In the May issue Warner Traynham '57,who was a black student "before therevolution" and now is dean of the TuckerFoundation, examined the current state ofblack and white at Dartmouth. This articlelooks backward to the ferment of the late1960s when for blacks at the College "thetaste of life became bittersweet." Theauthors lived through that time and, withsome of their contemporaries, reflect hereon what it meant for them personally.Albert Moncure '69 is an associate with aNew York law firm and Ronald Neal '69 isa graduate student in Chicago who plans toattend medical school next year.

"You who did not live before the revolution do not know what the sweetness of life was like" - Talleyrand's famous remark uttered after the French Revolution is the inspiration for Bertoluccl's film, Before the Revolution. The film concerns a well-to-do but socially conscious young man in modern France, who, deeply troubled by conditions in his county, searches vainly for a solution to society's ills and for an answer to the moral and philosophical questions plaguing him. The young man concludes unhappily that for the sons of the bourgeoisie, like himself, it is always "before the revolution." So, too, for the majority of the black students who attended Dartmouth during the latter half of the last decade it was "before the revolution" - for many, it still is.

Of course, Talleyrand's comment and the young man's conclusion are ironic. If life before the French Revolution was sweet, it was so only for a privileged few. And the flavor of existence for the privileged protagonist in Bertolucci's film is more accurately described as bittersweet - bitter because of his awareness of the social and economic plight facing many of his countrymen, sweet because society has spared him from that plight. Indeed, it has afforded him numerous benefits, not the least of which is the luxury of being able to sit back and intellectualize about how best to re-order society. Radical theories of revolution and helpful hints for the better ordering of the universe are, after all, preoccupations of the middle class intelligentsia. The poor, who must eke out an existence, seldom have time for such lofty pursuits.

For the black students who entered Dartmouth during the mid-1960s - before the revolution - the taste of life became bittersweet as the civil rights movement gained in intenstity. To be sure, the movement by then had precipitously changed its locale from rural hotbeds of racism, the launching pad for civil rights activism, to college campuses both North and South, where the cry was heard for a new type of leadership. The call was for Black Power.

At Dartmouth, black awareness and collective action arose spontaneously to meet the growing demands of the minority student body. By April of 1966, the Afro-American Society had been formed, still another manifestation of the neccessity for making life at an Ivy League college relevant (to unearth a seldom under-used term of those years) to events erupting throughout the urban centers of the United States.

And relevancy there was on the Dartmouth campus in those years. In the spring of 1967, a number of students, led by black undergraduates, united to challenge the College's investment policies. A sit-in took place in President Dickey's office to dramatize demands that the College vote its large block of Kodak stock in favor of shareholder proposals sponsored by FIGHT, a Rochester-based community action organization. Later that spring hundreds of Dartmouth students, again led by black undergraduates, vociferously protested the presence in Hanover of George Wallace, who had come to speak in support of his presidential candidacy. And finally in the spring of 1969 there was the momentous confrontation between the College administration and black students seeking a wide range of reforms including substantially increased minority admissions.

MOST of the black students of that era saw such activities as mere preliminaries, as a prelude to the day when they would graduate and "return to the community." That well-intentioned but somewhat ill-defined notion was the central tenet of the faith of those days. It mattered not that many of the black students were not even from the "community" to which they sought to return, that many were from solidly middle-class backgrounds. "Return to the community" was simply a phrase which most equated with an obligation to use their talents in a socially responsible manner.

As it turned out, not many of those students actually did return to the community, at least not in the literal sense. A handful has worked in black communities in various capacities and for varying lengths of time. While one graduate, from a small Central American country, returned to his native land to become a real revolutionary, a professional anti-fascist who has been tried for sedition and otherwise persecuted and harrassed by a repressive government for his efforts, only one or two former students have engaged in similar activities on the domestic front. And their efforts have appeared more comic than heroic, more pathetic than tragic. By and large, most of the black Dartmouth graduates of the civil rights era are now thoroughly settled in the Establishment.

