I kept cool until I tried to take the hook out of his mouth. He was lying covered with sand on the little bar where I had landed him. His gills opened with his penultimate sighs. Then suddenly he stood up on his head in the sand and hit me with his tail and the sand flew. Slowly at first my hands began to shake, and, although I thought they made a miserable sight, I couldn't stop them. Finally, I managed to open the large blade to my knife which several times slid off his skull before it went through his brain.

Even when I bent him he was way too long for my basket, so his tail stuck out.

There were black spots on him that looked like crustaceans. He seemed oceanic, including barnacles. When I passed my brother at the next hole, I saw him study the tail and slowly remove his hat, and not out of respect to my prowess as a fisherman.

I had a fish, so I sat down to watch a fisherman.

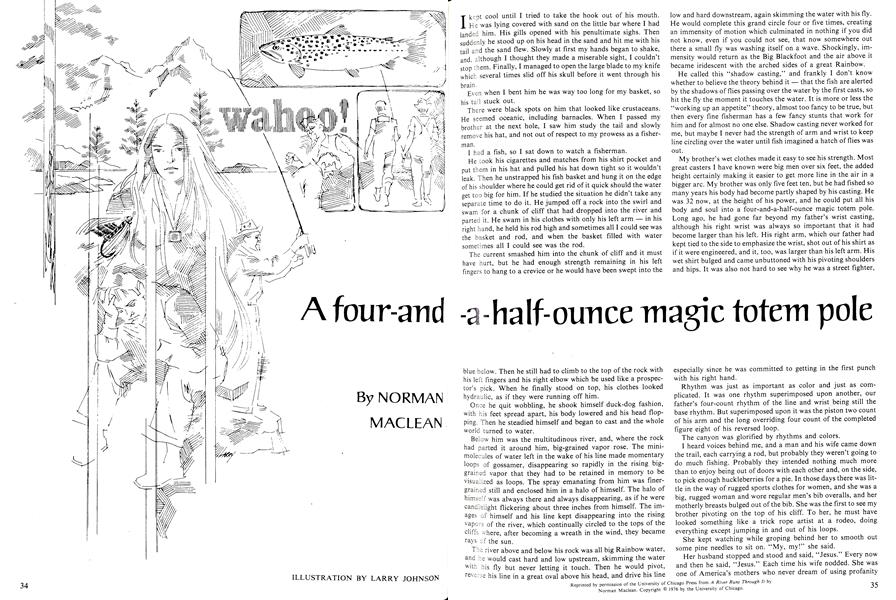

He took his cigarettes and matches from his shirt pocket and put them in his hat and pulled his hat down tight so it wouldn't leak. Then he unstrapped his fish basket and hung it on the edge of his shoulder where he could get rid of it quick should the water get too big for him. If he studied the situation he didn't take any separate time to do it. He jumped off a rock into the swirl and swam for a chunk of cliff that had dropped into the river and parted it. He swam in his clothes with only his left arm - in his right hand, he held his rod high and sometimes all I could see was the basket and rod, and when the basket filled with water sometimes all I could see was the rod.

The current smashed him into the chunk of cliff and it must have hurt, but he had enough strength remaining in his left fingers to hang to a crevice or he would have been swept into the blue below. Then he still had to climb to the top of the rock with his left fingers and his right elbow which he used like a prospector's pick. When he finally stood on top, his clothes looked hydraulic, as if they were running off him.

Once he quit wobbling, he shook himself duck-dog fashion, with his feet spread apart, his body lowered and his head flopping. Then he steadied himself and began to cast and the whole world turned to water.

Below him was the multitudinous river, and, where the rock had parted it around him, big-grained vapor rose. The minimolecules of water left in the wake of his line made momentary loops of gossamer, disappearing so rapidly in the rising big-grained vapor that they had to be retained in memory to be visualized as loops. The spray emanating from him was finergrained still and enclosed him in a halo of himself. The halo of himself was always there and always disappearing, as if he were candlelight flickering about three inches from himself. The images of himself and his line kept disappearing into the rising vapors of the river, which continually circled to the tops of the cliffs where, after becoming a wreath in the wind, they became rays of the sun.

The river above and below his rock was all big Rainbow water, and he would cast hard and low upstream, skimming the water with his fly but never letting it touch. Then he would pivot, reverse his line in a great oval above his head, and drive his line low and hard downstream, again skimming the water with his fly. He would complete this grand circle four or five times, creating an immensity of motion which culminated in nothing if you did not know, even if you could not see, that now somewhere out there a small fly was washing itself on a wave. Shockingly, immensity would return as the Big Blackfoot and the air above it became iridescent with the arched sides of a great Rainbow.

