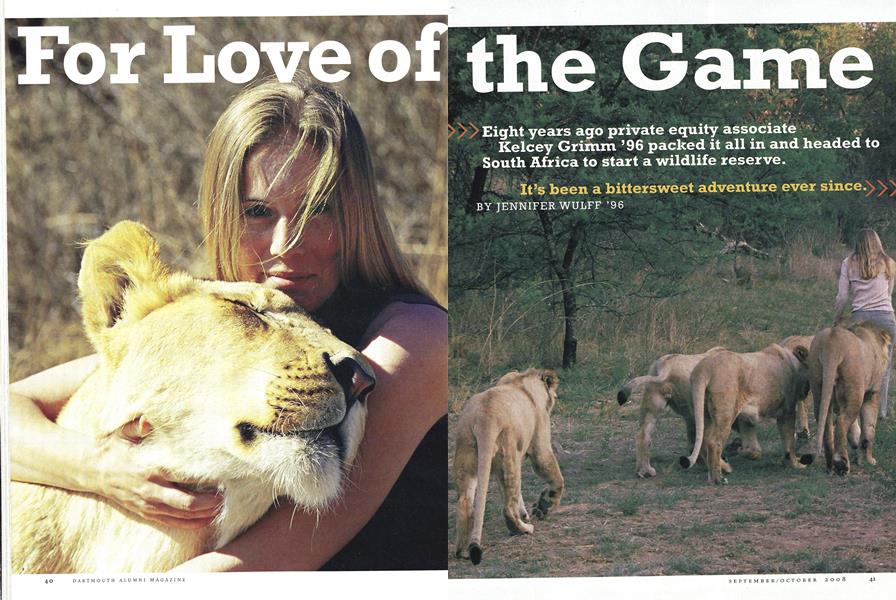

For Love of the Game

Eight years ago private equity associate Kelcey Grimm ’96 packed it all in and headed to South Africa to start a wildlife reserve. It’s been a bittersweet adventure ever since.

Sept/Oct 2008 Jennifer Wulff ’96Eight years ago private equity associate Kelcey Grimm ’96 packed it all in and headed to South Africa to start a wildlife reserve. It’s been a bittersweet adventure ever since.

Sept/Oct 2008 Jennifer Wulff ’96Eight years ago private equity associateKelcey Grimm '96 packed it all in and headed toSouth Africa to start a wildlife reserve.It's been a bittersweet adventure ever since.

She wouldn't trade the nights for anything in the world. Deep in the African bush, 45 minutes from the nearest paved road, Kelcey Grimm falls asleep to the blare of hundreds of frogs croaking from the small river outside her window, jackals cackling to each other in the pitch darkness and bush babies wailing like an army of colicky infants. "Its so loud here at night," she says. "But I wouldn't even think of wearing earplugs. I love it."

As the sun begins its climb each morning over the mountains that nestle Enkosini (Zulu for "place of kings"), Grimm's 20,000-acre game reserve, the nighttime noises fade and a new sound wakes her up. It comes from the half-dozen Vervet monkeys that hang around the house. They screech at each other and scamper back and forth across the tin roof of Grimm's small home at the excitement of a new day. If she's not careful, they'll come in and steal whatever food they can find. "You leave a window open more than a crack, and they'll get in and ransack the whole place," says Grimm, 34, a fit blonde with a sprinkling of freckles brought out by the African sun. "The naughty little creatures are very smart and very curious. I live in a cage and the animals run free, basically."

No matter how often sleep is disrupted or her breakfast is pinched by a primate, Grimm is devoted to this life she's come to love since quitting a successful career in venture capital and moving to South Africa eight years ago.

It hasn't been easy, though. For one thing, her modest, refurbished old farmhouse has no running water or electricity (some solar panels allow for some electronics and evening lamps) and the nearest town, Lydenburg, is more than an hour away.

Then there are the other humans, who seem determined to send this headstrong American conservationist packing. Poachers set traps to steal Grimms animals, drug smugglers infiltrate her property to cut down the khat plants (to make an amphetamine-like drug widely trafficked in Somalia) and arsonists set fires purely for malicious reasons. The locals have become such a problem that she needs to carry a gun at all times. "In the house I have a rifle, and I carry a pistol on the grounds," she says.

