The Webster Papers Burn this letter, said D.W. His confidant disobeyed and history is the richer for it.

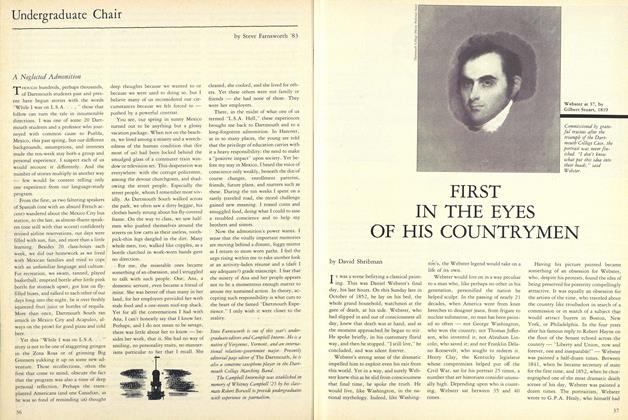

ON March 11, 1843, Daniel Webster, then Secretary of State, wrote Nichloas Biddle a "strictly private & confidential" letter about the political climate in John Tyler's Washington. Before Webster signed the note, written in his scratchy and hurried hand, he implored: "When you have read this burn it."

Because Biddle, a close friend of Webster and a fellow Whig, did not burn the letter, it ended up in the Biddle Papers in the Library of Congress and eventually on one of the 41 reels of microfilm assembled for the Daniel Webster Papers by a Dartmouth research team and issued in 1971. Had Biddle and several other recipients of letters from Webster actually followed the orders to burn confidential accounts of politics and diplomacy, historians would have a far less rich view of Daniel Webster and of America in the four decades between his election to Congress from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1812 and his death near the swamps and creeks of his Marshfield, Massachusetts, home in 1852.

There are few universal truths in history and because each generation looks at the past from its own perspective, history often is rewritten by each generation. Items like the letter to Biddle, with its complaints about the way Tyler, a Virginian, handled patronage matters, are the natural resources of history. Historians mine them and extract the items on which they will base their new interpretations of the past. The letter to Biddle is one of 176 Webster wrote to the controversial head of the Bank of the United States and one of tens of thousands of pieces of Websteriana being studied by Charles M. Wiltse and the staff of the Papers of Daniel Webster. Like a deep mineral lode, they will be valuable long after today's interpretations of history are outdated.

Last month the second volume of the letterpress edition of the Webster Papers, covering Webster's personal corres-pondence from 1825 to 1829, was published by the University Press of New England. Within the next few years 12 more volumes, dealing with the remainder of Webster's personal correspondence, his legal and diplomatic papers, and his speeches, will become available. While the microfilm edition of the Webster Papers provides an exhaustive view of Webster for serious scholars who can endure hours of work at a microfilm reader, the letterpress volumes will include only about ten per cent of the available Webster documents - which is still, Wiltse says, "more than you'll ever want to know about Daniel Webster."

Editing the documents in the Webster Papers down to 14 volumes is a task not unlike panning for gold. In a suite of rooms lined with dusty books, piles of manila document envelopes, and stern portraits of Webster, editors sift through photocopies of Webster's letters and related documents and cull the most repre- sentative as well as the most valuable nuggets from the collection. Wiltse, an eminent historian known for his work on Jefferson as well as his monumental three-volume life of John C. Calhoun, assumed the job in 1967. The task of editing Webster's personal correspondence down to seven volumes has fallen to him and to Harold D. Moser, the associate editor of the Webster Papers, who won national recognition for his documentary editing last year. Kenneth E. Shewmaker, an associate professor of history at Dartmouth, is at work on Webster's diplomatic correspondence during his two terms as Secretary of State, while Alfred Konefsky and Andrew King are editing Webster's legal papers at the Harvard Law School in Cambridge.

