CAN there be a backward Dartmouth student? Consider me one. My family is from New Hampshire, close to Hanover, but most of my childhood was spent in Europe. It took three years at a New Hampshire prep school for me to learn enough English to be admitted to college.

So why, after one year on campus, leave everything I came "home" to and go back to Europe to study languages for 12 months?

Considering the direction of most Dartmouth foreign study programs, mine was backwards, but it proved (at least to me) that you can go home again, to both sides of the Atlantic.

My father was in foreign service, and I was born abroad and went to French schools in Switzerland and Germany until the age of 13. After a year in Thailand, we came back to the States, the prep school, and Dartmouth.

Dartmouth's German Department approved my plans for the Goethe Institut Language Study Program in Murnau for January and February, 1973. My spring term was spent at the University of Mainz on the Foreign Study Program. The summer I had to myself and fall term was in Foreign Study at the University of Toulouse. Unforeseen then was the opportunity of taking part in the Spanish Foreign Study at San Luis Potosi, Mexico.

MURNAU: After a morning of class at the Institut, I head for lunch at one of the five restaurants where my coupons are valid. Explain to the over-helpful waitress that I had the Knoedl Suppe and Sauerbraten yesterday and today it will be the Geflüglreis "Hawaii." The waitress smiles and leaves to fetch the order. This small event nearly prompts a tap dance on the table. Why? Simply because in class that morning we mastered the ways of ordering food; this is the first time I've been able to do it without pointing a finger and saying, "Das." As a matter of fact, there is even a foray into the past tense. Talk about simple pleasures!

Progress is rapid and daily I use words just learned in class. All classes are taught only in German because over 100 students of many nationalities are participating. I gain an advantage by associating only with non-English speaking students and forcing myself to speak either French or German. My Japanese roommate and I play gin "lummy," communicating in broken German. Along with 12 other students, we live as boarders in a large farmhouse. It is a good way to begin my European stay - and gives me an international evaluation of the German character.

Weekday afternoons are frequently taken up by chess, with my most memorable games played against a Turkish student (or, rather, all ten of them). The usual outcome: an all-out brawl among the Turks, the result of disagreements about how to beat "Der Amerikaner." A good friendship with a Swiss ski instructor leads to personal lessons at Garmisch and Mittenwald. Watching the World Cup Downhill in Garmisch provides a real thrill, supplemented the following weekend by the World Championship Ski Bob races.

Germans use their "Baden" for all sorts of cures, and we relax ski muscles in Kurorten, south of Munich. For 83 cents I rent a suit and a cap and swim for three hours in indoor and outdoor pools. Hilarity breaks out on class sightseeing trips to Augsburg and Munich, if only because of our inability to understand much of the tour guides' explanations. As the program ends, our distress at not seeing one another again is alleviated by Fasching, the local pre-Lenten festival. Adultery is not grounds for divorce during these few weeks, or so we are told, and I believe it. Amid this festive time the course ends, and I feel as if I'd just lived a whole life. These two months have been brim fulla total learning experience and more than I'd expected plus exactly what was needed after four terms at Dartmouth where I was rapidly becoming saturated with "book knowledge."

KITZBUEHEL: What could be wiser than to devote the month's interlude between the Institut and Mainz to skiing in the place I'd skied as a kid? Within two days I find a job as a Liftbedienstter in Kitzbuehel, helping riders off the highest chairlift in the area. What a view from that altitude! By a not-so-amazing coincidence one of those riders is classmate Mike Caldwell who'd asked in Hanover where the good snow was likely to be when he finished his studies in Berlin. We trade many stories.

At the end of that month of work and skiing, I welcome the warm invitation from an old friend to visit at his castle (and my birthplace) in Anif, a small town near Salzburg. I spend three royal days there, served by a maid and a butler (with white gloves) and treated to a chauffeured tour of Salzburg with the Count as personal guide. Count Moy then presents me with a first class rail ticket to Mainz, and I embark on yet another "life," that of a student at the University of Mainz.

MAINZ: I arrive at the Hauptbahnhof at 3 a.m. Still in the clouds from those unreal three days, I walk out of the station to see a man lying in the street, apparently dead, step around him as an ambulance arrives, wander into the city, and promptly get lost. Awakening next morning, warmly bundled in my sleeping bag, I wonder where I am. Oh, simply lying among various discarded items in a small dump which had, the night before, appeared to be a nice, grassy patch near the train tunnel.

