Covert operations, inter-service rivalry, international agreements unimplemented, the subversion of unfriendly governments, undeclared wars and military advisers turned warriors, Arab blackmail, deniability. The tale of William Eaton's kismet has a familiar ring.

"To the shores of Tripoli." This phrase from the Marine Corps hymn evokes visions, if not of the massive invasion of Iwo Jima, at least of serried ranks of gallant, disciplined Leathernecks storming ashore to assault the bastions of the Arabian despots who, 175 years before the current embroglio, had the commerce of the western world - the infant United States included - tied in knots.

Gallant they were, and disciplined, but in reality the Marines who did battle "on the shores of Tripoli" in 1805 numbered precisely nine: Lieutenant P. N. O'Bannon, one midshipman, one sergeant, and six enlisted men. They were part of a ragtag army commanded by a self-appointed general, William Eaton of the Class of 1790, who marched across the African desert in one of the most bizarre chapters in U.S. military annals.

Eaton was a man given to extraordinary ventures and extraordinary roles. Before entering Dartmouth he narrowly missed action in the Revolution, having been dismissed ill from service by an army too poor to care for its' sick. The year after his graduation found him Clerk of the House of Delegates in the short-lived independent Republic of Vermont. He fought with Mad Anthony Wayne in Ohio, infiltrating the Miami tribe, so successfully that they accepted him as one of their own. He won the friendship of the Creek Indians on the border of the Spanish Floridas and the gratitude of white settlers for bringing peace to the area. He speculated in western land, parlaying $200 to $12,000, then to a fortune of $54,000. He undertook delicate espionage missions at the personal behest of the Secretary of State and of President John Adams.

"General Eaton," his stepson wrote after his death, "had a charm so great and a logic so persuasive that he could have talked Satan into abandoning hell and applying for a new post as a minor angel."

Out of a job in 1791, when. Vermont became the 14th state in the Union, Eaton declared: "Fame is a slow journey through the labyrinth of politics. Such a lot is not for me . . . Ere my candle sputters and dies . . . I must find myself a path to glory." In 1798, his Army service having proved only a detour, Eaton found his path to glory. Islam had long held a special fascination for him and he had become fluent in Arabic languages. Faced with the dreary alternative of retiring to Connecticut with his fortune - and a wife he loathed - he saw the Barbary States as his destiny, his Kismet, and requested appointment as Consular Agent in Tunis. President Adams, grateful for Eaton's discreet services, was happy to comply.

If Henry Kissinger finds the Arabs intransigent and the American people their individual and collective purses depleted in 1975, the problems are minor compared with what Consul Eaton faced. During George Washington's presidency, a sixth of the nation's annual budget went directly into tribute to the Barbary States: Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. Their pirates ranged as far as the North Sea, commandeering ships and cargoes, enslaving crews. As Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson had tried to form a cooperative, NATO-style protective force, but Congress refused to support it. Peace treaties, broken on whim, were purchased at the cost of delivering gold, silver, jewels, naval stores, and fully armed fighting ships dockside at North African ports.

Patience joined charm as one of Eaton's outstanding attributes, and he had need aplenty of both virtues in his dealings with the Bey of Tunis, albeit the most reasonable of the Barbary despots. His demands escalated as Eaton negotiated a new treaty: tribute must be paid in arms and ships, rather than cash, to carry on his war with France; he must have one barrel of gunpowder for each shot his guns fired in response to the elaborate salute he required of American ships entering his harbor; he would be pleased to accept, as token of the good faith of the President, an emerald ring the size of a gull's egg.

To Secretary of State James Madison, Eaton complained in 1802, "The indignities I have suffered at this court latterly, are insupportable .... The rich regalia I have already given the Bey . . . serve only to show him our wealth and our weakness, and to prompt his avarice to new demands. ... I am indeed weary of this state of exile and fruitless exertion. . . . Let me be supported or replaced." To the U. S. Minister in London, he wrote, "I am tempted to believe it is my kismet to treat these thieves with the contempt they deserve." He asked that his earnest request for a fleet of ships and 5,000 infantrymen and cavalrymen be conveyed to Washington. "With these troops and warships at my disposal, I can guarantee the President and the Congress that the rulers of the Barbary Coast will sing a new song, more to our liking." His deepest anguish was confided to his journal - and posterity:

Genius of my country! How art thou prostrate! Hast thou not yet one son whose soul revolts, whose nerves convulse, bloodvessels burst, and heart indignant swells, at thought of such debasement . . .? Shall Tunis also lift his thievish arm, smite our scarred cheek, then bid us kiss the rod! This is the price ofpeace! But if we shall have peace at such a price, recal me, and send a slave, accustomed to abasement, to represent the nation. And furnish ships of war, and funds, and slaves to his support, and our immortal shame. History shall tell that the United States first volunteered a ship of war, equipt, a carrier for a pirate. It is written. Nothing but blood can blot the impression out. I frankly own, I would have lost the peace, and been myself empaled rather than yield this concession. Will nothing rouse my country?

On official business in Tripoli in 1801, Eaton found the situation even worse: Bashaw Yusef Karamanli "a large, vulgar beast, with filthy fingernails" and a stench that made the consul ill."In New York he would have been a cutpurse hanged at the gallows; but such are the ways of Barbary that in Tripoli he was the master of the world."

The Bashaw had come to power by way of the murder of his eldest brother and the overthrow of Hamet Karamanli, the second of three sons. When the United States failed to meet his outrageous demands, he commenced stealing cargoes of American ships at anchor, had the flagpole at the consulate chopped down and the stars and stripes immersed in camel dung, and in May 1801 declared war on the U.S. Yusef's audacity emboldened the Bey of Tunis, who redoubled his demands, took to detaining American naval officers, and in early 1803 declared Eaton personna non grata. Eaton, sailed for home, to renew in person his repeated pleas for "American arms to force these brigand-kings to respect our nation."

Jefferson was preoccupied with final negotiations for the Louisiana Purchase, and neither he nor the War Department wished to commit troops to hostilities on land. Congress, instead of returning Tripoli's declaration of war, had given the President a free hand in deploying the Navy off Tripoli, in a move suggestive of the Tonkin Bay Resolution. The budgetminded Secretary of the Treasury, however, was trying to undermine the blockade. Meanwhile Eaton's uiquitous friends in high places persuaded the President to grant Eaton an audience, to hear his plan.

The plan, long germinating, was to find the deposed Hamet and restore him to power, thereby assuring the United States a friendly monarch in the strongest of the Barbary States. The President and Eaton met in private, and their agreement can only be inferred from a memorandum initialed by Jefferson authorizing an advance of $40,000 to Eaton "for use in restoring peaceful relations between the United States and Tripoli" and a statement signed by an Army colonel that "one thousand long rifles have been delivered to Mr. W. H. Eaton at the order of the Secretary of State." There can be little doubt that Jefferson knew Eaton planned the forceful deposition of Yusef, but the President may not have realized that the 39-year-old adventurer intended to lead the attack. Eaton was given the one-time title of "Naval Agent on the Barbary Coast," and it was understood that naval bombardment from the sea would coincide with the proposed attack on Derna, Tripoli's second largest city. If Eaton succeeded, the government would take credit; if he failed, he'd been entirely on his own. Everyone, from the President on down, preserved "deniability." It was only a Navy officer in Alexandria, concerned about Eaton's safety, who assigned the handful of Marines to escort him "to the shores of Tripoli."

In January of 1805, Eaton found the destitute Hamet in Egypt and persuaded him to take ostensible command of an army yet to be raised. Hamet would probably have preferred to be supported in sumptuous exile, but he had a few retainers, several wives, and many children to feed.

In Tunis, Eaton had learned Arab ways, as he had learned Indian ways in earlier days. He spoke four dialects fluently, was a superb horseman, and wielded his scimitar - made specially by a New York swordsmith — with the best of the Bedouins. "Like the little lizards one sees in one's garden here," he wrote in his diary, "I change my colors to match those of the land in which I reside. Once I was a Miami, then a Creek, and now I am something of an Arab.'" He had little trouble recruiting an estimated 500 to 700 Tripolitan Arabs who had fled Yusef's rule, about 100 Egyptians, and 50 to 200 Greek mercenaries, expert cavalrymen all.

Eaton's personal staff included his stepson, Eli Danielson, aide-de-camp throughout the African years; Dr. Mendrici, who was probably a baker's assistant rather than a physician; and the manservant Aletti, who, according to Eaton, "was born in Gibraltar, is free of London, a convict from Ireland, a burgomaster of Holland; was circumcised in Barbary; was a spy for the Devil among the Apostles at the feast of Pentacost, and has the gift of tongues; has traveled in all Europe, and will probably be hung in America, for I intend to take him there . . . the most useful scoundrel in the world." (Aletti, after Eaton's death, became Danielson's butler in Boston and allegedly begat a Professor of Latin at Harvard.)