THE work is not being undertaken out of worshipful antiquarianism. Webster is a controversial figure who played a central role in 19th-century America. There were giants in the Congress then and Webster, along with his contemporaries John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Thomas Hart Benton, were probably more influential than most of the men who lived in the White House in the era. "You can't get to the roots of understanding what makes America tick in this period without understanding these individuals," says Wiltse, a 69-year-old gray-haired man who talks as if he once looked down from the visitors' gallery and listened in awe to the Old Romans of the Senate. "This was a period of sweeping transition in America, when the 'United States' became a singular noun and not a plural noun. The influence of Webster and his generation was immense."

It was the period when America began its frenetic leap toward modernity, when the era of knee breeches and cocked hats gave way to the dress and the thinking of modern America. The railroad, the factory towns, even the women's movement and the second two-party system, began to emerge and wield their influence in this period. Webster was one of the spokesman of the era. He was a leading figure in many of the most significant Supreme Court cases in our history (not the least of which was Dartmouth College v. Woodward in 1819) and was one of America's greatest Secretaries of State.

Webster was a great orator in the golden age of oratory and efforts to collect his speeches began more than two decades before his death. An edition of Webster's Speeches and Forensic Arguments was published as early as 1830, when he rallied the forces of nationalism with his famous Second Reply to Hayne. Other editions followed, including Massachusetts diplomat Edward Everett's six-volume Worksof Daniel Webster in 1851.

In January 1853, less than three months after Webster's death, his literary executors distributed a circular asking for copies of his works and correspondence and requesting leads for finding other Webster documents. His son Fletcher, who had served with him in the State Department in the 1840s, used Webster's own personal files and the papers assembled by the literary executors to fashion a two-volume edition of Webster's Private Correspondence. His selections, published in 1857, were made with what Wiltse calls "filial piety"; the result was a highly unreliable collection of doctored documents. The original papers, however, were returned to the executors and divided between Edwin D. Sanborn, Webster's nephew by marriage and a Dartmouth professor and librarian, and Peter Harvey, a close friend of Webster. Harvey's letters were given to the New Hampshire Historical Society one hundred years ago and Sanborn's letters were bequeathed to Dartmouth by Edwin Webster Sanborn, Class of 1878.

Most of the documents which were used to prepare George Ticknor Curtis' Life ofDaniel Webster (1870) and which survived a fire in 1881 were delivered to the Library of Congress in 1903. Most of the remainder have been acquired by the Dartmouth College Library and are housed in the College Archives. Two other collections of Webster's writings and speeches were published before the microfilm edition was released in 1971.

WHEN Wiltse left his job as Chief Historian for the United States Army Medical Service in 1967, however, very little had been assembled. Six thousand letters to libraries, historical societies, and other institutions and individuals possibly having letters and documents by or about Webster had been distributed before Wiltse's arrival at Dartmouth. He pressed the search for documents, and field searchers were employed throughout New England and in Washington, Boston, Ottawa, and London. Documents were found in courthouses, barns, and attics, and even old trunks, desks, and vaults yielded valuable items.

Some years ago, in fact, Wiltse came across an outdated dealer's catalogue which listed the collection of papers of the Haskins family, Boston merchants and contemporaries of Webster. Although a single Webster item may draw as much as $500, the entire collection of the Haskins papers - all 1,500 items - was listed at only 5135. Wiltse called the dealer in Connecticut and learned that the collection had not yet been sold. The College library purchased the collection (at the original price) and discovered drafts of four letters to Webster, letters which concerned a lawsuit involving the Haskins and correspondence with other notables of the era.

Once the documents were on hand, then began the wearisome process of identifying writers and recipients of letters, deciphering 19th-century handwriting (difficult by any scale, though less difficult if the letter was written by a professional copier), and labeling each item. Each document was placed in a large envelope with the date and other pertinent information on the outside. When Wiltse determined he had assembled all the items he was likely to find, the documents were placed in chronological order, meticulously indexed, and filmed by University Microfilms of Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The microfilm edition was prepared from photocopies so the pages of the documents could be re-arranged without endangering the original documents, a useful technique because correspondents often wrote on margins or on the cover of letters to save expensive paper and postage. Each of the 41 reels of the microfilm edition of the Webster Papers has about 2,000 frames (an average letter takes three or four frames), and there are more than 50 reels of legal papers and another 400 reels of Department of State documents from Webster's two terms as Secretary of State. Many of the State Department documents, however, involve routine department business and are not particularly important to a study of Webster.

