FIVE men retire from the Dartmouth faculty this month, one only technically since he will continue to teach under a special research grant. Their tenure at the College ranges from five years to 41; together they have accumulated 124 years of service.

This year, rather than sketching their undeniable credentials and distinctions, we thought it fitting to allow these about-to-be emeriti to speak for themselves, to muse as they chose about teaching, about Dartmouth, about how they see themselves as people and as preceptors.

Artist, communicator, microbiologist, philosopher, and physicist: individually and collectively, they seem to manifest quite splendidly the "conscience, commitment, and comprehensivensss" which John Sloan Dickey defined as the aim of liberal learning.

Communication Between People

Dartmouth had severe financial problems when I came in 1934 and faces a money crisis as I leave in 1975. The difference: no one today so far has had to take a cut in salary.

My first year as a young instructor was frightening. But my students were exceptionally cooperative in helping the confessed stripling along; my colleagues stood by me when I failed a senior who later became an outstanding alumnus; my varsity debaters voted unanimously to give their entire $50 budget to the freshman squad. I knew I had come to the right place.

The early years included white-tie-and-tails houseparties, some provincialism among students who had never been west of the Hudson River or south of the Potomac. We continually lost to Yale in football - "the jinx" - but not in debate.

Dartmouth in the late '30s and early '40s had few apathetic students. True, they didn't storm Parkhurst, but intellectual clashes were vigorous and continuous. The major topics were socialism vs. capitalism, isolation vs. internationalism. Public debates packed the old Dartmouth Hall, and an Armistice Day discussion in Webster caused the postponement of classes. Many students volunteered for the Canadian armed forces before Pearl Harbor.

Who can forget the frenzied wartime plans to make mathematics and physics instructors out of humanists and social scientists? If the Navy V-12 program hadn't appeared, Professor Maurice Picard and I, an ill-suited pair, would probably be struggling still with the pendulum. Thank God I was recalled to teach speech.

My impressions after the war are clouded by service as chairman of the Town Democratic Committee when Truman was the candidate in 1948. No money, no support, and a coup de grace by a loyal Democrat who apologized for his Dewey vote.

Students of the 'sos and '6os were more sophisticated, often putting me on the spot with questions which guaranteed I would be a better teacher the next term. At that time I began my course in "Legal Argument" which has been a joy for 25 years.

Students then seemed more interested in learning than in grades. Lately I have become a bit depressed as the student body, more cosmopolitan in one sense - more "with it" - seems forced to place grades ahead of knowledge for knowledge's sake.

Do I have any last words? 1) Co-education has been a great step foreward. 2) I would like to see a revival of genuine student government, one way to train leaders. 3) I hope the three divisions of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences will be eliminated. 4) I trust some day soon a School of Communication will be established at Dartmouth. Communication between people with varying languages, cultures, problems, and goals is essential to the long-range unification of our shrinking planet into a harmonious and happy world.

JOHN V. NEALE Professor of Speech

To Raise the Tide of Life

I like to associate Dartmouth with Robert Frost and I like his line that he was "never agreed that he'd be any institution's need." This is not to say that I am lukewarm about Dartmouth. On the contrary, I have become very fond of it. The 14 years that I have spent here have been enjoyable. In addition to association with pleasant people, I have been ideally located for carrying on virus research at the Medical School. Virology is my profession, but I've always been leary of pouring one's whole life into one narrow specialty. A way out, in my case, has been to teach subjects in the humanities as well as in science. Dartmouth has given opportunities to do this: an elective on Medical History conducted in my library in Lyme; another, teaching freshman seminars in the College. I like discussion, interchanges of ideas with students. The central concern of the humanities should be to raise the tide of life.

All this comes back to not being, as Frost said, any institution's need. One should live with a margin of leisure. Education is life-long, and it should be self-education, education to live well and better. This idea first came to me when I read Emerson, Thoreau, and Benjamin Franklin's autobiography at 14 years of age. These men have remained an inspiration ever since. Possibly this is why I regard retirement as a purely institutional affair, nothing to do with life itself. I have yet, to use a term of Frost again, much "unfinished business," for I have been, as long as I can remember, much interested in ornithology and natural history. I never wanted to spoil my interest in these subjects by being a professional. They go well with other things.

If I should have another chance to conduct a freshman seminar (and I hope I will for I have research grants that will keep me at Dartmouth for at least another three years), I would continue to harp on the ideas I love. I would urge freshman to take their education into their own hands. It is something too important to entrust to others. Develop the things you love to do, be yourself, and be open to the beauty of nature. The goal of life should be happiness, a notion familiar to whole men from Aristotle to Emerson and Thoreau, but rather lost sight of today.