He called this "shadow casting," and frankly I don't know whether to believe the theory behind it - that the fish are alerted by the shadows of flies passing over the water by the first casts, so hit the fly the moment it touches the water. It is more or less the "working up an appetite" theory, almost too fancy to be true, but then every fine fisherman has a few fancy stunts that work for him and for almost no one else. Shadow casting never worked for me, but maybe I never had the strength of arm and wrist to keep line circling over the water until fish imagined a hatch of flies was out.

My brother's wet clothes made it easy to see his strength. Most great casters I have known were big men over six feet, the added height certainly making it easier to get more line in the air in a bigger arc. My brother was only five feet ten, but he had fished so many years his body had become partly shaped by his casting. He was 32 now, at the height of his power, and he could put all his body and soul into a four-and-a-half-ounce magic totem pole. Long ago, he had gone far beyond my father's wrist casting, although his right wrist was always so important that it had become larger than his left. His right arm, which our father had kept tied to the side to emphasize the wrist, shot out of his shirt as if it were engineered, and it, too, was larger than his left arm. His wet shirt bulged and came unbuttoned with his pivoting shoulders and hips. It was also not hard to see why he was a street fighter, especially since he was committed to getting in the first punch with his right hand.

Rhythm was just as important as color and just as complicated. It was one rhythm superimposed upon another, our father's four-count rhythm of the line and wrist being still the base rhythm. But superimposed upon it was the piston two count of his arm and the long overriding four count of the completed figure eight of his reversed loop.

The canyon was glorified by rhythms and colors. I heard voices behind me, and a man and his wife came down the trail, each carrying a rod, but probably they weren't going to do much fishing. Probably they intended nothing much more than to enjoy being out of doors with each other and, on the side, to pick enough huckleberries for a pie. In those days there was little in the way of rugged sports clothes for women, and she was a big, rugged woman and wore regular men's bib overalls, and her motherly breasts bulged out of the bib. She was the first to see my brother pivoting on the top of his cliff. To her, he must have looked something like a trick rope artist at a rodeo, doing everything except jumping in and out of his loops.

She kept watching while groping behind her to smooth out some pine needles to sit on. "My, my!" she said.

Her husband stopped and stood and said, "Jesus." Every now and then he said, "Jesus." Each time his wife nodded. She was one of America's mothers who never dream of using profanity themselves but enjoy their husbands', and later come to need it, like cigar smoke.

I started to make for the next hole. "Oh, no," she said, "you're going to wait, aren't you, until he comes to shore so you can see his big fish?"

"No," I answered, "I'd rather remember the molecules."

She obviously thought I was crazy, so I added, "I'll see his fish later." And to make any sense for her I had to add, "He's my brother."

As I kept going, the middle of my back told me that I was being viewed from the rear both as quite a guy, because I was his brother, and also as a little bit nutty, because I was molecular.

SINCE our fish were big enough to deserve a few drinks and quite a bit of talk afterwards, we were late in getting back to Helena. On the way, Paul asked, "Why not stay overnight with me and go down to Wolf Creek in the morning?" He added that he himself had "to be out for the evening," but would be back soon after midnight. I learned later it must have been around two o'clock in the morning when I heard the thing that was ringing, and I ascended through river mists and molecules until I awoke catching the telephone. The telephone had a voice in it, which asked, "Are you Paul's brother?" I asked, "What's wrong?" The voice said, "I want you to see him." Thinking we had poor connections, I banged the phone. "Who are you? I asked. He said, "I am the desk sergeant who wants you to see your brother."

The checkbook was still in my hand when I reached the jail. The desk sergeant frowned and said, "No, you don't have to post bond for him. He covers the police beat and has friends here. All you have to do is look at him and take him home."

Then he added, "But he'll have to come back. A guy is going to sue him. Maybe two guys are."

Not wanting to see him without a notion of what I might see, I kept repeating, "What's wrong?" When the desk sergeant thought it was time, he told me, "He hit a guy and the guy is missing a couple of teeth and is all cut up." I asked, "What's the second guy suing him for?" "For breaking dishes. Also a table," the sergeant said. "The second guy owns the restaurant. The guy who got hit lit on one of the tables."