And there are the legal battles. Grimm and her business partner Greg Mitchell, 42, have been in a three-year fight with the De Beers cartel, which is seeking to take the land for diamond mining, and a local community has also filed a land claim. (Since the end of apartheid blacks have been able to file claims on land that may once have been theirs but was taken under white rule.) Grimm, who suspects that the claim is related to De Beers' interest in the land, has a strong case to fight the claim, but it's difficult to not get discouraged. "With any cause, you throw yourself into it and you do the best you can, but sometimes it just breaks you," says Grimm. "It's so exhausting, so emotionally exhausting."

Grimm can't focus her energy on worrying about these looming problems, though. There's too much work to be done. "I'm busy about 14 to 16 hours every day," she says. On any given day at Enkosini fencing needs to be put up, snares (along with some unlucky victims) need to be collected, roads need to be cleared, bridges need to be built and, of course, those fires, which burn out 20 percent of the property every year, need to be stopped. On top of managing Enkosini's 20 to 30 employees, she and Mitchell need to make sure the six to 20 rolling volunteers who come to the reserve for a working vacation are happy. She also needs to care for injured animals and help with the reintroduction of all the species being released on the land. "There is no 'me' time," she says. "There's barely time to sleep."

Most of Enkosini's money is earned from Grimm booking volunteers for 15 other reputable eco-tourism destinations in the area (this generally means very little contact with wildlife, as in "look, don't touch"). With up to 300 e-mails a day to address and the volunteer program Web site to maintain, it's a job that takes four to six hours every day on top of her manual and legal work at Enkosini. But the 20 percent commission she earns "is what keeps my own baby going," says Grimm.

Maternal Instincts

That Grimm would wind up in Africa caring for wild animals was not predictable, even though she grew up with one. Peter Grimm, her father and a Vietnam War vet, owned a few Seattle area Lincoln-Mercury dealerships and bought a cougar cub to promote the Cougar brand at his flagship store. Named Rascal, the cougar became a family pet and even accompanied Kelcey to school for show and tell when she was 8 or 9. "He was just a baby," recalls Grimm. "Teeny, teeny and covered in spots." He lived with the family for two years before he was sent to a sanctuary. "I think having Rascal gave me a comfort with working with wild animals, and big cats in particular," says Grimm. "It shaped me."

She's also quick to point out that she and her parents are now wiser about such things. They vehemently oppose using wild animals for entertainment purposes.

Following graduation Grimm spent four years in the highpressure world of private equity working as an associate for Summit Partners in Palo Alto, California. "It was a really fun time and a really fun industry," she says. "It's amazing to me that as a 25-year- old I was sitting on the boards of companies and pitching billiondollar ideas." In 2000 she decided to take a six-month sabbatical to travel to Africa, India and Asia. She first hit Kenya, then made her way to Tanzania, Uganda and East Africa, meeting up with a few pals along the way, including Heidi Taylor '96, then a Peace Corps volunteer. Grimm's mother, Camilla, joined her in South Africa, and the two women headed down the coast toward Cape Town when Camilla found a place worthy of a detour. "My mom was like, 'Look at this place—you can play with lion cubs there!'" says Grimm. "It was about eight hours off track but we had to go."

Spending just a day at Camorhi, which labeled itself as a breeding project facility, Grimm became "totally hooked" while bottle-feeding and cuddling the cubs. "It was such a unique and special experience—who wouldn't want to play with lion cubs?" she says. It also pulled at her heartstrings. Grimm and the other tourists there were told that the babies had been orphaned and needed hand-rearing. She wanted to help out and decided to extend her stay for another month or two.

It wasn't long into her work with the cubs, however, that she suspected something was amiss. "I'd seen a couple of the older lions there disappear and I got curious," she says. "Once the new- ness wore off, I started to ask questions like, 'Why are we allowed to have contact with all these animals? What exactly happened to their mothers? Where are they going when they grow up?' " The answers weren't pretty. It turned out that the lions at Camorhi were not being sent on their merry way to zoos or reserves but raised for the purpose of being shot and killed by trophy hunters.