LAWRENCE KILHAM, M.D. Professor of Microbiology Dartmouth Medical School

More and More,Less and Less

"Now that Dartmouth has committed itself to you," said the dean on my appointment, "what about you committing yourself to Dartmouth?" "Permanently?" I enquired. "Permanently," he replied. "Well, what do you suggest I do?" Said he: "Buy a lot in the cemetery." (Whether wisely or not, I delayed that for a few years.)

He was more encouraging about life-styles. "You have a choice; you can be a character or a committee-man." The answer to that was simple; I had no choice. In some sense I was already a character and could never have become a committeeman. Indeed for 17 blessed years I was never elected or appointed to a committee - though then I had to serve, on the ground that they needed some character who had been around long enough to know what this or that regulation had meant (if and when it had meant anything).

The New Dartmouth of Today and Tomorrow is not so different from the Dartmouth I came to. More mobility; more open informality; perhaps less granite in the brains. Less departmentalism; though somehow the faculty seem to know less and less about more and more, while the students know more and more about less and less. Co-education, the arrival and survival of professoresses and studentesses has not made much difference. Dartmouth lads were always bringing their lasses to class. Now of course it is a little more difficult to tell a he from a she; many of them appear to be neither one nor tother (ne-uter, as we used to say in Latin); the only real problem (not confined to Dartmouth, not even to the U.S.A.) is how to prevent everybody becoming neuter.

T. S. K. SCOTT-CRAIG Professor of Philosophy

Bread for the Soul

I am grateful to all my former students, who shared with me the joy of seeing. Nothing ever pleased me more than to hear a student, after struggling with a visual problem, finally exclaim: "Oh, I see!"

I am deeply convinced that Dartmouth's Visual Studies Department fulfills a very important function by teaching students to think in visual situations. Many of the students who enroll in our courses do not intend to become artists; we have many aspiring scientists, lawyers, and doctors. To teach these students to see and appreciate art is especially important, since they are the future audience for the creative arts. In a world that is becoming daily more mechanized and dehumanized, art will provide them with what the painter Wasily Kandinsky, my great teacher at the Bauhaus, called "bread for the soul."

HANNES BECKMANN PROFESSOR OF ART

Young Minds Liberated

Undergraduate education has been and should continue to be the primary purpose of Dartmouth College. To fulfill that purpose students should be exposed to the excitement of scientific investigation and discovery through observing and occasionally assisting professors in their research. Young minds thereby may be liberated from relying solely on books. A laboratory can be as valuable as a library for the acquisition of knowledge.

When I arrived on the Dartmouth campus in May 1942 for the upcoming summer term (not an innovation even then), I found no secretaries, no technicians, only two or three graduate students, a few majors, and very little fundamental research underway in the Department of Physics. Astronomy was associated with mathematics. By 1944 World War II had transformed Dartmouth - officer training, V-12, 1,600 Physics 1 and 2 students in Silsby and Wilder Halls, numerous laboratory sections with professors from other departments as assistants, one secretary, one technician - no time for research.

Soon after World War II a handful of research-minded young professors in medicine and the sciences began meeting weekly for informal discussions over lunch. Here developed my interests in tissue elasticity and capillary flow. Members of the group have become dispersed or died. Only Professor Roy Forster, who retires next year, and I are left. During our tenures conditions changed slowly at first and then ever more rapidly until today undergraduate research is an accepted norm and undergraduate education has become immeasurably improved by it.

ALLEN L. KING Professor of Physics

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

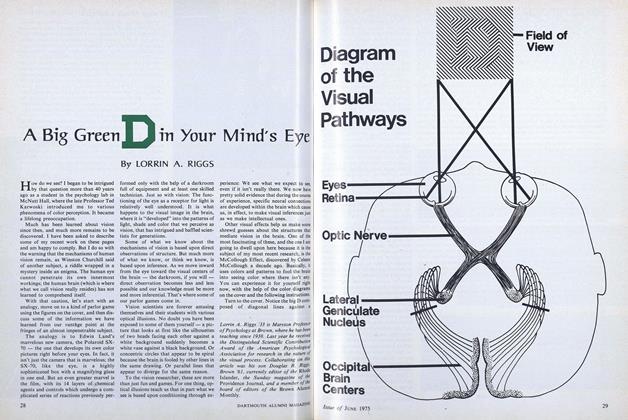

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975