The Native American Program

IN a report based on two years' study, a Trustee-appointed visiting committee finds that Dartmouth's Native American Program has made "substantial progress since its inception in 1970," despite some formidable problems now in the course of resolution.

Chaired by Trustee Robert D. Kilmarx '50, the committee consists of eight alumni, plus the former vice president for student affairs, a former director of the Native American Program, and the executive director of. the National Indian Education Association - four of them Indians, all of them knowledgeable in Indian affairs.

Submitted to President Kemeny and the Trustees in May but released only last month, the report further declares, "There is every expectation that this undertaking, unique among private colleges, will be of continuing and growing value to the College, to the nation as a whole, and to an important segment of American society which for centuries has, at best, been neglected, and at worst, ravaged."

Testimony to Dartmouth's renewed commitment to Indian education, the committee notes, is the anticipation that the College will shortly "graduate each year more Native American young people than it did in its entire first 200 years," during which 117 American Indians were admitted and only 12 granted degrees.

In contrast, by early this year 71 had matriculated since the program's start; 16 had already graduated; 20 were currently enrolled; 18 were continuing their education elsewhere, some to return to the College; and seven were in graduate school. Since the report was submitted, ten Indian students have graduated with the Class of 1975, and 18 have entered with the Class of 1979.

The three distinct areas of the program are covered in the report: the curricular offerings of Native American Studies; the cultural and social focus of Native American Programs, and the student activities of Native Americans at Dartmouth.

Singled out for special acclaim is Michael Dorris, "a young and exceedingly able scholar-administrator," since the beginning chairman of Native American Studies. Although Dorris, an instructor of anthropology, is on paper only half-time with the program, "his skills, dedication, and commitment cannot be measured . . ."

The interdisciplinary academic program and recruitment and enrollment, sources of the bulk of the problems as well as the achievements, receive the fullest treatment. The chief shortcoming on the curricular side, the committee found, lay in the failure of an adequate response to the faculty mandate of 1972 "for inclusion of Native American content where appropriate in existing courses and for some additional offerings of new courses within regular academic departments to supplement the Native American Studies offerings."

Not surprisingly in light of the composition of the Dartmouth student body, most of the students taking basic Native American Studies courses have been non-Indian, but the committee also attributes this trend to "a mounting national interest in the cultural and political history" of American Indians. Lest these courses be considered safe harbors to less-than-eager scholars, it is pointed out that enrollments and grade ranges have averaged about the same as other classes.

The gravest problems early in the program, the committee learned, were encountered in "the difficult field of Native American recruitment and enrollment," where "inexperience had its price and the academic record of the early years was discouraging." Acknowledging, as did President Kemeny in his five-year report, some initial mistakes in the means of attracting Indian students and special problems such as geographical remoteness, varying education standards, and a lack of prior exposure to non-Indian society, the report concludes that "in retrospect, there was a preoccupation with minimum numbers, an effort to do too much, too soon."

The committee found encouraging progress in this area. Where "targets" were sometimes misinterpreted as "quotas," not even targets now exist. While "it was, and is, a commitment to admit students from minority groups whose credentials would not necessarily have qualified them under traditional admissions criteria," bridge programs before matriculation and counseling after and other available services have been very valuable. The report emphasizes that "at no time have grading and degree standards varied between groups of Dartmouth students, nor has such a two-tier system ever been sought."

Much of the progress is attributed to the centralization of recruitment in the Admissions Office and to a new practice of the college entrance testing services, which helps identify promising Indian students "who are already interested seriously in college education."

The net cost of the program to Dartmouth, the committee reports, is an estimated $38,000 per year, including academic offerings, the council salary budget and allocations for cultural programs, recruiting costs, and scholarship help beyond normal expectations for a similar number of other Dartmouth students.

Few would be naive enough to think that even so factual or encouraging a report as the visiting committee's assessment will spell an immediate end to controversy over the peripheral aspects of Dartmouth's recommitment to Indian education. Letters to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE still demand (or oppose) the return of the Indian symbol; undergraduates continue to don war paint for the Harvard game; alumni go on peddling "Wah-Hoo-Wah" buttons at the stadium.