By now I was ready to see my brother, but it was becoming clear that the sergeant had called me to the station to have a talk. He said, "We're picking him up too much lately. He's drinking too much." I had already heard more than I wanted. Maybe one of our ultimate troubles was that I never wanted to hear too much about my brother.

The sergeant finished what he had to say by finally telling me what he really wanted to say, "Besides he's behind in the big stud poker game at Hot Springs. It's not healthy to be behind in the big game at Hot Springs.

You and your brother think you're tough because you're street fighters. At Hot Springs they don't play any child games like fist fighting. At Hot Springs it's the big stud poker game and all that goes with it."

I was confused from trying to rise suddenly from molecules of sleep to an understanding of what I did not want to understand. I said, "Let's begin again. Why is he here and is he hurt?"

The sergeant said, "He's not hurt, just sick. He drinks too much. At Hot Springs, they don't drink too much." I said to the sergeant, "Let's go on. Why is he here?"

According to the sergeant's report to me, Paul and his girl had gone into Weiss's restaurant for a midnight sandwich — a popular place at midnight since it had booths in the rear where you and your girl could sit and draw the curtains. "The girl," the sergeant said, "was that half-breed Indian girl he goes with. You know the one," he added, as if to implicate me.

Paul and his girl were evidently looking for an empty booth when a guy in a booth they had passed stuck his head out of the curtain and yelled, "Wahoo." Paul hit the head, separating the head from two teeth and knocking the body back on the table which overturned, cutting the guy and his girl with broken dishes The sergeant said, "The guy said to me, 'Jesus, all I meant is that it's funny to go out with an Indian. It was just a joke.' "

I said to the sergeant, "It's not very funny," and the sergeant said, "No, not very funny, but it's going to cost your brother a lot of money and time to get out of it. What really isn't funny is that he's behind in the game at Hot Springs. Can't you help him straighten out?"

"I don't know what to do," I confessed to the sergeant.

"I know what you mean," the sergeant confessed to me. Desk sergeants at this time were still Irish. "I have a young brother," he said, "who is a wonderful kid, but he's always in trouble. He's what we call 'Black Irish.' "

"What do you do to help him?" I asked. After a long pause, he said, "I take him fishing."

"And when that doesn't work?" I asked.

"You better go and see your own brother," he answered.

Wanting to see him in perspective when I saw him, I stood still until I could again see the woman in bib overalls marveling at his shadow casting. Then I opened the door to the room where they toss the drunks until they can walk a crack in the floor. "His girl is with him," the sergeant said.

HE was standing in front of a window, but he could not have been looking out of it, because there was a heavy screen between the bars, and he could not have seen me because his enlarged casting hand was over his face. Were it not for the lasting compassion I felt for his hand, I might have doubted afterwards that I had seen him.

His girl was sitting on the floor at his feet. When her black hair glistened, she was one of my favorite women. Her mother was a Northern Cheyenne, so when her black hair glistened she was handsome, more Algonkian and Romanlike than Mongolian in profile, and very warlike, especially after a few drinks. At least one of her great-grandmothers had been with the Northern Cheyennes when they and the Sioux destroyed General Custer and the Seventh Cavalry, and, since it was the Cheyennes who were camped on the Little Bighorn just opposite to the hill they were about to immortalize, the Cheyenne squaws were among the first to work the field "Over after the battle. At least one of her ancestors, then, had spent a late afternoon happily cutting off the testicles of the Seventh Cavalry, the cutting often occurring before death.

This paleface who had stuck his head out of the booth in Weiss's cafe and yelled "Wahoo" was lucky to be missing only two teeth.

Even I couldn't walk down the street beside her without her getting me into trouble. She liked to hold Paul with one arm and me with the other and walk down Last Chance Gulch on Saturday night, forcing people into the gutter to get around us, and when they wouldn't give up the sidewalk she would shove Paul or me into them. You didn't have to go very far down Last Chance Gulch on Saturday night shoving people into the gutter without getting into a hell of a big fight, but she always felt that she had a disappointing evening and had not been appreciated if the guy who took her out didn't get into a big fight over her.

When her hair glistened, though, she was worth it. She was one of the most beautiful dancers I have ever seen. She made her partner feel as if he were about to be left behind, or already had been.

It is a strange and wonderful and somewhat embarrassing feeling to hold someone in your arms who is trying to detach you from the earth and you aren't good enough to follow her.