Back at the station I meet classmate Dave Thompson who is going to live with me at the Diekelmanns, our host family. Duly picked up by the misses of the family, we begin to adapt quickly to our new situation. Herr Diekelmann invites us to join him in his favorite activity - walking, a very German custom. Tramping five miles through public forests, we hear about Mainz, a conservative town with little industry and a Catholic majority. It was destroyed two days before the end of World War 11. We spend three days filling out endless forms, all of which have to be stamped many, many times - another German custom (or European custom, or, increasingly, American).

As classes begin, I have to apply myself - I haven't ever read a German book and the literature course covers 300 years, from Kleist to Boehl. In all, an average of 100 pages of reading a week, plus grammar work. Once I invent the "one-hand dictionary technique," things go faster. Socially, I luck out. After only one week in Mainz, I meet a German girl in a Weinkeller and we are together during the rest of my stay (and have been in touch ever since). Susanne gives me an unparalleled chance to be "inside" of the German way of life, and my rapid progress toward a semblance of profiency in the spoken language is due mostly to her. As my host German family doesn't go out much, I join Suzanne and her family in taking in movies and jazz, rock, and classical concerts. School-related trips include visits to three or four vineyards where a short lecture on the hows and whys is followed by a session of tasting. It comes to the point where Dartmouth students are better judges of good wine than most Germans. "69 Moesel Qualitaetswcin? Ah, yes, a very good year."

The highlight of the Mainz program is Berlin. The five days of our visit seem to pass as fast as the 10-hour ride to get there. Museums, the zoo, a chartered tour of the city, many plays and concerts. The big activity of that week is the parade in East Berlin to celebrate those Communist commune workers who surpassed their annual production goal. It amply demonstrates that Communism isn't just a theory described in a political science book. I leave Berlin with the impression that it is glowingly alive but, with afterthought, I believe that the city is, in fact, dying, its inhabitants terrified of the Communists. There is a tenseness in the air. A man has just been shot trying to escape over the wall.

On June 1 classes end, and I leave Mainz to spend two months visiting old family friends in Paris, Geneva, Salzburg, Munich, Tubingen and other, smaller places. Hitching is serendipitous.

My favorite hitch comes on the way to two weeks at Schloss Anif. After a friend and I are deposited at Chiemsee to spend an afternoon viewing Crazy Ludwig's replica of Versailles, we wait for the Count to return from Munich. At the highway entrance are six other hikers. I'll never forget their faces as the Mercedes limousine pulls up and we are ushered into the car. The Count tips his hat to the group on the roadside, and we leave for "home." A hitchhiker's dream and even though it is prearranged, the glory of it never diminishes.

So, after two months of traveling, I spend the rest of the summer repairing a 250-year-old farmhouse in a small town near Freiburg for a man I'd met in Mainz. It is a time of leisure, peace, and reflection.

The summer ends quickly, however, and I start on the long trek to Toulouse. After a disastrous few days in Lyons where I lose my passport and travelers' checks, luck provides me with a free train ride straight to Toulouse, compliments of the French Communist Party - the trains are running but the ticket takers are on strike.

TOULOUSE: I draw an exceptional family. I am frequently taken out to eat and very well treated by them and their friends. As for classes, they are excellent. "Camus," taught by M. Fromilhague, is especially good. But we are taking five classes, which leaves little time for personal diversions. Except for my extravagant purchase of a Solex motorbike, I would feel very restricted since the buses stop running at 9 p.m.

Unfortunately, a strong case of homesickness taints much of my enjoyment of Toulouse. The constant compromise is depressing and produces an exaggeration of "how great it is back home." Musing on this, I can see that I am merely trying to regain my independence lost to the rigidly defined French role of "son and brother." But through Francoise, my "sister," and our interminable discussions, I pick up all the latest slang and phrases to the point that a Frenchman can't tell from my accent that I am in fact an American.

I return to the States a rather confused trilingual Dartmouth student. I've digested an awful lot of information in one year, and need time to classify it properly. It takes a while to readjust to the "American way."

After a winter at home in Cornish Flat cutting firewood, I spend two terms at Dartmouth and then am off again, this time to Mexico.

SAN LUIS POTOSI: Because I have no cultural attachment whatever with Mexico and because I can't possibly "blend in" as I had in Europe, much less is expected of me here insofar as living style and customs. I am treated mostly as a tourist, and being so very different affords an objectivity which was impossible in Europe. We are treated as Americanos - some love us, some do not love us, many ignore us. To generalize, everything seems either black or white. It is an easy way out in dealing with the people. My family treats me well, but there is no feeling either way. I have a better rapport with the maids who cook and clean for me.