The canned hunting industry of South Africa earns big money for places such as Camorhi. Foreigners plan visits to the country for the sole purpose of shooting a lion to put its head up on their walls. And they'll pay upwards of $1OO,OOO for the privilege. In the wild, "a search for a lion could take weeks," says Mitchell. "For someone who can afford to pay that kind of money, time is of the essence. So these groups will go out beforehand and drug the lion, then their customer will come along and they'll say, 'Oh, there's your lion sleeping under a tree.' " With most of the lions having little fear after being raised by humans anyway, it's not so much a hunt as it is a grander version of shooting fish in a barrel.

Grimm knew she wouldn't be able to fight the whole industry, but at the very least she wanted to expose the issue—and save the eight lions she was caring for. "I was their matriarch," she says. "They respected me, they followed me. There was a love there that was amazing." She was determined to protect her babies from harm. "I had this American optimism, like, 'We can make a difference,' " says Grimm. She figured out a way to buy the lions from the owners of Camorhi, but first she needed some land to put them on. That proved to be a much bigger endeavor than she expected.

She returned to the States intent to find funds to buy a parcel of land she found about 400 kilometers northeast of Johannes- burg. "I cashed in my 401k, sold every stock I had, every piece of furniture, and put together all my savings, even babysitting money from high school," she says. 'All of it went into the property. We laugh now because I kept saying, 'Mitch, it's just money!' But it's an unbelievable amount of money to do what we've done."

Grimm also got a near-match loan from her parents' retirement savings. "It's hard to say no when your daughter is out to help save animals," says Camilla, a former banker herself. So with a total of $500,000 and the help of Mitchell, whom she lives with at Enkosini, Grimm bought her first 5,000 acres and began the dream she never knew she had.

From the Ground Up

Enkosini, a nonprofit with 501(c) status, was just a piece of overgrazed farmland when Grimm bought it, unfit for the indigenous beasts that had freely roamed it 50 years ago. In fact, while they were busy taking down hundreds of kilometers of cattle fencing and putting up a new 6-foot high steel perimeter suitable for the anticipated wildlife, Grimm and Mitchell had to let nature run its course for five years before reintroducing any animals to the property. "I'll never forget the first time we saw a chameleon on the land," says Grimm, who has bought three more parcels through the years. "A chameleon is a sign of a really healthy environment. It sounds small, but it was such an exciting moment."

Now there's a lot more wildlife she's excited about. The property is still in its beginning stages, but there are already dozens of species that roam the plains and bush, including baboon, African wildcat, leopard, brown hyena, kudu, duiker, warthog and crocodile. A three-phase release of more species for the next couple of years will include zebra, wildebeest, impala, giraffe, rhino and cheetah. Reintroducing wildlife is a complicated business. It's not just a matter of letting the creatures loose to do their own thing. Reserves are highly regulated in South Africa—"lt's a lot easier to kill animals than it is to save them," says Grimm—so an environmental consultant visits the property each year to make sure everything is balanced.

To help her keep the numbers straight, Grim maintains an Excel spreadsheet even Darwin might find confusing. Taking into account how many herbivores the vegetation on the land can support (the plant life requires its own 80-plus item spreadsheet), as well as how much breeding each species will do and how many can be expected to die annually, the math isn't for the faint of heart. "Say we're allowed to have 100 zebras," says Grimm. "You'd never bring in 100 because they multiply like crazy. You also have to balance the male and female ratio because you need a certain amount of females per male, but you also need enough males to compete with each other."

And should they overpopulate? Sadly, a lot of excess animals at reserves are culled (a less gruesome word for killed), but Grimm works hard to arrange trades of animals with other reserves, depending on who needs what. She'll buy others at auction from larger reserves such as nearby Kruger National Park.

