one of Webern's tiny and demanding Bagatelles, concentration was broken by the cry of a child. Fischer laughed, Kochanowski seemed bemused, Jennings smiled, and Sokol glared like Herod.

When Music 7 entered the ultra-modern reaches of the quartet's repertoire - Cage, Crumb, Hiller, Rochberg - the adjunct professors found themselves mediating between a frequently bewildered class of students and composers whose intentions were not always visible to the performers. They managed to combine fidelity to the composer's sometimes startling instructions with a professional's appreciation of the possible, never letting go of a critical sense of humor. George Crumb's BlackAngels, for Electric String Quartet calls for contact microphones attached to the instruments' bridges and plugged into a bass amplifier, plus tongue clicks and the shouting of numbers in various languages. The Concords describe one part as "the amplification of a mosquito in a shower stall with several multi-lingual karate experts trying to swat it." John Kochanowski recalls phoning the composer during recording rehearsals to ask if the volume of sound was really to rise to the level of pain. "He said 'Yes,' " and it does. It makes terrific competition for the Grateful Dead, and whatever critical view the quartet may have of it, they recorded it with scrupulous affection. (Vox SVBX-5306 if you'd like to try it on the neighbors.)

Talking about quartets and giving a course aren't exactly conterminous, however, and like many artist-teachers the Concords find it a little odd to be giving grades to students. But they have no doubts about the need to talk about the music they play, for they know they must work to create their own audience. They know, too, that teaching is a performing art, and in conversation they discuss the course they gave much as if it were a concert - and it will always be better next time. Next time will be a course on the complete Beethoven quartets, to go along with their concert series.

Mark Sokol

Andrew Jennings

Norman Fischer

John Kochanowski

An Englishman educated at Oxford, DavidWykes joined the Dartmouth faculty in1972 and teaches courses in Englishliterature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

October 1975 By WILLIAM J. MONTGOMERY, STEPHEN R. PARKHURST

DAVID WYKES

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

JUNE 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOTHER OF ALL RANKINGS

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

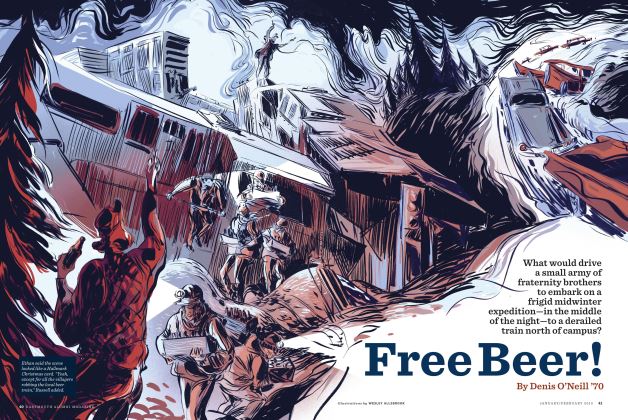

FeatureFree Beer!

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Denis O'Neill ’70 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNo Script Required

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60