now serve users with computers and ababy's heartbeat

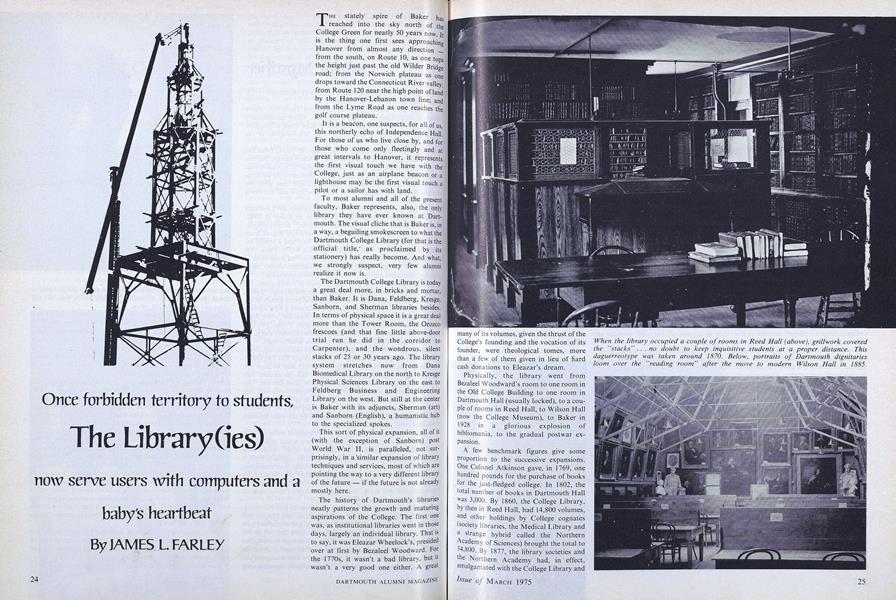

THE stately spire of Baker has reached into the sky north of the College Green for nearly 50 years now. it is the thing one first sees approaching Hanover from almost any direction - from the south, on Route 10, as one tops the height just past the old Wilder Bridge road; from the Norwich plateau as one drops toward the Connecticut River valley; from Route 120 near the high point of land by the Hanover-Lebanon town line; and from the Lyme Road as one reaches the golf course plateau.

It is a beacon, one suspects, for all of us this northerly echo of Independence Hall! For those of us who live close by, and for those who come only fleetingly and at great intervals to Hanover, it represents the first visual touch we have with the College, just as an airplane beacon or a lighthouse may be the first visual touch a pilot or a sailor has with land.

To most alumni and all of the present faculty, Baker represents, also, the only library they have ever known at Dartmouth. The visual cliche that is Baker is, in a way, a beguiling smokescreen to what the Dartmouth College Library (for that is the official title," as proclaimed by its stationery) has really become. And what, we strongly suspect, very few alumni realize it now is.

The Dartmouth College Library is today a great deal more, in bricks and mortar, than Baker. It is Dana, Feldberg, Kresge, Sanborn, and Sherman libraries besides. In terms of physical space it is a great deal more than the Tower Room, the Orozco frescoes (and that fine little above-door trial run he did in the corridor to Carpenter), and the wondrous, silent stacks of 25 or 30 years ago. The library system stretches now from Dana Biomedical Library on the north to Kresge Physical Sciences Library on the east to Feldberg Business and Engineering Library on the west. But still at the center is Baker with its adjuncts, Sherman (art) and Sanborn (English), a humanistic hub to the specialized spokes.

This sort of physical expansion, all of it (with the exception of Sanborn) post World War II, is paralleled, not surprisingly, in a 'similar expansion of library techniques and services, most of which are pointing the way to a very different library of the future - if the future is not already mostly here.

The history of Dartmouth's libraries neatly patterns the growth and maturing aspirations of the College. The first one was, as institutional libraries went in those days, largely an individual library. That is to say, it was Eleazar Wheelock's, presided over at first by Bezaleel Woodward. For the 17705, it wasn't a bad library, but it wasn't a very good one either. A great many of its volumes, given the thrust of the College's founding and the vocation of its founder, were theological tomes, more than a few of them given in lieu of Hard cash donations to Eleazar's dream.

Physically, the library went from Bezaleel Woodward's room to one room in the Old College Building to one room in Dartmouth.Hall (usually locked), to a couple of rooms in Reed Hall, to Wilson Hall (now the College Museum), to Baker in 1928 in a glorious explosion of bibliomania, to the gradual postwar expansion.