As for her own lions, now living at a reserve in Johannesburg, it's unlikely they'll ever roam the plains of Enkosini. Grimm went through a lengthy and costly court battle fighting for the necessary permitting, but her request was denied. "Why they didn't give her the permit was absolutely a personal issue. It was sheer malice and spite on the part of conservation officials," says Chris Mercer, a retired lawyer and national director of the Campaign Against Canned Hunting. "To me, she's one of the most courageous people I've ever met, but I don't think 'hatred' is too strong a word for what they thought of her. They're not only in favor of canned hunting, they're part of it, and she was threatening the whole industry." As Mercer tells it, Grimm didn't even stand a chance. "It would be the equivalent of a person in America trying to fight big tobacco," he adds. "The dice were heavily against her." And there was no point in relying on the legal system to deliver justice. "One of the judges actually fell asleep during arguments," says Grimm. "That's what we were dealing with."

As much as she misses them, trying to save eight lions led her to an even bigger purpose here in South Africa. "I'm not exceptionally spiritual," she says. "But there's something about the way everything happened that made me feel as though this was meant to be."

Her goal now? It's all about the land. If she can save precious habitat from mining and other industry, she can ultimately protect thousands of animals. "I went into this as a real bunny-hugger, but I'm less emotionally driven than conservation-driven now. As much as I love working with individual species, I've realized now that it's all about protecting habitat. Everything else flows from that. If you're able to keep the land wild and natural you're able to protect a whole ecosystem."

She has impressed even veterans of the conservation field with her purpose and dedication. "She's become a leading light in conservation in South Africa," says Mercer. "It's a result of Kelcey and others like her that we now have a viable animal welfare lobby here."

She's also made an impression on her old Dartmouth friends. "I remember meeting her on the Green in the middle of winter once," says friend Erica Greenwood '96, "and she comes walking across in high heels and a dress—do you remember anyone wearing a dress at Dartmouth?—and now she barely even showers. But we weren't that surprised she's followed this path. She's always been the political activist of the group."

The former Kappa Kappa Gamma sister faces tough challenges in making her endeavor succeed. Although Enkosini brings millions of dollars into South Africa every year, the government would prefer the land be used for diamond mining or development. "You have to decide ahead of time whether you're going to be in community work or wildlife work because the two are in contrast with each other," says Grimm. As much good as Grimm does, the mining industry is a bigger force. "De Beers believes we have diamonds on our property, and we've been fighting them for three years. It's been very difficult and very expensive. Interestingly enough, the whole land claim matter never came up until they came into the picture," says Grimm. "They're actually using land claims in order to acquire more land. I'm positive that De Beers is putting pressure on this community to claim it, and then they can just buy it without us fighting them."

Even though she commissioned a "very thorough" 60-page research report from a University of Pretoria archivist stating that the land has no legitimate claims, Grimm will not be surprised if the evidence is ignored. "There's a phrase here," says Grimm. "In Africa there's no right and wrong—only winners and losers. And it's so true."

She sounds weary when discussing the regions many problems. "I've become so jaded here," says the former idealist. Fourteen years after the end of apartheid, South Africa remains in a troubled state of transition, with unqualified leaders and corrupt government officials. The crime rate seems to get only worse. At each of the neighboring farms surrounding Enkosini someone's been killed or raped or pistolwhipped. But Grimm tries to see the good in everyone. "Even though I have more anger in me today, I'm always hoping not to be disappointed. When I start to get a little harsh, I remember that education is really at the heart of it all. And the education system here needs so much help. Our local school has a huge sign in the girls' bathroom that says 'Rape is Not a Crime.' How do you succeed in a country like that?"

Despite the many challenges, Grimm remains determined to continue on her mission. "There's always hope until it happens," she says of the possibility that Enkosini could be taken from her. In the meantime, she happily gets up with those monkeys, each day. "Because I believe in this, living here is not such a burden," she says. "This will always be my life. That will never change. It's difficult and challenging and crazy, but I keep coming back for more."

A Wild Life (clockwise from lower left) The restored farmhouse Grimm calls home; Grimm and friend in Tanzania; rainy season on the Enkosini plains; volunteers help build a bridge in 2005; a kudu skull in a snare is a stark reminder of poaching. Previous pages: Madoda, Grimm and the pride.

"She's become a leading light in conservationin South Africa," says one activist. "We now have a visible animal welfare lobby here."