Some insight as to why more black graduates did not return to the community comes from someone who did - Woody Lee. Lee, a member of the Class of 1968 who was elected to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior and who served as chairman of the Afro-American Society for the first two years of its existence, chose not to cash in on his academic credentials. Instead of seeking a lucrative job or applying for prestigious post-graduate fellowships, he decided to work within the confines of urban blight, in the poverty stricken ghetto areas of Jersey City and Harlem. For seven years he worked as a community organizer and urban planner for a variety of community groups and social reform organizations. Despite this record of active participation in the black community, Lee does not believe that such endeavors have significant, long-range impact on improving conditions for Afro-Americans. He laments that for a number of reasons "the situation in society conspired to frustrate what we wanted to do back in the days when we were at Dartmouth."

Specifically, Lee bemoans the lack of institutions through which college-educated blacks can contribute to the development of society by working directly within the black community. He feels that in general the opportunities for black graduates to obtain purposeful work within a ghetto are severely limited, although he points out that he has been able to find a number of socially oriented positions largely through his own tenacity and determination. Lee concludes that a major shortcoming in the way his black contemporaries viewed the world is that in proclaiming the virtues of returning to the community, they failed realistically to analyze what they actually could do within the community.

Another problem Lee sees with the ideal of "returning" is that a number of black graduates attempting to work in ghetto areas have found themselves unable to cope emotionally with the inner city problems they faced, either as a result of being insensitive or patronizing or simply because they lacked the temperament needed to function effectively within a black community. He says that such work demands a unique set of personality traits combining just the right sensitivity to the needs of the poor and the detachment required to formulate objective solutions to their problems. Although Lee feels the requisite temperament can come from experience and training, he again points to the lack of institutions which can provide education.

Despite his skepticism that blacks can effect significant social change by returning to the community, Lee retains a positive feeling about his work of the past seven years, based mainly on new friendships and lessons learned about dealing with people. Moreover, he strongly believes that all black graduates, regardless of their ultimate professional goals, should spend at least two years working within a ghetto community, not necessarily for the contribution they can make toward improving life within the community, but simply for the immensely valuable personal rewards to be gained from the experience.

THAT most black graduates have never returned to the community is probably attributable ultimately to the desire to succeed professionally, a desire which for many simply could not be fulfilled by working in a ghetto. Success in traditional terms was a value which most black students of the late sixties openly rejected, like their white activist counterparts. But some no doubt secretly longed for it even then, and many have since come to embrace it wholeheartedly.

For one thing, black graduates have come to realize that real power is wielded by individuals in positions of prominence and influence within industry and government. Also, it simply does not make good sense to exclude themselves voluntarily from positions from which their forebears had been barred forcibly for hundreds of years. This viewpoint is not shared by many of the white activists of the sixties. One of them, now a legal services lawyer in Boston, who, when told a particularly radical black student at Dartmouth was now working as an investment adviser on the West Coast, observed with dismay, "That's really a shame."

The current difference of opinion between former black and white activists is not surprising. Perhaps because access to positions of power and influence had always been assured to white students who wished to avail themselves of such opportunities, it was easy for them to reject such options. But for black students, who could never take entry into the mainstream of American life for granted, success in the traditional sense remained an aspiration to be valued.

Moreover, black students always viewed the world in more realistic terms than did their white activist counterparts whom they admired and with whom they occasionally formed uneasy alliances, but whom they never completely trusted. Woody Lee recalls asking a white Barnard alumna who had been involved in the 1968 student uprising at Columbia what she and and her fellow students actually thought they were accomplishing at the time. She responded that "we thought that the revolution had come." While black students at Dartmouth during the sixties may have viewed the world somewhat romantically, they were not so naive as to believe that the revolution was imminent and that everything traditionally valued by American society should be abandoned forever on the "scrap heap of history."

Many blacks also have become attracted to success out of an acute need for intellectual gratification. Woody Lee, for example, confesses that perhaps his major disappointment with his work of the past seven years is that "there weren't the opportunities for advancement, to see oneself moving ahead; there just weren't the opportunities to do one's best." Lee recently left the Harlem community to attend Yale Medical School, and although he does not want to be "burdened" with the idea of having to return to Harlem once he finishes medical school, he feels that whatever he does, it will be in "some form of public service."

RICK Porter '70, a corporate lawyer with a large Milwaukee law firm, shares Lee's present desire to succeed, but in large part because he feels that success achieved by individual blacks may have a significant impact on the black community as a whole. Porter cautions, however, that "the jury is still out with regard to the performance of our classes. Whether our personal success can be translated into something of long-range value for the black community as a whole ... still remains to be seen." Porter fears that certain of his contemporaries may become "co-opted" once they achieve success or become, as he puts it, "niggers sitting by the door" - successful blacks who are less than fully responsive to the needs of their brothers. But he notes that "we have resisted the argument heard so often in our college years that merely to be where we are is per se an acceptance of co-option." And he feels this is a good sign.