Today the actual documents are scattered about North America, with some in Great Britain. Dartmouth's collection of 1,800 documents is rich in the period before 1820 and includes the notes and draft of Webster's argument in the Dartmouth College Case. The New Hamp- shire Historical Society has 2,500 documents and others, including the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the Massachusetts Historical Society, collections at Yale, Harvard,Brandeis. and the University of Virginia, as well as the British Public Record Office, have items of Websteriana.

Saul K. Padover, a leading Jefferson scholar, once said that working on Jefferson's papers was the central event of his life; indeed, he said that he needed Jefferson far more than Jefferson needed him. But Wiltse, the latest collector of Webster documents, did not come to Dartmouth out of a consuming interest in Daniel Webster but rather out of a long-term interest in the period between the adoption of the Constitution and the Civil War. Now, of course, he knows Daniel Webster thoroughly and he says he has a "vague affection" for him. "He'd be a delightful fellow to go fishing with," Wiltse comments. "I don't always agree with him but I can see what he was doing and how he was going'about it."

"Calhoun was far more austere and ascetic," he continues, peering out from behind large gray glasses. "Webster liked people. He never lost a friend. He made them easily and he kept them. He corresponded with college classmates until the time of his death."

Because the Webster documents themselves are so voluminous the letterpress editions probably will be used most often by future historians who seek to rewrite American history. They will rely upon Wiltse's choice of documents and they will be taking a safe gamble. He has studied the first half of the 19th century in America for nearly 50 years - a study begun when he looked about for a thesis topic while working for a graduate degree in philosophy, settled upon Thomas Jefferson, and wrote a thesis he later expanded into The Jefferson Tradition in AmericanDemocracy.

It is difficult to determine which documents will be valuable for future historians. "One can't know," Wiltse says. "One can only surmise." But he is comforted in knowing that the Webster Papers will only have to be edited once. His Calhoun biography, started over 30 years ago, will be redone sometime. "It's probably obsolete now," he remarks. But the Calhoun Papers won't be done again. They, like the Webster Papers, will form the basis for revising biographies of the two great leaders who spent careers opposing each other.

Rewriting Webster's life is one job Wiltse will not undertake. He recalls Carl Sandburg's remark that he wrote his life of Abraham Lincoln at the only time he could have done it: when he was young enough to have the energy and still old enough to be able to do it with maturity. Wiltse put in 70-hour weeks when he worked on the Calhoun series and he now believes he could not do justice to the job of writing Webster's life. "I don't have enough years left to do a life of Daniel Webster on that scale," he says. "We're picking the documents so someone else can do it."

A major biography of Daniel Webster has not been written" since Claude M. Fuess' two-volume Daniel Webster was published in 1930. At least three new lives of Webster are now in progress, though, and their authors are waiting for Wiltse and his staff to complete their work.

Picking the documents to include in the letterpress edition is itself a difficult and time-consuming undertaking. All of Webster's letters must be read and evaluated in terms of the history of the period, the people mentioned in the letter, the content of the letter, and the contribution it might make to a well-rounded understanding of Webster as a man. Each letter

is transcribed and checked carefully several times and each letter's meaning and significance are determined. "One allusion might require just a moment's thought," associate editor Moser explains, "but others might require a week's work."

The letters and documents chosen for each volume - and there will be about 375 letters in each - are annotated and often preceded by a short italicized passage explaining the background and meaning of the document. The letterpress editions are not, however, cluttered with annotations and references. Only those people not identified in either the Dictionary of AmericanBiography or the Biographical Directoryof the American Congress are identified in the books. Each volume includes a chronological list of all of Webster's known correspondence within the period covered by the volume, with the letters included within the book itself indicated by italicized type.

