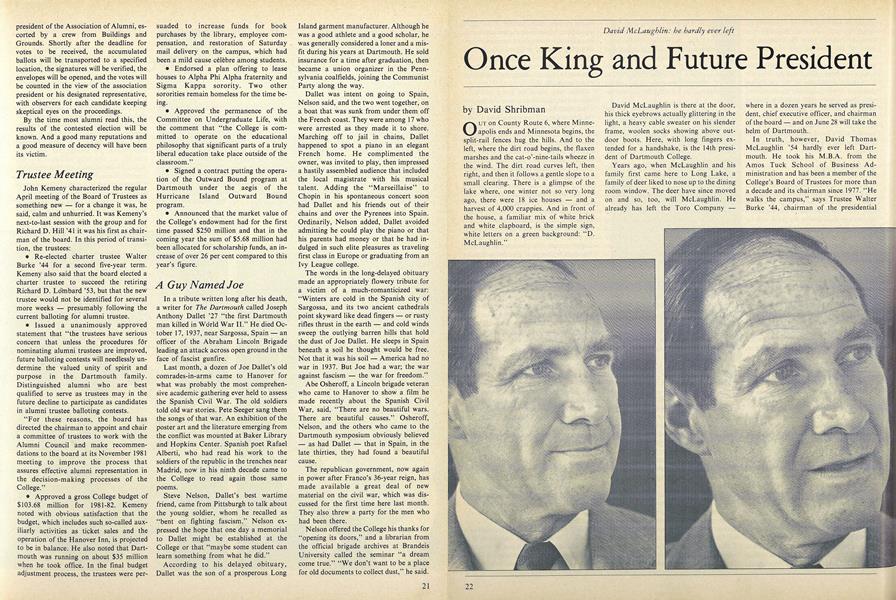

David McLaughlin: he hardly ever left

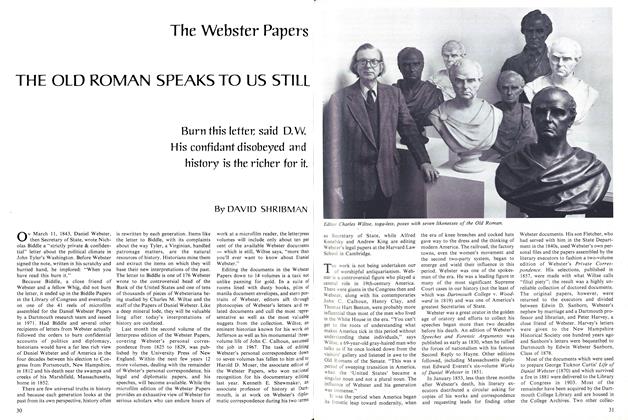

OUT on County Route 6, where Minneapolis ends and Minnesota begins, the split-rail fences hug the hills. And to the left, where the dirt road begins, the flaxen marshes and the cat-o'-nine-tails wheeze in the wind. The dirt road curves left, then right, and then it follows a gentle slope to a small clearing. There is a glimpse of the lake where, one winter not so very long ago, there were 18 ice houses and a harvest of 4,000 crappies. And in front of the house, a familiar mix of white brick and white clapboard, is the simple sign, white letters on a green background: "D. McLaughlin."

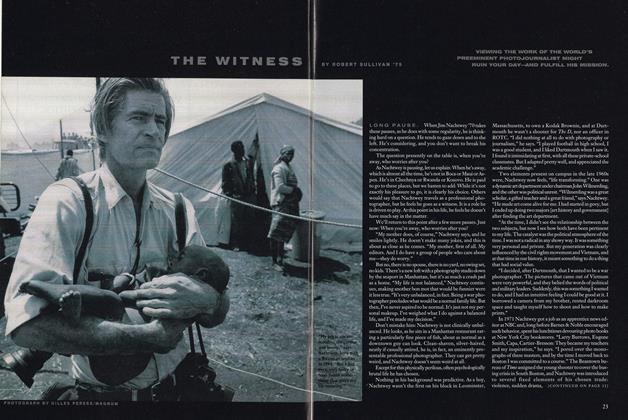

David McLaughlin is there at the door, his thick eyebrows actually glittering in the light, a heavy cable sweater on his slender frame, woolen socks showing above outdoor boots. Here, with long fingers extended for a handshake, is the 14th president of Dartmouth College.