LENDING A HAND Kelcey Grimm's Enkosini Eco Experience offers paying volunteers the chance to work on a variety of wildlife conservation, rehabilitation and research projects in Southern Africa, A variety of reserves and sanctuaries participate, including her own. To volunteer at Enkosini, where Grimm works and lives, volunteers pay $995 for a minimum two-week visit. They're provided food and accommodations in exchange for help with all the work that goes into building and running a reserve. "It's got a Habitat for Humanity element to it, but we're not slave drivers," says Grimm. "People work as much as they want to. Then they can go swimming in our waterfalls, hiking, horseback riding, and we take everyone on a three-day trip to Kroger National Park," For more information, click on enkosiniecoexperience.com.

JENNIFER WULFF lives in Norwalk, Connecticut, with her husband and daughter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

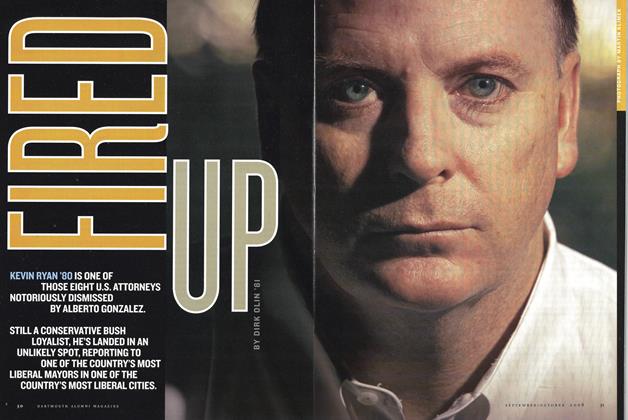

FeatureFired Up

September | October 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureIn Their Own Words

September | October 2008 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSWeathering the Storm

September | October 2008 By Diederik Vandewalle

Jennifer Wulff ’96

-

Feature

FeatureGame Changer

NovembeR | decembeR By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

FEATURE

FEATUREBehind the Scenes

MARCH | APRIL 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

FEATURE

FEATUREUpside-Down World

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNo Script Required

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureSafe Haven

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

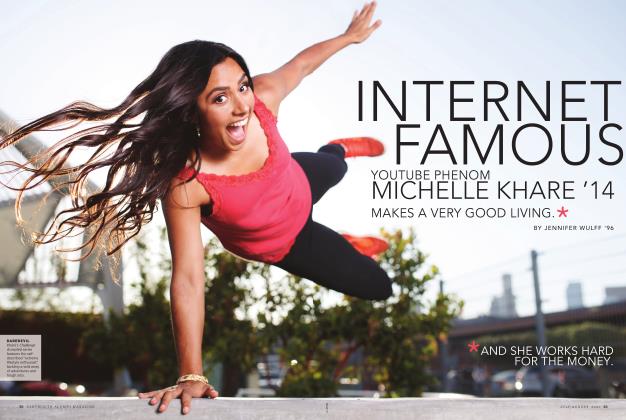

Cover Story

Cover StoryInternet Famous

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBenjamin K. Pierce 1812

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

OCTOBER 1984 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureA Shapely Punctuation Mark

July 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

APRIL 1997 By Karen Endicott -

COVER STORY

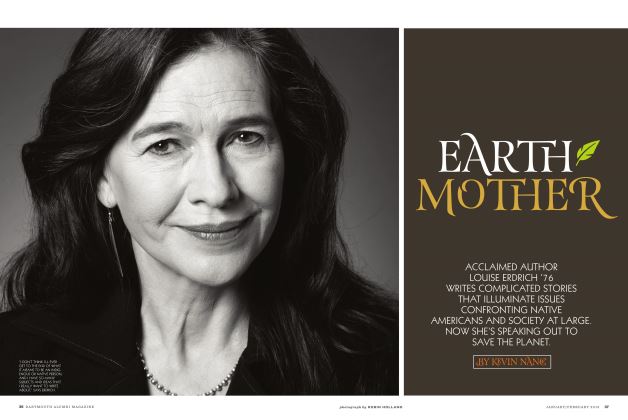

COVER STORYEarth Mother

JAnuAry | FebruAry By KEVIN NANCE