ALL this work on the Webster Papers has not yielded any dramatic new discoveries. By all accounts, Daniel Webster did not sleep with slave women, did not hide illegitimate children, and did not even kneel down in prayer beside the President on the White House carpet. But the work on the Webster Papers will provide the basis for a reinterpretation of Webster with a different emphasis and a new weighting of facts. Some minor items have been discovered that will readjust our view of the man who is still revered in a thousand New England hamlets and who still stands majestically in Statuary Hall on the second floor of the Capitol Building in Washington.

Webster's correspondence with Nicholas Biddle, Henry Clay, and others throws new light on the origins of the Whig Party and indicates that Biddle was a more important figure in the party's development than previously thought. Historians have long believed that Webster and Martin Van Buren, Andrew Jackson's successor in the White House and an important figure in New York state politics, cordially detested each other. The Webster Papers reveal that the two men were co-counsel in cases involving John Jacob Astor and his New York land holdings.

The Webster Papers also suggest that Webster became a presidential candidate, though not a declared one, in 1826, considerably earlier than had been thought. New light has also been thrown on the presidential campaign of 1836. Webster had been regarded as an active candidate for the presidential nomination in that year but his correspondence shows that he seems to have given up his campaign by late 1835. At that time the focus of his letters shifted from the presidential campaign to the more mundane subject of land speculation.

The papers also indicate Webster's speculation in western land between 1834 and 1838 was far more extensive than historians believed it was.

Webster had more than his share of political enemies and critics. Historian Richard N. Current wrote that the Reverend Theodore Parker of Boston sounded "like the Almighty in final judgment on a sinner" when he excoriated Webster in a sermon soon after his death. Parker portrayed Webster as a selfish and overweeningly ambitious man, one who had done more than any American to "debauch the conscience of the nation." Webster's critics, both in his own life and in the modern era, have focused on his ties with business interests, his carelessness in his personal financial affairs, and his great ambition. It is said that Webster always wanted to be rich and to be President. He was, of course, neither.

But the Webster Papers provide a fully rounded picture of Webster, an ink portrait that, like the daguerreotypes that were fashionable in Webster's time, show his fine points as well as his foibles. They show his personal financial woes and his efforts to avoid misuse of public funds. They show his exasperation with John Tyler and with John C. Calhoun and his gallantry toward ladies. They show his eloquence, his perfectly turned sentences, his uncanny ability to move men with words.

There is no way to determine how many persons really did follow Webster's solemn commandments to "burn this letter." We only know that several did not. If disobeying Webster's request be treason, then let us hope that tomorrow's historians will make the most of it.

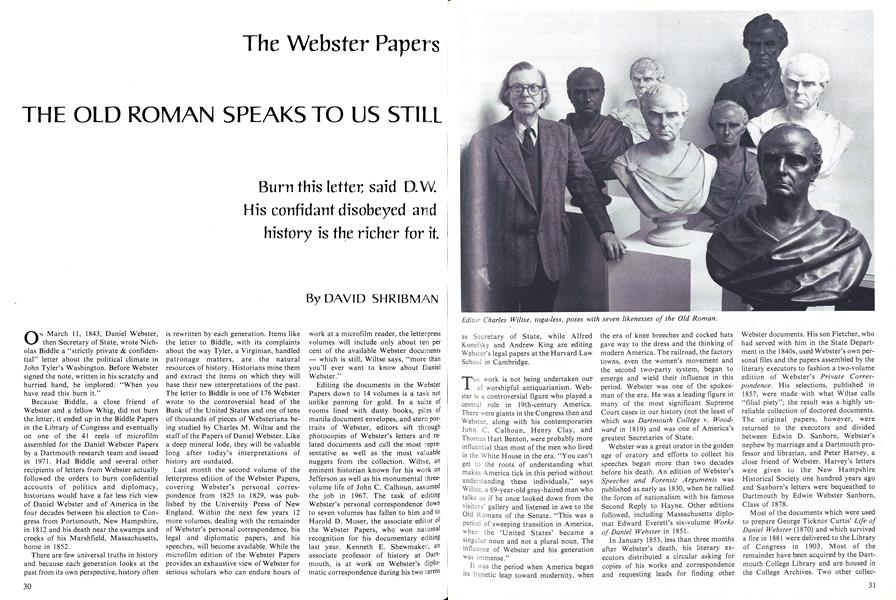

Editor Charles Wiltse, toga-less, poses with seven likenesses of the Old Roman.