Porter's own professional accomplishments seem to belie his doubts that blacks of his generation can achieve professional distinction without betraying their ideals. Porter, like Lee, was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and an extremely active member of the Afro-American Society. He graduated from Dartmouth in three years, earned a law degree from Yale in 1972, and since then has managed to involve himself in a wide range of socially useful activities while pursuing a career in corporate law.

Recently he represented a black director of the Opportunities Industrial Center of Milwaukee in connection with a suit to set aside an improperly conducted election. He has represented the Urban League in legal negotiations and helped to start the first apprenticeship program in Wisconsin involving unions, lawyers, and civil rights groups. The program is attempting to place a substantial number of women and minority group members in high-paying jobs in the.construction industry, jobs from which they have previously been almost completely excluded. Porter's firm also represents the only black bank in Milwaukee.

Porter has also managed to distinguish himself in areas unrelated to civil rights. During the Watergate era, he served for six months as counsel on the special impeachment inquiry of the House Judiciary Committee and wrote the brief for the winning side in a landmark securities case decided by the Supreme Court several months ago.

Despite the apparent contradiction between personal aspirations and the necessity for social commitment - a contradiction which many readily acknowledge - most black graduates of the late sixties still feel, as Porter's activities suggest, a deep sense of devotion to many of the underlying values which they held as students. The persistence of those beliefs is likely attributable to the intensity of the experiences which produced them in the first place. Woody Lee notes that many of the values held by black students during the sixties originated with those students themselves as a result of intense selfexamination engendered in response to events taking place in the larger society. He recalls that "many of the ideas and positions that we committed ourselves to were derived out of our own thoughts, discussions, and interaction. These ideas were not simply 'hand-me-downs' from older students. We had to figure out a lot of things for ourselves in those days - where we would stand on a number of controversial issues, how we would deal with the administration, how we would relate to the other students."

Likewise, Bill McCurine '69, now a corporate lawyer on the West Coast, who was Lee's successor as chairman of the Afro-American Society as well as a Rhodes Scholar, remembers that "the atmosphere at Dartmouth was so highly charged politically that you were forced to think about the issues. Because we had to wrestle with questions about identity and commitment, these beliefs have tended to last." Words such as "commitment" and "involvement," which succeeding generations of students have come to view as tired platitudes, were fresh and exciting concepts to black students in the sixties.

THE self-examination and group interaction which helped produce such values and caused them to persist was possible largely because of the unique sense of community which existed among black Dartmouth students of that era. It was unique because it did not exist before those students came to Hanover and has not existed since they left. A black member of the Class of 1958 recalls that when he was a student "blacks tended to go their separate ways," while Eileen Cave, a member of the Class of 1976, observes that despite the relatively large number of black students at Dartmouth today, there does not appear to be a clearly identifiable, closely-knit black community in Hanover.

During the sixties, a genuine sense of community did exist among black students, engendered not by a need to reinforce one another academically or socially ut out of a shared concern for the problems of black people in the larger society. Bill McCurine comments that

our experience at Dartmouth was an expansive one. Our blackness was not a hole into which we burrowed to escape the problems of racism in the society or the pressing questions about identity. Quite the contrary. The intense concern for black people in this country galvanized us into a greater sense of the need to act in a responsible way. During those four years, brothers became more involved in a wider spectrum of activities than ever before. And with this came a new-found sense of importance, a sense that what one did mattered in the great scheme of things. There was very little of the feeling that the individual was too small to change things. In fact, I keenly remember being charged with the notion that I could not only change things but that I had a responsibility to do so.

we are on our way to better things. I have a great deal of faith in the goodness, intelligence, and strength of our people." McCurine adds that the friendship, unity and camaraderie which existed among black students at Dartmouth during those years helped instill in him a sense of "infinite possibility," a feeling that together "we could conquer the world." His future plans range from an entry into black capitalism to a possible venture into politics, and he remains optimistic: "I am not depressed with the future of our people. Needless to say, so very much remains to be done. Only the tip of the iceberg has been uncovered. But I feel that as a people

In addition to the sense of community then prevalent, a relationship existed among black students, the faculty, and the administration that was conducive to the development of many of the ideas then held by the blacks. For example, Woody Lee recalls an organizational meeting of the Afro-American Society at which Richard Unsworth, former dean of the Tucker Foundation, helped the students analyze the pros and cons of a number of sensitive and complex issues without in any way imposing his views.