A few benchmark figures give some proportion to the successive expansions. One Colonel Atkinson gave, in 1769, one hundred pounds for the purchase of books for the just-fledged college. In 1802, the total number of books in Dartmouth Hall was 3,000. By 1860, the College Library, by then in Reed Hall, had 14,800 volumes, and other holdings by College cognates (society libraries, the Medical Library and a strange hybrid called the Northern Academy of Sciences) brought the total to 34,800. By 1877, the library societies and the Northern Academy had, in effect, amalgamated with the College Library and the volume total now reached 54,600.

With the dedication of Wilson Hall in 1885, the first building expressly designed as a library at Dartmouth, library-keeping took a quantum jump. The building was designed for a 130,000-volume collection and it was "absolutely fireproof."

Baker, of course, was the next quantum jump, one more or less demanded by the College's large enrollment increase in the 19205. Although as a building it represented the remarkable fruits of President Hopkins' development roulette with George F. Baker, it was for a couple of decades nothing more than a larger, more elegant, and superbly supplied version of Wilson. Before too long, however, Baker became a great deal more imposing than its predecessor in the number and variety of its collections - 300,000 volumes in a few short years to grow steadily to the roughly 1,200,000 today.

Over the years there have been some rather odd notions about library use, and an occasional odd user, a type that libraries wherever they are situated seem to attract. For instance, in the late 18th century, the library room was open the liberal amount of one hour every two weeks for each class. Further, no more than five students were allowed in the room at a time (open stacks indeed!), and book withdrawals were permitted on a graduated scale - freshmen, one at a time; sophomores and juniors, two; grand old seniors, three.

Then there was one Ephraim Smedley, Class of 1793, the 18th century archetype of today's "weenie." He not only booked mightily, he kept track thereof. He totted up his sophomore year's booking at 7,913 pages, or roughly 44 a day for the 180-day school year. He had a neat apothegm to offer in connection with his feat: "A very small number of pages to read but a few well attended are better than a large number slightly run over." Neat or not, he died at the end of that year, perhaps all read out.

Nathan Lord, the College's sixth president, had some remarkable ideas about library use. They clearly reflected a notion held in the first half of the 19th century that the library was primarily for the convenience of the faculty. In his 1859 report to the Trustees, President Lord said: "The Library has been closed to students all the spring term, except that any have been permitted to draw books on the special order of any teacher. No inconvenience whatever has resulted, in the judgment of the librarian. . . . From anything that now appears the Library might remain closed with equal advantage a much longer period of time."

This is indeed a far cry from the 19705, when portions of the library have been left open all night for student study enclaves and the decades of open stack availability is only beginning to be hedged about slightly. But then, it is all a far cry from Reed and Wilson and even the pre-war Baker, this Dartmouth College Library system of today.

If one can pick upon a single word that would best typify the difference it would be "automation," that word that makes most humanists shudder. Shudder or not, one must move with the world and the form of automation that has invaded library science is not the robot-like, unthinking, and uncorrectable automation that so often infuriates one with its recorded messages and zombie airs. Rather, it is automation of the most helpful and imaginative sort.

The good Dr. Johnson, who had a thought about everything and words to spare to utter it, once observed, "A man will turn over half a library to make one book." That was undoubtedly true in the good doctor's coffee-house days, but a modern-day writer would need make no such hectic, book-flipping, journal-leafing search.

Now, a computerized marvel called "data base" is at the writer's beck and call. Let us conjure a young historian named Tweed Truman, who is working on a piece on the Bull Moose movement and its effect upon traditional Republican attitudes in the early 20th century. Young Tweed has read, of course, the standard works on the Bull Moose Party and American politics - F. E. Haynes, B. P. DeWitt, Harold R. Bruce - and he has dipped into biographies of Robert M. LaFollette Sr., Albert Beveridge and, of course, Teddy himself. But our Tweed is a digger, a devoted researcher and, among other things, he wants to know how the Bull Moose party fared in New Hampshire in 1912.

With the aid of an experienced and friendly Dartmouth College bibliographic searcher, Tweed can go to a computer console and, in a matter of a few minutes, by feeding judicious questions into the machine, extract a complete bibliography of journal references to the Bull Moose campaign in New Hampshire. The computer would spit out not only the references to articles, but brief abstracts of them.

As a result, Tweed might get, say, a reference to an article in The Progressive by Norman Hapgood about Governor Robert P. Bass of New Hampshire, a leader in the party bolt, and another about an interview in the Boston EveningTranscipt with the American novelist, Winston Churchill, who also was a leader in the movement in New Hampshire. Thus he has gotten (and in handy printed form, too) valuable references that would have otherwise taken him untold man-hours of poring through indexes and abstracts of journal literature.

And that reference to the Boston Evening Transcript article will lead him to yet another of the library's automated aids - its splendid array of microforms, now housed in the equally splendid Jones Microtext Center, just opened this year in well-equipped quarters off the Reserve Corridor. There Tweed can ask for, and get, the proper roll of microfilm for the Evening Transcript for early June, 1912, and soon have projected for him the interview with America's Winston.

