IN mid-October the author, an associate professorof English, joined History Professor Jere Daniell '55 at a two-day Dartmouth Seminar in the foothills of the Berkshires. Thiswas the fifth annual seminar for alumni on the theme of "TheNature of New England' (some eight or ten similar sessions areheld around the country annually), and this time the faculty discussed small-town and rural New England in the period after theCivil War; the decline of New England as an economic andcultural center and its effect on the literature produced by such"regionalists" as Frost, Dickinson, Robinson, Wharton, andMetalious (Grace).The responses of the participants, says Professor Cook,ranged from resentment at what was perceived to be an assaulton the image of 'the crusty Yankee farmer' and the 'white nun ofAmherst' to delight in finding poets who were a reflection of realNew England life, who wrote of specific deaths rather thanDEA TH, the realities of a declining economy rather thanDECLINE. This view of the darker side of the poets certainlydisturbed those readers who had cherished the poets as proof thatmost modern poetry in its obsession with tragedy and failure, its'violation of the rules of poetry,' was way off base. In short, itwas an exciting exchange, one which I look forward torepeating."

He seems to say the reason why so much Should come to nothing must be fairly faced.

"Pod of Milkweed," Robert Frost

REGIONALIST" has so often been used to mean secondrate or limited in artistic appeal that it amounts to something like heresy to apply the term to a writer who has been admitted to the ranks of the great or near-great. Rather than slap such a restrictive label on the artist, we must show how he is anything but regional - tied to a specific geographical region and its traditions - for in the view of some critics and readers, to be regional is to miss the artist's proper function: universality. Knowing that any writer worth his salt deals with the human conditions we tend to ignore those aspects of his work that are tied to particular human conditions. Like many of the critics who have written on Robert Frost, we belabor the obvious: we argue that although he spoke of the particular landscape, customs and beliefs of New England, he was presenting a world in miniature. The most serious difficulty with this approach to the artist is that it makes it too easy to give short shrift to the specifics of his work and to dwell at great length instead on the broader implications of the images he presents.

Our central question is how did the poetry of Robert Frost, Edwin Arlington Robinson, and Emily Dickinson reflect New England small-town life? How was that literature a product of the soil and history of the hill country? Here I will deal with the specifics, believing that if they are clearly and closely examined the "universals" will take care of themselves.

Professor Daniell describes the years from 1790 to 1830 as a peak period in the economy of New England. This time of relative prosperity was followed by an economic decline in the hill country which lasted roughly until the turn of the century, and was marked by a gradual decline in agriculture (in 1864, 12 million acres were in cultivation; 50 years later, seven million), dwindling fish and game, deforestation of wooded areas (in 1875 forests covered half as many acres as they do today), absence of second-growth trees, exhaustion of the land, competition from the Midwest for the grain and whiskey market, competition for jobs by immigrants from southern Europe.

Some of the results of these conditions were a loss in the religious unity that had existed prior to the influx of large numbers of Roman Catholics, fragmentation of a fairly uniform ethnic population, a loss of population in most of the towns between 1870 and 1900, abandoned farms, inbreeding, poor diet and excessive drinking. The migration of young people to the larger towns where industry and jobs were centered left in its wake the old, the hopeless, and especially the spinster who became such a central figure in New England mythology. The influx of new people, who in many instances threatened the resident Yankee's domination of the labor market and the Protestant unity of the area, bred a distrust of outsiders, the establishment of ethnic ghettos and a rigid caste system. The preoccupation with caste, the recital of genealogies, the triumph of the shrewd Yankee over the outsider, the doctor, minister, spinster, the eccentric, the grasping newly-arrived businessman, the drunk and the idiot - all these were features that distinguished the literature of decline.

In order to live with the "diminished thing" that was his way of life, the New Englander developed a mythology of failure. There was something worthy of respect in not being part of the economic boom. That was for the crass money grubbers. The Yankee looked back to another period, the period before the decline, and made a gospel of the toughness which a life spent in struggle with a harsh, unyielding land 'demanded. He began to worship his "queerness."

So we come to Emily Dickinson, Edwin Arlington Robinson, and Robert Frost - poets of New England in decline. Dickinson's Amherst was not the home of Puritanism in its most glorious day; it was the last bastion of a fading ethic. Robinson's Gardiner, Maine was a dying mill town, and Frost's hill country New Hampshire was not a bucolic "Barcan wilderness" but a harsh, desolate foe. The artists who described this New England were very much the children of the New England past - heirs to a great tradition now dimmed - bewildered infants trying to spell God with the wrong blocks - singers learning in singing not to sing.