Besides the Marines, the officers Eaton recruited to lead his motley army were a shady lot of rogues of dubious background. Leitensdorfer, the adjutant, purportedly an American military engineer, was an Austrian Army deserter, bigamist, international spy, pimp, and sometime Capuchin monk. Among the others were an "Englishman" with an Italian accent; a self-styled Bourbon refugee, possibly a bastard son of Marie Antoinette's chambermaid, who lapsed into Spanish under stress; and a Turkish army officer, whose fondness for the bottle separated him from the Mohammedan corps. With one exception, they were all fiercely loyal to Eaton.

The "enlisted men" had no such strong feelings, but Eaton had a talent for earning their respect. Shortly after the march began, to the blended tones of Marine trumpet and Arab ram's horn, at the Arab Tower, 40 miles west of Alexandria, he made short shrift of a threatened mutiny, Lt. O'Bannon reported, by seizing the two ringleaders and "decapitating each of them with a single stroke [of his scimitar], performing this grisly act with a tranquility of spirit astonishing in one who so frequently displayed a tenderness to all of his fellow human beings." The other Arabs, he added, "learned a salutary lesson" from "the dripping heads of the culprits mounted on pikes."

Throughout the six-week march, Eaton led his horde of riff-raff across some 700 miles of unfamiliar desert with navigation so sure even the Arabs considered it miraculous. The recollection of the dripping heads kept the troops in line, and there is no record of their plundering from the nomadic tribes they met. Eaton courteously requested permission to share water and grass at oases he found with uncanny instinct and blythely sold his rented camels to purchase food and supplies. A group of 120 Bedouin horsemen volunteered along the way, and, as they approached Derna, nomads with families and livestock fell in, despite Eaton's original determination that the corps would be exclusively military. Discipline slipped considerably, but the officers got their laundry done.

U.S. Navy vessels appeared on schedule with fresh supplies the day after Eaton's army reached the beaches east of Derna, furthering the commandant's reputation for miracles. The officer who came ashore was ' dismayed at the "general's metamorphosis, noting in his log, "I frequently felt I was not speaking to a State Department representative, but to one who was born in the desert of Barbary." The shock was mutual: Eaton learned that the Commodore had refused his request for an additional 100 Marines and had sent less money than promised; more important, he declined to guarantee terms of Eaton's agreement with Hamet.

After three days of rest and intelligence gathering, Eaton sent an offer of amity to the governor of Derna, who replied with a terse "My head or yours." Eaton deployed his troops, and the next morning the Navy opened fire, "Harriet's army" attacked from several quarters, and before evening Derna was secured. A counter-attack from the west by Yusef's forces was put to rout about two weeks later.

To Eaton's everlasting bitterness, he was never permitted to realize his grand scheme. Instead of marching on to Tripoli, he remained at Derna, military governor in all but name, while the Navy continued its blockade of Tripoli and the State Department negotiated for the release of more than 300 officers and men from the frigate Philadelphia, captured after their ship ran on a reef in the fall of 1803. Yusef's original ransom demand of $500,000 immediately and $500,000 annually in perpetuity was reduced to a bargain rate of $60,000, and the negotiator agreed to the face-saving token payment. Yusef was allowed to remain in power, however diminished, and poor Hamet took off once more into the desert with his small retinue.

Although Eaton's path to glory had effectively weakened the terror of the Barbary pirates, it took Stephen Decatur's return to the Mediterranean in 1815 to put an end to tribute to the Arabs for the time being.

Finally ordered from Derna, Eaton returned home, a popular hero and an embarrassment to the government. After much quibbling, he received a legitimate commission as Brigadier General, but no post, and reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses. In gratitude, Massachusetts awarded him 10,000 acres in Maine, half of which he later sold to pay off gambling debts. Bitterness and what he considered his betrayal by timid diplomats devoured him and - previously an abstemious man - he delighted his enemies and humiliated his friends by consorting publicly with low women, gambling away his fortune, and habitually making a public spectacle of himself. As a recent Smithsonian article on the Tripolitan wars put it, succinctly: "he got drunk, stayed drunk, and died six years later."