But, of all the programs, this is the most fascinating; it is like jumping into NationalGeographic magazine. Along with a few other students, I "run the bulls" in San Miguel Allende. Dashing up a cobblestone street with eight bulls hot after me and slipping behind a gate at the last second is something I'll never forget. Neither will I forget eight vacation days spent in Puerto Vallarta on the West Coast, snorkling and relaxing.

What strikes me most about Mexico is the "macho" spirit, the supreme male chauvinism. Men are almost expected to cheat on their girlfriends and wives, who in turn must remain at home and wait unless they go out with a chaperone. Marriage is the number one female priority; the ones who don't achieve it either travel for extended periods or stay home to take care of ailing parents. Because of the shortage of men, the women are in great competition to find a husband, any husband. Although seemingly shy, girls at even a young age become very skilled in the art of getting a man. We are repeatedly warned of this by our professor. For a Mexican girl to "get" an American husband would be a crowning achievement. There is nowhere to escape to, as the nearest big city is five hours away - San Luis is in the middle of a desert. It seems as if most people know each other, and if we stay on much longer I think the plots within families bent on having an American son-in-law will thicken.

HOME: The most positive aspect of my four terms away from Dartmouth was the sense I had of "living" while learning. Even if prospective employers don't seem very impressed with a French major, I gained something relatively concrete out of my liberal arts education. If "variety is the spice of life," the variety I experienced as a Dartmouth student on the road couldn't have been more enchanting.

Hitchhiker's pad.

Robert Hier '75 poses in farmer Hans'doorway near Freiburg, summer of '73.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

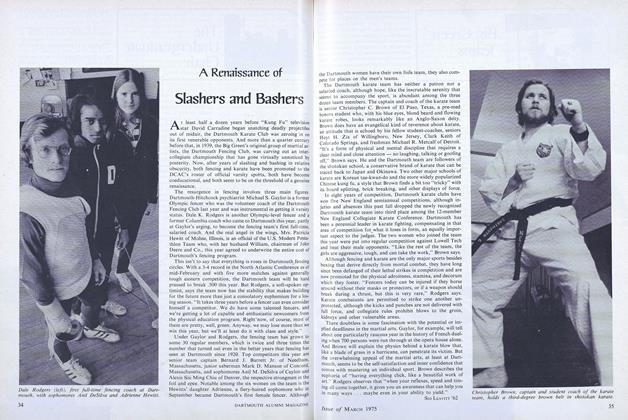

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleVox

March 1975 By HOWARD

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

FEBRUARY 1968 -

FEATURE

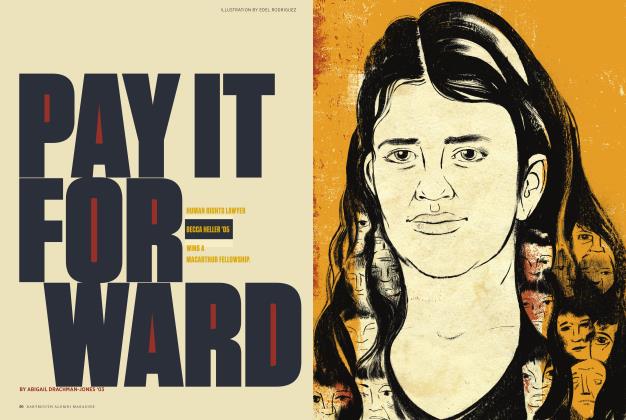

FEATUREPay It Forward

MARCH|APRIL 2019 By ABIGAIL DRACHMAN-JONES '03 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May/June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureGolden Memories

May/June 2012 By SARAH SCHEWE ’12 -

FEATURE

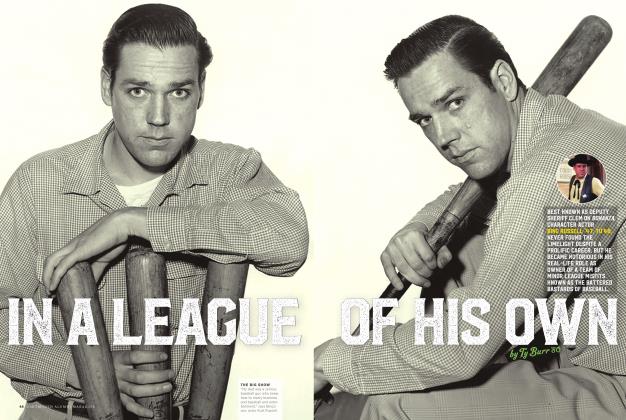

FEATUREIn a League of His Own

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By TY BURR ’80