Consider Dickinson's treatment of the broadside elegy, that poem written on the occasion of death and intended both to console the mourning family and to comment on the universal truths to be found in that death. Although Dickinson, like 17th century poet Anne Bradstreet, wrote broadside elegies, her focus is not on the orthodox Puritan interpretation of the death she laments. Note the difference in the closing lines of Bradstreet's poem "In Memory of My Dear Grand-child Elizabeth Bradstreet, Who Deceased August 1665 Being a Year and Half Old":

In nature Trees do rot when they are grown.

And Plumbs and Apples throughly ripe do fall, And Corn and grass are in their season mown, And time brings down what is both strong and tall.

But plants new set to be eradicate, And buds new blown, to have so short a date, Is by his hand alone that guides nature and fate.

and Dickinson's elegy on the death of Laura Dickey:

She mentioned, and forgot; Then lightly as a reed Bent to the water, shivered scarce, Consented and was dead.

And we, we placed the hair, And drew the head erect; And then an awful leisure was, Our faith to regulate.

There may be in the works of Dickinson the traditional Puritan broadside elegies, the poems of providential mercy or disaster, the dedicatory poem, the meditation, the valentines and the poems of trial and purification through suffering, but in most instances she makes her poems unique by refusing to adopt whole either the buoyant optimism of the transcendental view or the oppressive fatalism of her Puritan forebears. She may use the old theme of transcendence through suffering, she may employ the traditional hymn meters in many of her poems, but she puts on all these the mark of her individual personality. She is the poet of Amherst during the decline of the Puritan tradition, but she does not trade this system of belief for the Romantic Idealism of Emerson and Thoreau. Rather, she forges out of her experience a view that is in some sense a wedding of the two traditions.

Edwin Arlington Robinson, according to critic Yvor Winters, was a belated and attenuated example of the kind of New Englander in whom ingenuity has become a form of eccentricity. "When you encounter a gentleman of this breed," says Winters, "you cannot avoid the feeling that he may at any moment sit down on the rug and begin inventing a watch or a conundrum. ... Robinson is a specimen of the ingenious Yankee become whimsical."

The failures who live in Robinson's Tilbury Town are the New Englanders described in the first part of this essay: men like Eben Flood who have lived past the days of friendship and glory; men like Cliff Klingenhagen who, despairing of the good things in life, prepare themselves for the bitterness; men like Captain Craig in whom the vital spark is "choked under, like a jest in Holy Writ." The most important question for them is not how one might triumph; this is not possible. What one must learn in the diminished world of Robinson is how to bear life in all its hardness and at the same time retain some belief that goodness is possible beyond the darkness.

Like Robinson, Frost speaks of New England in decline. He is, according to Malcolm Cowley, "not the poet of New England in its great days, or in its late nineteenth century decline (except in some of his earlier poems), rather he is a poet who celebrates the diminished but prosperous and self-respecting New England of the tourist home and the antique shop in the abandoned grist mill."

There are some serious weaknesses in Cowley's analysis, but it is not necessary here to argue them. It should be noted that Frost's failure to give equal time to the Poles and French Canadians who lived in the region about which he wrote and with whom Cowley feels he should have been concerned, is a mark of the distrust of the newcomer that characterizes the literature of small-town New England. Further explanation may be found in Frost's own concern with what he called synecdoche: the part for the whole. He wrote about particular men in order to speak to the condition of all men. In the same sense, he ignored in most of his poetry the large towns, the factories, railroads and radios that were a part of the landscape. Frost carved out a specific territory for himself and it was with this territory that he was concerned for most of his life as an artist. Like many of his characters, his poetry was defensive - behind the mask of the crusty Yankee he was free from interference and possibly from undesirable influence.

Frost's ties with earlier New England literature are clear from his selection of Longfellow's poem about diminished possibility as the source for the title of his first published collection of Poetry. Like Dickinson, however, he was not of the world inhabited by Longfellow, Emerson or Thoreau and so although he may have dealt with similar subjects and themes, his voice and attitude were different. To Frost, Emerson's "Brahma" is not a Poem of triumph for the lover of the good. "War is the natural state of man - remember what Emerson said about nature being red in tooth and claw." He takes issue in "New Hampshire" with the Emerson of "Ode" - the poet as social critic and reformer. His "Ovenbird" and "The Quest of the Purple Fringe" have little in common with Bryant's "To the Fringed Gentian" even though the image of the bird and that of the flower are used in both. Bryant ends what is in the main a descriptive poem with a "transcendent truth" -

I would that thus, when I shall see The hour of death draw near to me, Hope, blossoming within my heart, May look to heaven as I depart.