GEN. AND HAMET CARAMELLI With their forces passed the Desert of Barca,after much toil and suffering:theretook, possession of Derne the CapitaL of a Province of Tripoli in Africca in 1805

GENERAL EATON.

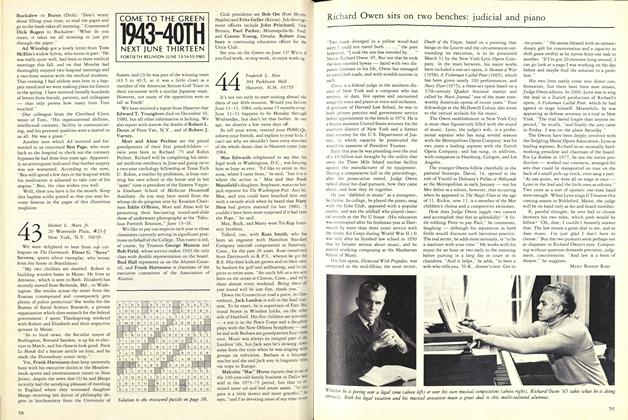

While Eaton plotted his land war, theNavy was bombarding Tripoli in anattempt to persuade the Bashaw to free theofficers and crew of the Philadelphia. This1804 engraving was dedicated to theAmerican commander.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

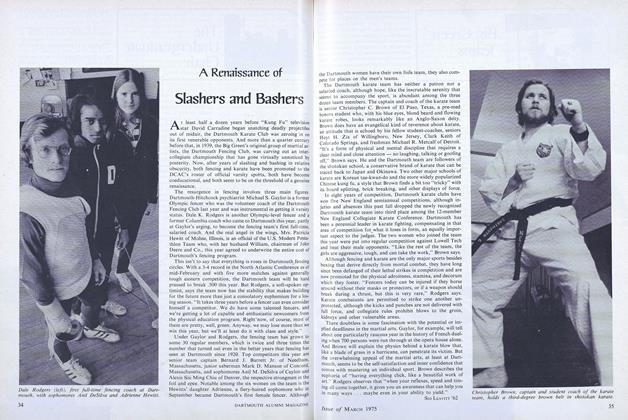

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

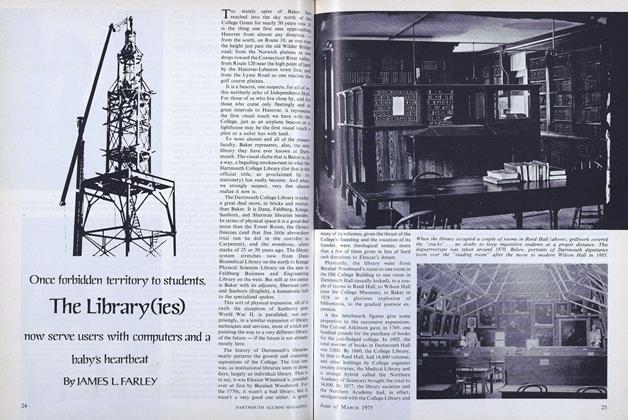

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleVox

March 1975 By HOWARD

MARY BISHOP ROSS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May/June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR KIDS OUTDOORS WITH HI-TECH GIZMOS

Jan/Feb 2009 By DERRICK CRANDALL '73 -

Feature

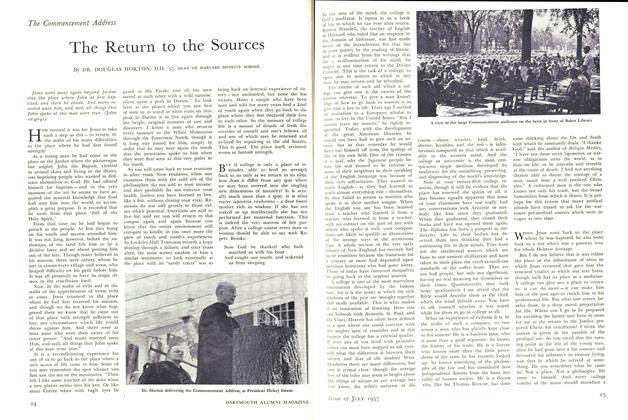

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Year 1968: A Reprise

DECEMBER 1968 By EDWARD W. GUDE '59, INSTRUCTOR IN GOVERNMENT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71