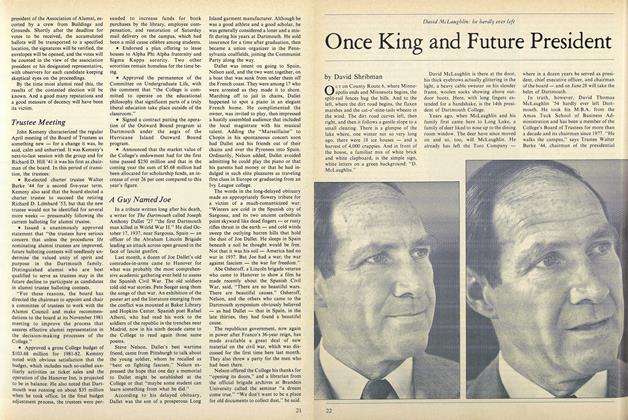

The thundrous Presence, in an 1850 daguerreotype by Southworth & Hawes of Boston

The cautionary closing: Webster to Biddle, 1843.

A history major and one of this year's undergraduate editors, David Shribmanwould just as soon live in Webster's time asany other. Next autumn he will commence studies at Cambridge University ona Reynolds fellowship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA four-and -a-half-ounce magic totem pole

June 1976 By NORMAN MACLEAN -

Feature

Feature231 Years for Dartmouth

June 1976 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Article

ArticleCollege with an Upper-case "C"

June 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

June 1976 By ALEXANDER D. VARKAS JR., STEVEN D. BLECHER

DAVID SHRIBMAN

Features

-

Feature

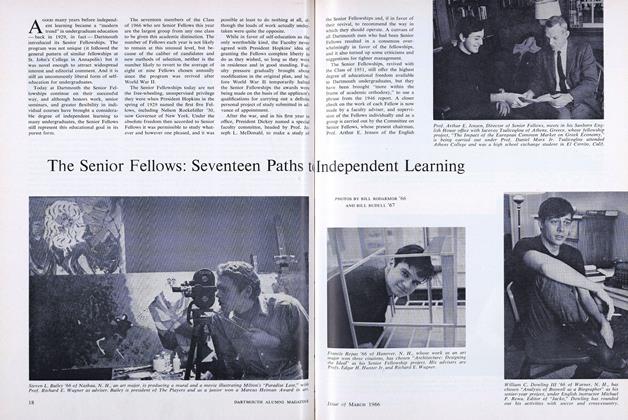

FeatureThe Senior Fellows: Seventeen Paths to Independent learning

MARCH 1966 -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

NOVEMBER 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

Jul/Aug 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

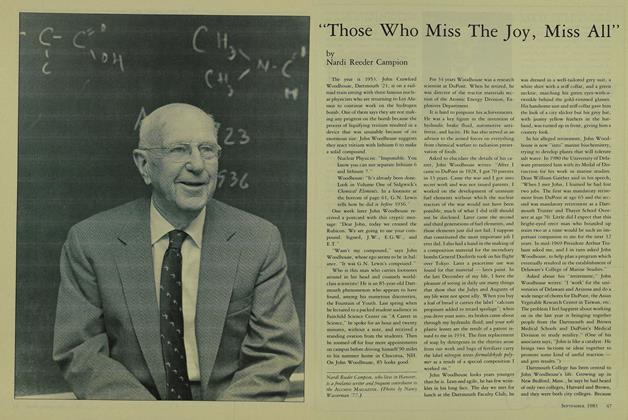

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureChanging Values in College

JANUARY 1959 By PHILIP E. JACOB