Frost comes from his observation of the flower not with "a great clarification, such as sects and cults are founded on" but a less resounding awareness

I only knelt and putting the boughs aside Looked, or at most Counted them all to the buds in the copse's depth That were pale as a ghost.

Then I arose and silently wandered home, And I for one Said that the fall might come and whirl of leaves, For summer was done.

The New England of Robert Frost, the "diminished thing," was not something about which one could sing songs of praise and transcendence. It was a land whose harshness demanded that one develop toughness, coldness and detachment if one hoped to survive. One must "Take something like a star," be separate, keep cold, take one step backward "out of all this now too much for us." It was not the land which Berkeley saw in 1726

Not such as Europe breeds in her decay; Such as she bred when fresh and young When heavenly flame did animate her clay By future poets shall be sung.

Westward the course of Empire takes its way; The first four acts already past, A fifth shall close the drama with the day; Time's noblest offspring is the last.

or the land prophesied by Brackenridge and Freneau in their commencement poem

Paradise anew Shall flourish, by no second Adam lost, No dangerous tree with deadly fruit shall groan, No tempting serpent to allure the soul From native innocence. - A Canaan here, Another Canaan shall excel the old.

or the land Thomas Tillam saw in 1638

Hayle holy-land wherein our holy lord Hath planted his most true and holy word Hayle happye people who have dispossest Yourselves of friends, and meanes, to find some rest.

These are springtime poems while the personae who inhabit the world of Dickinson, Robinson, and Frost live in another season: "the fall we name the fall." In this season of loss, "children learn to walk on frozen toes." Here we are rarely presented images of abundance or light. Rather we have Calvary and New Hampshire - a state with nothing in abundance, nothing in commercial quantities except writing and that won't sell. It is a restful and desirable state because it is deficient; a world of retreat whether that retreat is toward the star or toward a stream too "lofty and original to rage"; a state where we pull in our ladder and put up a sign forbidding anyone else to enter our secure hole. It is a world of retreat in which we avoid the corrupting influence of the world by relinquishing contact with it and its vulgar pleasures. We become nobody instead of somebody. We select once and then refuse to be drawn into the act of passionate contact again. We choose to wade in grief, to drink the wormwood - for the strength to live lies in this acceptance rather than in joy and wine. We are driven by life's coldness to a hill above Tilbury Town with only our jug for company and two moons listening; to the narrowest corner that is available.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

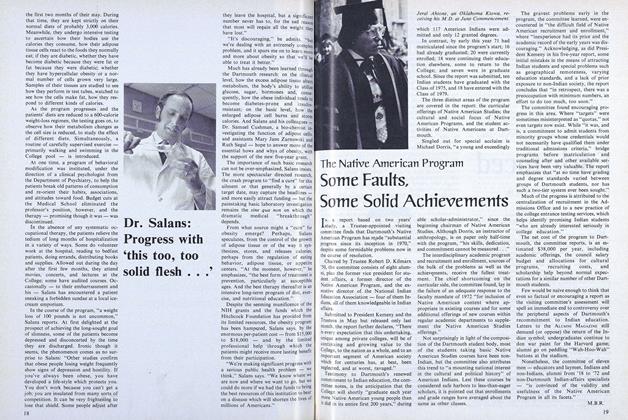

FeatureOBESITY

November 1975 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureSome Faults, Some Solid Achievements

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1975 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

November 1975 By RICHARD W. LIPPMAN, A. JAMES O'MARA -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

WILLIAM W. COOK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Harris Upham 1832

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1960 By Donald F. Sawyer '21 -

Feature

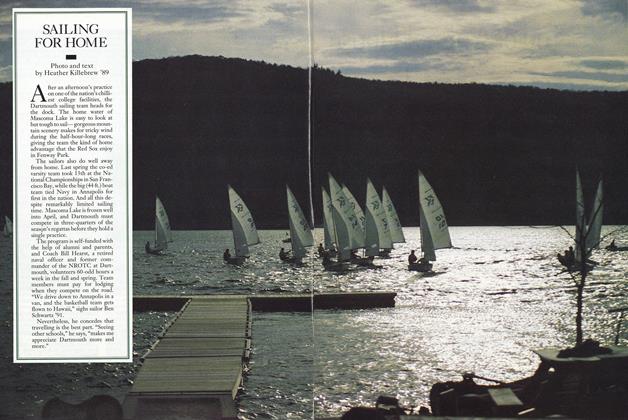

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeaturePeople of the Book

APRIL 1999 By Michael Loventhal '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

NOVEMBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96