Nonetheless, the committee of eleven men - educators and laymen, Indians and non-Indians, alumni from '18 to '72 and non-Dartmouth Indian-affairs specialists - "is convinced of the validity and usefulness of the Native American Program in all its facets."

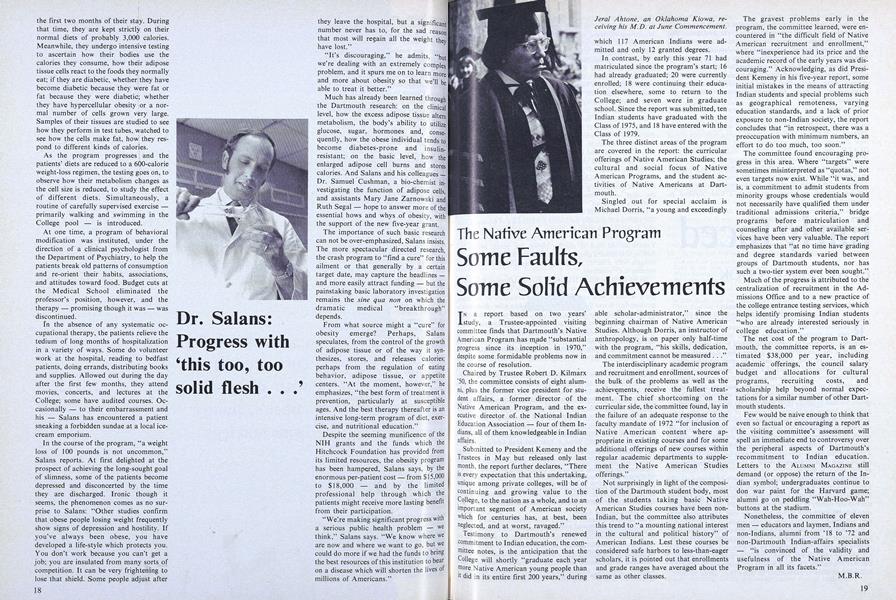

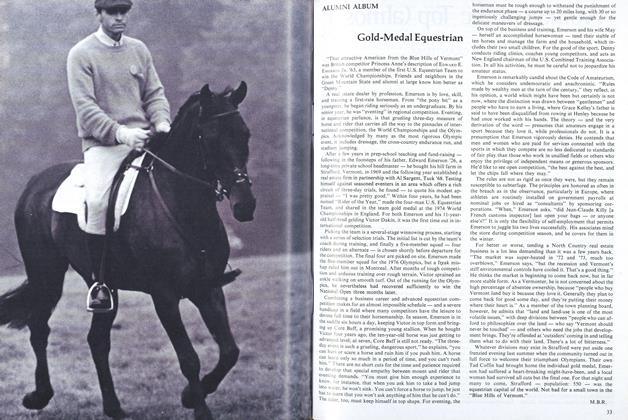

Jeral Ahtone, an Oklahoma Kiowa, receiving his M.D. at June Commencement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