I called her Mo-nah-se-tah, the name of the beautiful daughter of the Cheyenne chief, Little Rock. At first, she didn't particularly care for the name, which means, "the young grass that shoots in the spring," but after I explained to her that Mo-nah-se-tah was supposed to have had an illegitimate son by General George Armstrong Custer she took to the name like a duck to water.

Looking down on her now I could see only the spread of her hair on her shoulders and the spread of her legs on the floor. Her hair did not glisten and I had never seen her legs when they were just things lying on a floor. Knowing that I was looking down on her, she struggled to get to her feet, but her long legs buckled and her stockings slipped down on her legs and she spread out on the floor again until the tops of her stockings and her garters showed.

The two of them smelled worse than the jail. They smelled just like what they were - a couple of drunks whose stomachs had been injected with whatever it is the body makes when it feels cold and full of booze and knows something bad has happened and doesn't want tomorrow to come.

Neither one ever looked at me, and he never spoke. She said, "Take me home." I said, "That's why I'm here." She said, "Take him, too."

She was as beautiful a dancer as he was a fly caster. I carried her with her toes dragging behind her. Paul turned and, without seeing or speaking, followed. His overdeveloped right wrist held his right hand over his eyes so that in some drunken way he thought I could not see him and he may also have thought that he could not see himself.

As we went by the desk, the sergeant said, "Why don't you all go fishing?"

I did not take Paul's girl to her home. In those days, Indians who did not live on reservations had to live out by the city limits and generally they pitched camp near either the slaughterhouse or the city dump. I took them back to Paul's apartment. I put him in his bed, and I put her in the bed where I had been sleeping ing, but notbut not until I had changed it so that the fresh sheets would feel smooth to her legs.

As I covered her, she said, "He should have killed the bastard."

I said, "Maybe he did," whereupon she rolled over and went to sleep, believing, as she always did, anything I told her, especially if it involved heavy casualties.

By then, dawn was coming out of a mountain across the Missouri, so I drove to Wolf Creek.

IN those days it took about an hour to drive the 40 miles of rough road from Helena to Wolf Creek. While the sun came out of the Big Belt Mountains and the Missouri and left them behind in light, I tried to find something I already knew about life that might help me reach out and touch my brother and get him to look at me and himself. For a while, I even thought what the desk sergeant first told me was useful. As a desk sergeant, he had to know a lot about life and he had told me Paul was the Scottish equivalent of "Black Irish." Without doubt, in my father's family there were "Black Scots" occupying various outposts all the way from the original family home on the Isle of Mull in the Southern Hebrides to Fairbanks, Alaska, 110 or 115 miles south of the Arctic Circle, which was about as far as a Scot could go then to get out of range of sheriffs with warrants and husbands with shotguns. I had learned about them from my aunts, not my uncles, who were all Masons and believed in secret societies for males. My aunts, though, talked gaily about them and told me they were all big men and funny and had been wonderful to them when they were little girls. From my uncles' letters, it was clear that they still thought of my aunts as little girls. Every Christmas until they died in distant lands these hastily departed brothers sent their once-little sisters loving Christmas cards scrawled with assurances that they would soon "return to the States and help them hang stockings on Christmas eve."

Seeing that I was relying on women to explain to myself what I didn't understand about men, I remembered a couple of girls I had dated who had uncles with some resemblances to my brother. The uncles were fairly expert at some art that was really a hobby - one uncle was a watercolorist and the other the club champion golfer _ and each had selected a profession that would allow him to spend most of his time at his hobby. Both were charming, but you didn't quite know what if anything you knew when you had finished talking to them. Since they did not earn enough money from business to make life a hobby, their families had to meet from time to time with the county attorney to keep things quiet.

Sunrise is the time to feel that you will be able to find out how to help somebody close to you who you think needs help even if he doesn't think so. At sunrise everything is luminous but not clear.

Then about 12 miles before Wolf Creek the road drops into the Little Prickly Pear Canyon, where dawn is long in coming. In the suddenly returning semidarkness, I watched the road carefully, saying to myself, hell, my brother is not like anybody else. He's not my gal's uncle or a brother of my aunts. He is my brother and an artist and when a four-and-a-half-ounce rod is in his hand he is a major artist. He doesn't piddle around with a paint brush or take lessons to improve his short game and he won't take money even when he must need it and he won't run anywhere from anyone, least of all to the Arctic Circle. It is a shame I do not understand him.