Years ago, when McLaughlin and his family first came here to Long Lake, a family of deer liked to nose up to the dining room window. The deer have since moved on and so, too, will McLaughlin. He already has left the Toro Company - where in a dozen years he served as president, chief executive officer, and chairman of the board - and on June 28 will take the helm of Dartmouth.

In truth, however, David Thomas McLaughlin '54 hardly ever left Dartmouth. He took his M.B.A. from the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration and has been a member of the College's Board of Trustees for more than a decade and its chairman since 1977. "He walks the campus," says Trustee Walter Burke '44, chairman of the presidential search committee, "in a way few people can."

It has almost always been that way. The son of an architect, McLaughlin grew up in the furniture manufacturing city of East Grand Rapids, Michigan, and was such a standout in football that he attracted the attention of the first-term congressman from the area, Gerald R. Ford. Ford urged McLaughlin to go to Michigan, but there was something about Dartmouth the sound of it, perhaps, or the idea of all those trees - that drew him. He remembers himself now as "the greenest freshman who ever lived," a nervous young man on one of his first trips outside Michigan, but from the moment McLaughlin first saw the campus he felt at home. "It was," he says, slightly self-conscious of how maudlin it must sound, "a kind of love affair at first sight."

He moved into the triple at 410 Gile, shuffled about the campus cautiously, and then, just before the opening of classes in September 1950, he climbed the steps inside Baker Library and, in the amber light of the Tower Room, met John Sloan Dickey '29, the president of the College. Matriculation took only an instant - the quick, crisp Dickey handshake and then a few words of welcome - but the moment stayed with McLaughlin, and over the years the two became close friends, walking in the Hanover woods together and paddling through the College Grant. The Friday before the trustees met to select the successor to John G. Kemeny, McLaughlin was in Hanover, having breakfast with the Dickeys.

As a trustee during the Kemeny years, McLaughlin was one of the architects of the great changes that came with coeducation and year-round operation at Dartmouth, and he remains a strenuous supporter of those decisions. And so the first change President McLaughlin is likely to institute at Dartmouth is a small one, dating from his freshman encounter with Dickey in the hushed setting of Baker Library. During the last decade, the deans of the College, Carroll W. Brewster and then Ralph N. Manuel '58, presided over the matriculation ceremony. This September, when members of the class of 1985 line up for matriculation, David McLaughlin will be there to greet them.

It will be the first symbol of the style McLaughlin plans to bring to Hanover. His will be a visible presidency . "There is a real need," he says, "for the president to be out on campus. The president ought to eat in Thayer with the students, he ought to go to some classes, and he ought to visit with the faculty and students in different settings. You can't do that by staying in your office or by having office hours or even by saying the door's always open. You don't get a great sense of what's happening on campus by doing that."

"The president needs to be seen, and the president needs to enjoy the college," says McLaughlin.

That is the approach McLaughlin took at Toro and in his work in civic and arts activities in Minneapolis. He is, remarks Donald R. Dwight, the former lieutenant governor of Massachusetts who now is the publisher of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune, a "generator of consensus," and that plainly will be McLaughlin's goal at Dartmouth, where tensions over the changes of the past decade still linger.

McLaughlin's close identification with both Dickey and Kemeny may, in fact, be the strongest asset McLaughlin brings to his Parkhurst Hall office. His thinking on education and his feelings for Dartmouth were molded equally by Dickey and by In 1954, when "King" McLaughlin was stilla student, a prescient Alumni Magazine writer was calling him the people's choice.

Kemeny - one man a lawyer and diplomat, the other a mathematician. McLaughlin's instincts, moreover, may run more to consolidation than to innovation. As an outdoorsman and athlete, he can reach out to those who prize the fellowship wrought from four years in Hanover. As a Phi Beta Kappa scholar, he can appeal to those committed to maintaining increasing, even - the value of the Dartmouth diploma. And as a member of the Board of Trustees that brought women and a commitment to affirmative action to Dartmouth, he can speak to those concerned about the place of minorities at the College.

These divisions and the single-interest groups that have come to symbolize them rank high among McLaughlin's concerns. "Many feel that the College has altered its allegiance to its heritage," he says. "I don't believe that's true. Going coeducational, for example, was not a repudiation of that heritage; it was a necessary development to insure that heritage. Otherwise, Dartmouth wouldn't have attracted the kinds of students you need to maintain that heritage. The College its goodness, its grace, its sense of humanity hasn't changed. And they will be reinforced."