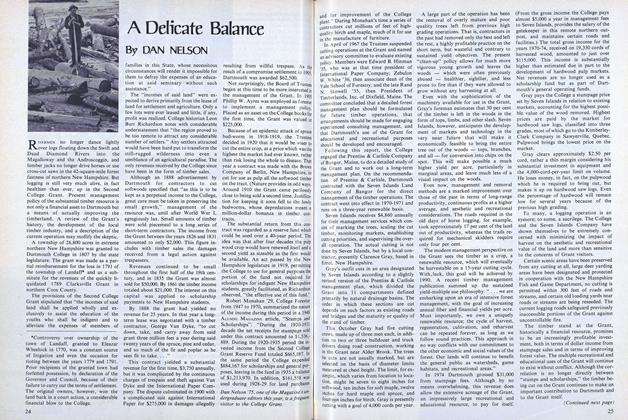

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

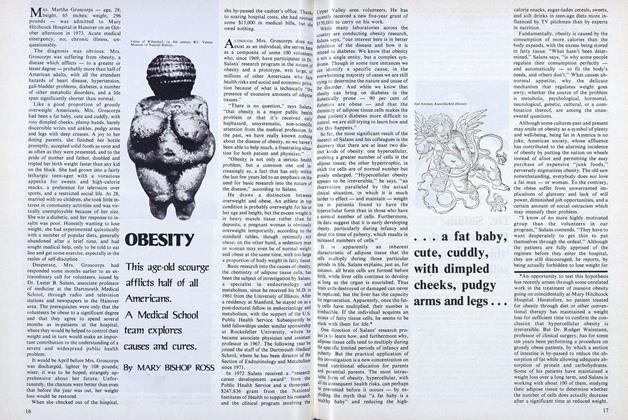

FeatureOBESITY

November 1975 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureFairly Faced

November 1975 By WILLIAM W. COOK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1975 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

November 1975 By RICHARD W. LIPPMAN, A. JAMES O'MARA -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureME Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDinesh D'Souza '83

March 1993 -

Feature

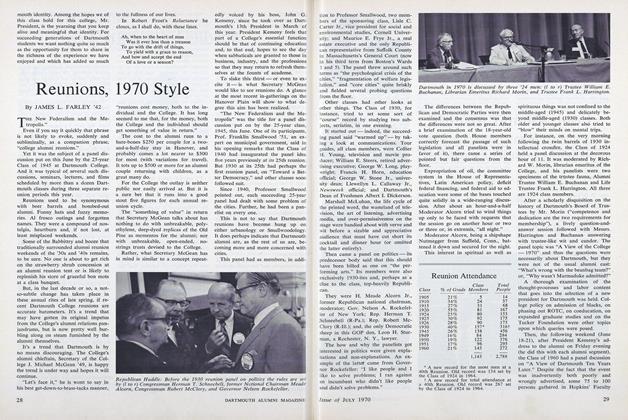

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

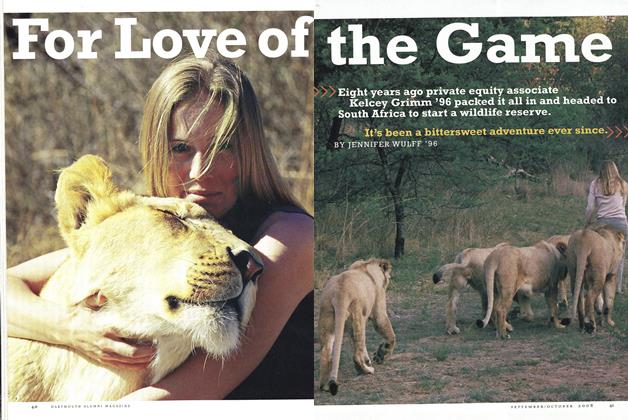

COVER STORY

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

Sept/Oct 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

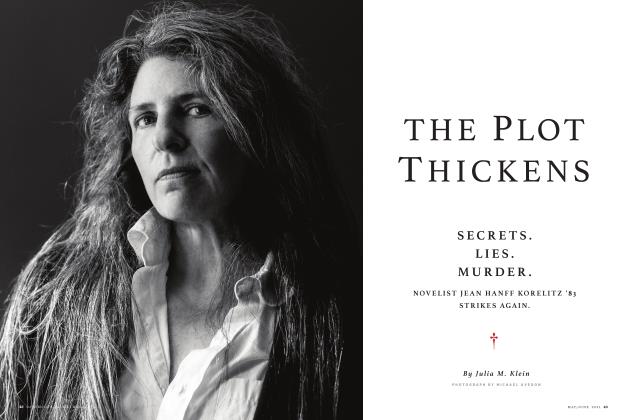

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Plot Thickens

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Julia M. Klein -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87