Microform is one of the fastest growing mechanical aids in use in the libraries of today. Although the photographic process that produces microforms has been known for more than 100 years, it really never came into widespread use until the phenomenon known as V-Mail occurred during World War II. This process of reducing letters to little bits of film, hurrying those bits in vast quantitites over the oceans, and then reproducing them again in letter size not only helped boost millions of servicemen's morale, but it also demonstrated the practicality of the method.

The very name, microform, is anathema to most bookmen, those lovers of fine bindings and rare imprints. To them, a library should be only what its Latin derivative, liber, suggests - a repository of books in book form. Anathema or not, microform is here to stay in the modern library and, bookmen aside, a very good thing it is, too. In general terms, microform allows libraries to do two things they would not be able to do without it. First, they can store lots of bulky materials in convenient, handy, and replaceable forms; and second, they can have access to copies of rare (ah there, bookmen!) and in no other way duplicated volumes.

The storage aid is no mean plus factor in this day of mountains of materials spinning off the printing presses of the world. Anyone who has used bound volumes of newspapers, those out-size, dusty, sneezeinducing tomes, in a research project can appreciate the handiness and ease of microfilmed copies of papers. Or anyone who has handled a bound volume of newspapers of 50, 60, or 100 years ago knows the heartbreaking brittleness of old newsprint and has come, with a pang, upon whole pages torn out of the binding.

Microform is not restricted to rolls of film containing whole files of newspapers or magazines. There is a branch of it called microfiche in which book pages are reduced to incredibly small size and gathered together on cards. These, in turn, can be blown up to easily readable size. Microfiche and its companion ultra microfiche, a still more minute reduction, are eminently suitable for copying the codices of Leonardo, for instance, or other extremely rare books, making them available to many libraries for scholarly use.

The library's holdings of microforms is now of impressive size, something over 400,000 items, all of them acquired since World War 11. When one considers that a large (and expensive) physical addition was made to Baker's stacks in 1959 to house the mounting numbers of books, and when one wonders how another such addition could be made, short of dwarfing the stately spire, the importance of microforms merely in library housekeeping, to say nothing of rare acquisitions, is readily apparent.

There are other aids that modern electronics and communication have added to the librarian's kit of tools. Some of them are, at first blush, only internal aids, ones that help keep the library in order with far less sweat of brow. There is, for instance, push-button cataloging. Rather than the once laborious writing out of catalog cards by hand (or the later only slightly less laborious method of typing them out), the cards for the Dartmouth College Library system are now produced automatically in far-off Ohio. This is an aid, quite naturally, to catalogers, but it is also a boon, albeit not quite so apparent, to library subscribers. Because of the rapid and automatic production of the catalog cards, books acquired by the Dartmouth College Library reach the shelves sooner and their alter egos, the cards, are cataloged quicker, and thus the subscriber has. books made available to him sooner.

There are other aids, too, which were not available 50 years ago. Let us suppose, for example, that young Tweed has discovered that there is a book about John Peter Altgeld, the reforming governor of Illinois, that has a seminal bearing upon some of the later Bull Moose philosophy. There is one trouble about this, though. It is a book that Dartmouth does not have.

However, it is thought that a likely library to possess this book is the Chicago Public Library. In the old days (and not so very old at that) determining whether the Chicago Public Library indeed did have the book on Altgeld would have entailed writing a letter of inquiry and the subsequent delay until the answer arrived by return post. Today, a Dartmouth librarian needs merely to go to the teletype (TWX) keyboard and query his counterpart in Chicago directly. The answer will be obtained almost instantly and, if the book is available, it can be ordered on a library loan right away. The Dartmouth College Library is connected in this manner with all other libraries which have TWX systems. The library can, and has, ordered books on loan via TWX from European as well as American libraries.

There are other evidences of automation in the library system - the copying machines, coin-operated, which are available for subscribers' use in the various units of the system, Baker, Feldberg, Kresge, Dana. Students, writers, researchers need take far fewer notes than they once did.

Too, there are the tours of the library, whereby one can get to know the art in Baker (the Orozco frescoes, the portraits, the antique furniture) and see the original library furnishings of Bezaleel Woodward and become acquainted with the various areas of subscriber service. These tours are not led by a human guide. Instead, the tourer gets a tape player and follows along from station to station within Baker listening to the recorded facts and figures. A similar tape recording is available in the Reserve Corridor to explain the history and significance of the Orozco frescoes.

There are other, more specialized library automated aids. For instance, the Dana Biomedical Library has mannequins to help teach the medical student his profession - eye diseases can be simulated by slides inserted in a mannequin head. It also has video-tape instructional material and it has recordings of infant cries and heart sounds.

