AT least half a dozen years before "Kung Fu" television star David Carradine began snatching deadly projectiles out of midair, the Dartmouth Karate Club was zeroing in on its first venerable opponents. And more than a quarter century before that, in 1939, the Big Green's original group of martial artists, the Dartmouth Fencing Club, was carving out an intercollegiate championship that has gone virtually unnoticed by posterity. Now, after years of slashing and bashing in relative obscurity, both fencing and karate have been promoted to the DCAC's roster of official varsity sports, both have become coeducational, and both seem to be on the threshold of a genuine renaissance.

The resurgence in fencing involves three main figures. Dartmouth-Hitchcock psychiatrist Michael S. Gaylor is a former Olympic fencer who was the volunteer coach of the Dartmouth Fencing Club, last year and was instrumental in getting it varsity status. Dale. K. Rodgers is another Olympic-level fencer and a former Columbia coach who came to Dartmouth this year, partly at Gaylor's urging, to become the fencing team's first full-time, salaried coach. And the real angel in the wings, Mrs. Patricia Hewitt of Moline, Illinois, is an official of the U.S. Modern Pentathlon Team who, with her husband William, chairman of John Deere and Co., this year agreed to underwrite the entire cost of Dartmouth's fencing program.

This isn't to say that everything is roses in Dartmouth fencing circles. With a 3-4 record in the North Atlantic Conference as of mid-February and with five more matches against generally tough eastern competition, the Dartmouth team will be hard pressed to break .500 this year. But Rodgers, a soft-spoken optimist, says the team now has the stability that makes building for the future more than just a consolatory euphemism for a losing season. "It takes three years before a fencer can even consider himself a competitor. We do have some talented fencers, and we're getting a lot of capable and enthusiastic newcomers from the physical education program. Right'now, of course, most of them are pretty, well, green. Anyway, we may lose more than we win this year, but we'll at least do it with class and style."

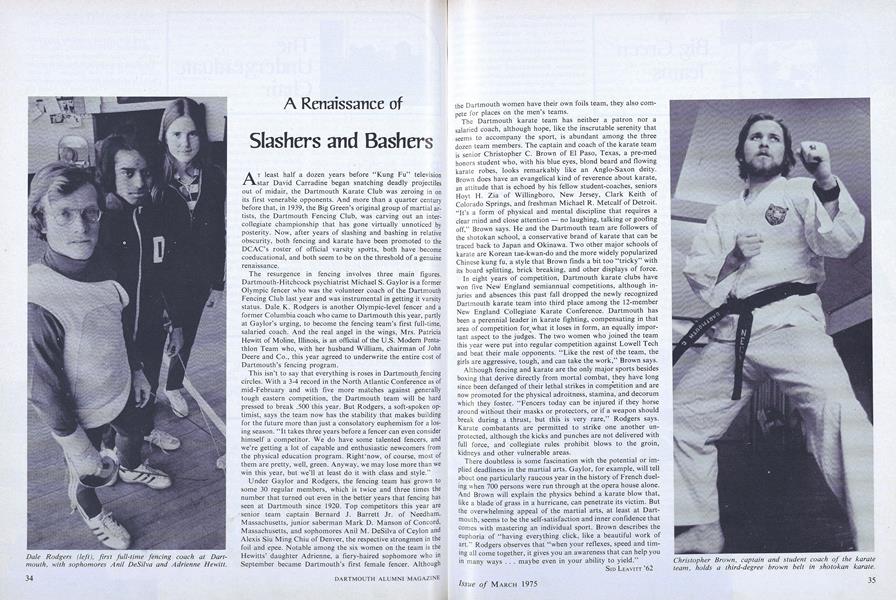

Under Gaylor and Rodgers, the fencing team has grown to some 30 regular members, which is twice and three times the number that turned out even in the better years that fencing has seen at Dartmouth since 1920. Top competitors this year are senior team captain Bernard J. Barrett Jr. of Needham, Massachusetts, junior saberman Mark D. Manson of Concord, Massachusetts, and sophomores Anil M. DeSilva of Ceylon and Alexis Siu Ming Chiu of Denver, the respective strongmen in the foil and epee. Notable among the six women on the team is the Hewitts' daughter Adrienne, a fiery-haired sophomore who in September became Dartmouth's first female fencer. Although the Dartmouth women have their own foils team, they also compete for places on the men's teams.