Yet even in the loneliness of the canyon I knew there were others like me who had brothers they did not understand but wanted to help. We are probably those referred to as our brothers' keepers," possessed of one of the oldest and possibly one of the most futile and certainly one of the most haunting of instincts. It will not let us go.

Reprinted by permission of the University of Chicago Press from A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean. Copyright © 1976 by the University of Chicago.

This story is excerpted from A River Runs Through It, a collection of autobiographical fiction by NormanMaclean '24. The setting is the Big Blackfoot, theriver that "runs through it," in western Montanawhere Maclean grew up (in the largest meaning of thephrase) before coming to Dartmouth. His brotherPaul was a member of the Class of 1928.In a strange novel called The Professor's Wife athinly disguised David Lambuth, Dartmouth's legendaryprofessor of English, says of Maclean: "He lacksthe reliability that would make a good professor, and

I do not think the college is the best place for a poet todevelop in. But he has shown me chapters of a novelhe is writing now, and it seems to me the best poeticprose I have ever read." That was in 1928. At the timeof his retirement in 1973 Maclean was WilliamRainey Harper Professor of English at the Universityof Chicago, the only member of the Chicago facultyto be cited three times for excellence in undergraduateteaching. Now, in A River Runs Through It (publishedthis spring by the University of Chicago Press) that"poetic prose" has come to light at last.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

Feature

Feature231 Years for Dartmouth

June 1976 -

Feature

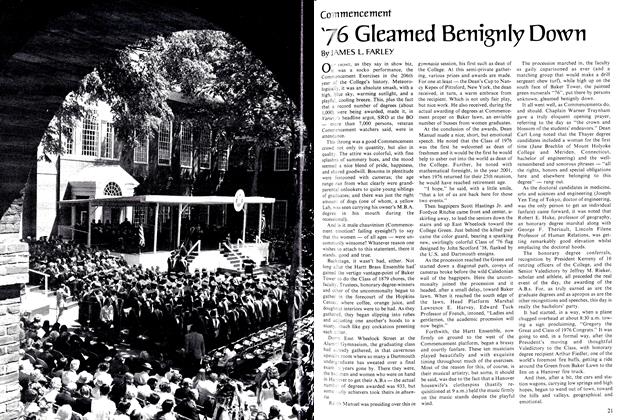

FeatureCommencement

June 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Article

ArticleCollege with an Upper-case "C"

June 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

June 1976 By ALEXANDER D. VARKAS JR., STEVEN D. BLECHER

Features

-

Feature

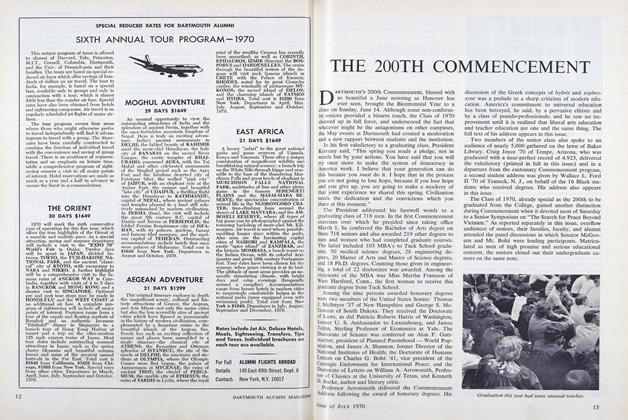

FeatureTHE 200TH COMMENCEMENT

JULY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureAdvocate for the Aging

APRIL 1972 -

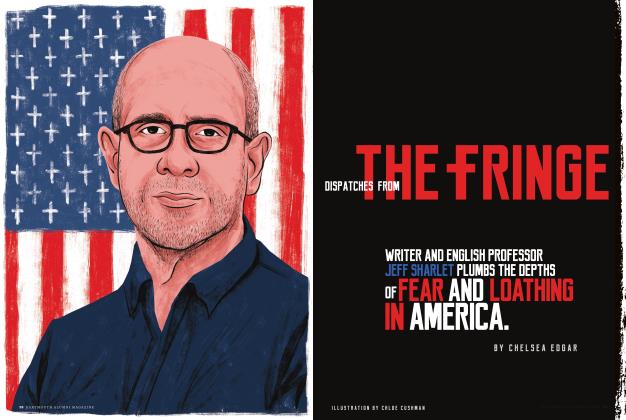

FEATURES

FEATURESDispatches from the Fringe

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2023 By CHELSEA EDGAR -

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

MAY 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60