All of this may come on a bit strange for those of us who once read (and slept) in cushioned ease in the Tower Room, or who wandered, unguided (electronically or otherwise) in continued awe past Orozco's oranges and reds and whites, or who spent untold hours of pleasure in a library world once circumscribed by Baker, Sanborn, and Carpenter. That sort of library world somehow or other conjured up dreams of slippered ease, a gently hissing fire and a meerschaum pipe. The real - or today's - library world may be different, but it is no less pleasurable than that dreamy, and inaccurate, world of yesterday. The pleasure comes from the vastly increased board 'of literary morsels spread before one, a feast of knowledge with illimitable courses. And one that is served with accuracy and efficiency that, under the old methods, would have been too costly to have dreamed of.

Sir William Osier once wrote, "Money invested in a library gives much better returns than mining stock." Indeed it does, but it does so today only by using all the tools of modern communication. Plutarch's dictum, if read with an eye to computers, microforms and the rest, has a special meaning for us today: "Lucullus' furnishing a library, however, deserves praise and record, for he collected very many choice manuscripts; and the use they were put to was even more magnificent than the purchase."

When the library occupied a couple of rooms in Reed Hall (aboveJ, grillwork coveredthe "stacks" . . . no doubt to keep inquisitive students at a proper distance. Thisdaguerreotype was taken around 1870. Below, portraits of Dartmouth dignitariesloom over the "reading room" after the move to modern Wilson Hall in 1885.

A preliminary design by College architect Jens Frederick Larson shows an opengallery stretching across the front of Baker. Happily, it disappeared from the finalplans. At right, Larson's drawing of a presentation key for donor George F. Baker.

An artful photograph of the Baker stacksduring the time of construction in 1927.

In 1933 Jose Clemente Orozco confrontedthe legendary Quetzalcoatl (or vice versa).

Mickey Mouse came to Baker in 1966, the work of daring student pranksters. NathanLord, protector of library sanctity 100 years earlier, wouldn't have been amused.

Completed in 1973, the Feldberg library forTuck and Thayer schools shows the shapeof things to come. (Compare with Wilson.)

The future is here: against a backdrop ofBaker's Georgian woodwork, a student peerscalmly into the screen of a computer reader.

Below, the title page of the library's onemillionth volume. Above, Anne Bradstreet's entire poem on ultramicrofiche.

James L. Farley has had a love affair withthe library since he was a freshman in1938.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

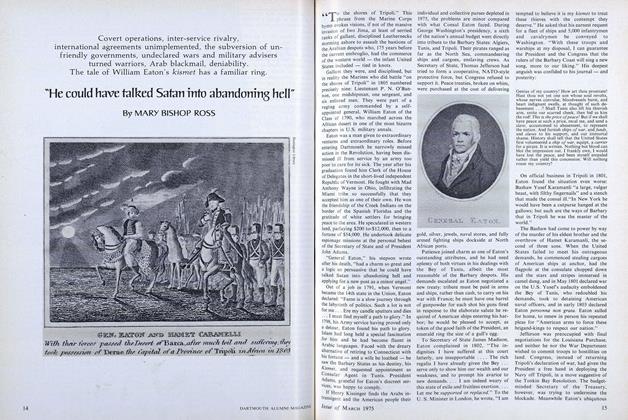

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

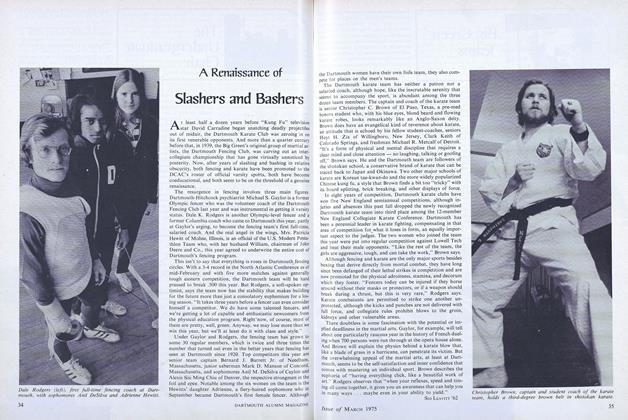

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleVox

March 1975 By HOWARD

JAMES L. FARLEY

-

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

January 1952 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1952 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

June 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

December 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

June 1951 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II

Article

-

Article

ArticlePres. Hopkins Leads Support for World Organization

October 1944 -

Article

ArticleDISTINGUISHED NASHUAN

JUNE 1963 -

Article

ArticleFill the Bowl up

November 1976 -

Article

ArticleThese three '43 pals

OCTOBER 1988 -

Article

Article"WHAT EVERY PROFESSOR OF SIXTY SHOULD KNOW"

January, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

January 1956 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29