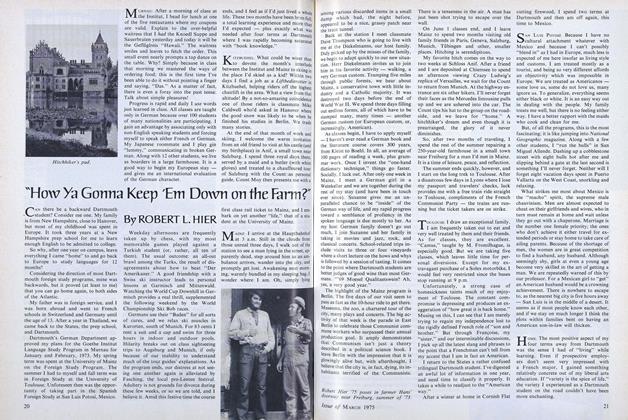

The Dartmouth karate team has neither a patron nor a salaried coach, although hope, like the inscrutable serenity that seems to accompany the sport, is abundant among the three dozen team members. The captain and coach of the karate team is senior Christopher C. Brown of El Paso, Texas, a pre-med honors student who, with his blue eyes, blond beard and flowing karate robes, looks remarkably like an Anglo-Saxon deity. Brown does have an evangelical kind of reverence about karate, an attitude that is echoed by his fellow student-coaches, seniors Hoyt H. Zia of Willingboro, New Jersey, Clark Keith of Colorado Springs, and freshman Michael R. Metcalf of Detroit. "It's a form of physical and mental discipline that requires a clear mind and close attention - no laughing, talking or goofing off," Brown says. He and the Dartmouth team are followers of the shotokan school, a conservative brand of karate that can be traced back to Japan and Okinawa. Two other major schools of karate are Korean tae-kwan-do and the more widely popularized Chinese kung fu, a style that Brown finds a bit too "tricky" with its board splitting, brick breaking, and other displays of force.

In eight years of competition, Dartmouth karate clubs have won five New England semiannual competitions, although injuries and absences this past fall dropped the newly recognized Dartmouth karate team into third place among the 12-member New England Collegiate Karate Conference. Dartmouth has been a perennial leader in karate fighting, compensating in that area of competition for what it loses in form, an equally important aspect to the judges. The two women who joined the team this year were put into regular competition against Lowell Tech and beat their male opponents. "Like the rest of the team, the girls are aggressive, tough, and can take the work," Brown says.

Although fencing and karate are the only major sports besides boxing that derive directly from mortal combat, they have long since been defanged of their lethal strikes in competition and are now promoted for the physical adroitness, stamina, and decorum which they foster. "Fencers today can be injured if they horse around without their masks or protectors, or if a weapon should break during a thrust, but this is very rare," Rodgers says. Karate combatants are permitted to strike one another unprotected, although the kicks and punches are not delivered with full force, and collegiate rules prohibit blows to the groin, kidneys and other vulnerable areas.

There doubtless is some fascination with the potential or implied deadliness in the martial arts. Gaylor, for example, will tell about one particularly raucous year in the history of French dueling when 700 persons were run through at the opera house alone. And Brown will explain the physics behind a karate blow that, like a blade of grass in a hurricane, can penetrate its victim. But the overwhelming appeal of the martial arts, at least at Dartmouth, seems to be the self-satisfaction and inner confidence that comes with mastering an individual sport. Brown describes the euphoria of "having everything click, like a beautiful work of art." Rodgers observes that "when your reflexes, speed and timing all come together, it gives you an awareness that can help you in many ways . . . maybe even in your ability to yield."

Dale Rodgers (left), first full-time fencing coach at Dartmouth, with sophomores Anil DeSilva and Adrienne Hewitt.

Christopher Brown, captain and student coach of the karateteam, holds a third-degree brown belt in shotokan karate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Article

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleVox

March 1975 By HOWARD

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION 1958

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO DITCH YOUR WHEELS AND JAZZ UP YOUR SEX LIFE

Jan/Feb 2009 By CHRIS BALISH '88 -

Feature

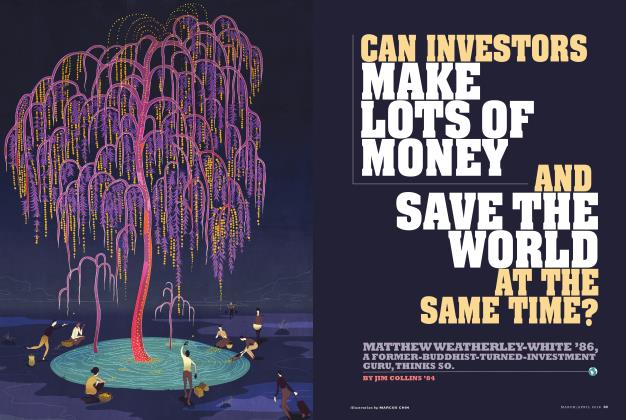

FeatureCan Investors Make Lots of Money and Save the World at the Same Time?

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureWarner's 41 Dramatic Years

MAY 1969 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureReady to Roll

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By RICK BEYER ’78 -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Who Designed the Center

MAY 1957 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45