Although an adversary relationship frequently existed between the administration and black students, a mutual feeling of respect for differing viewpoints sincerely held also usually existed. Even during periods of intense confrontation, reason and restraint often prevailed. Black student demands in 1969 were resolved peacefully through the process of reasoned negotiation, while those of white student activists resulted in the take-over of Parkhurst Hall.

Wally Ford '70, outspoken campus activist, frequent critic of the administration, and one of the chief negotiators for black students during the 1969 confrontation, recalls that despite his differences with the administration, he "never really thought the College administrators were bad people." They "simply lacked the ability to perceive remedies to the problems with which they were faced." Ford credits his dealings with the administration as giving him valuable exposure to practical politics and providing him with experience in relating to people with whom he does not necessarily always agree. As a result, Ford, who is perhaps best remembered by fellow Dartmouth students for his declaration of war against white America delivered over WDCR following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., has apparently long since made a separate peace - or at least has declared a temporary truce. Now an aggressive trial attorney, he counts among his many activities membership in the Dartmouth Alumni Association of New York, of which he is a vice president.

ARE the graduates of the volatile period of the sixties a qualitatively new force, or are they merely representative of their predecessors? To be sure, it is readily apparent that blacks of the sixties have in certain respects followed their predecessors into the professions of law and medicine. But recent graduates reject the viewpoint that their careers have in any way affected their outlook or par- ticipation in the liberation of black people. They contend that today the road to social involvement must be traveled by way of individual success and stability.

Is their asserted moral superiority justified or is it merely an illusion insulating them from a harsh reality they choose not to face? Ever since the days of the Harlem Renaissance, there have always been certain enlightened young Afro-Americans who have been imbued with the messianic hope that they would lead black people into the promised land of social progress and economic self-sufficiency. Yet these goals remain to be realized. Rick Porter's admonition to take a wait-and-see attitude will no doubt find little argument from those who are objective about this question. It is still too early to draw a firm conclusion, it is still "before the revolution." On the other hand, it cannot be denied that the black man of today is, in certain fundamental ways, different from his counterpart of 20 or 50 years ago. If black students hungered covertly for success in the sixties, so also did they thirst - openly - for a sense of moral purpose and direction, for meaning to their own identities, and for a code of behavior around which they could structure their lives. Today many of those former students are struggling to live their lives according to those rules. Fundamental change in the social fabric of this society remains an elusive goal for the majority of Afro-Americans, but if these concerned young black men of Dartmouth are true to their ideals, the struggle will not be heard as a Vox Clamantis in Deserto.

Detail from a mural by Florian Jenkins, Dartmouth Afro-American Center.

Detail from a mural by Florian Jenkins, Dartmouth Afro-American Center.

"Our experience was expansive ... what onedid mattered in the great scheme of things."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

October 1975 By WILLIAM J. MONTGOMERY, STEPHEN R. PARKHURST

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBronx County Chairman

APRIL 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOUTING CLUB PIN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

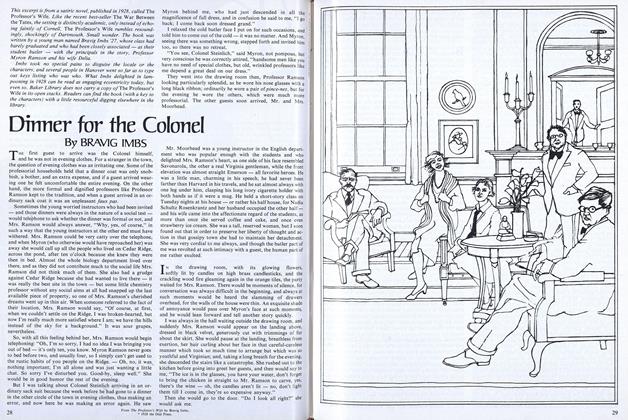

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureLove and War Among the Ivies

Jan/Feb 1981 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureBack to the Source

MAY 1983 By Matt Haley '83