"It's a hard thing to do," he says, "but Dartmouth has always had a commonality of interest. I don't see people focusing on that common interest as clearly as they might. It needs some leadership and presence."

Presence, in fact, is a word that turns up often among McLaughlin's associates. "He's got a lot of presence," says Mark Willes, the chief financial officer at General Mills and a member of the Toro board, "and as a result he will do an exceptionally good job fitting into an intellectual, academic community." Adds Martin Friedman, director of the highly regarded Walker Arts Center of Minneapolis: "He's a reasonable and deliberative individual, able to assess a situation quickly. He sets goals and gets to them. He'll bring a whiff of the real world to the tucked-away isolation of Dartmouth."

By all accounts, McLaughlin who is 49, six years older than Kemeny was when he took office is possessed of indefatigable energy. As a student he was known for studying ten hours at a sitting and was, according to a classmate, "completely oblivious to distraction." The corporate boardrooms around Minneapolis likewise yield their McLaughlin stories. He usually gets up before dawn, is in his office by seven, and takes work home with him each evening and over weekends. "He's got a high, high activity level," says David L. Mona, a Toro vice president who was discharged during the company's retrenchment this spring. "No matter where he travels he manages to get papers on your desk by 7:30 in the morning. He ran a schedule around here that kept two secretaries busy fulltime."

Now McLaughlin is ready to harness that energy for what he soberly calls the "unparalled challenge" that private education faces in the 1980s. He points to declining enrollments nationwide and to the steady levels of inflation and worries that together they may erode the integrity of the historic College. In a commencement address delivered at Heidelberg College in Ohio two years ago, McLaughlin gave some hints of his concern for the future of liberal arts institutions, warning that colleges must "retain the values and strengths of [their] heritage while still adapting to a very rapidly changing environment."

THE choice of a businessman over an academic for the presidency of an Ivy League institution is unusual but not unprecedented. Sixty-five years ago, in 1916, Dartmouth became the first New England college to select a businessman as its president when Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, a telephone company executive, was selected to succeed Ernest Fox Nichols, a noted physicist. "He is essentially a businessman," the Seattle Times said of that appointment, "and his administraion may reveal to Dartmouth and other institutions of learning a way to render a better and broader and more effective service in their relations to the practical side of life." By the time his 30-year presidency was over, however, Hopkins was known as the man who gave Dartmouth a national academic reputation.

"I think the theory is all bunk that you get a greater interest in academic affairs and in the purposes of education from ministers and teachers than you do from businessmen," Hopkins wrote in 1924. Those who know McLaughlin agree he has thought deeply about Dartmouth's commitment to superior liberal education. Dartmouth under McLaughlin can be expected to grow little quantitatively, but the new president hopes to spur quantum leaps in the quality of the Dartmouth education.

"Dartmouth's strength," says McLaughlin, "is that it is a university that's good enough to be called a college. But I want to have Dartmouth on the forefront of scholarly thinking. We've got to become known for a high level of relevancy in society and to be on the front edge of how to think about issues in this society. It means the campus can be much more alive in terms of thinking and research."

Nonetheless, the faculty remains divided over the choice of McLaughlin, with several faculty members fearful the selection of a businessman is a signal the College may no longer give first priority to academic matters. "What are we supposed to think," asks one professor, "when they go ahead and choose the head of a company to run a college? Where does that leave us?" "I was disappointed," says another, "not because of what he was but because of what he wasn't. He wasn't an academician." Overall, however, those faculty members who oppose the McLaughlin selection are more apprehensive than hostile. And, as one professor notes, "this may mean the faculty may be left to decide faculty matters."

None of the controversy surprises Charles T. Wood, a former St. Paul, Minnesota, investment banker who now is Daniel Webster Professor of History at the College. "This is to be expected," says Wood. "It may take three or six months of getting used to each other, but McLaughlin absolutely will convince all the doubters. When Kemeny announced his resignation last year, Dave was the first person who occurred to me. As the chairman of the trustees and a businessman, I knew he'd be a dark horse, but we're lucky he was chosen. It's a great choice."

McLaughlin himself anticipated the criticism and has already moved to assure the faculty he sympathizes with their tenure, salary, and scheduling problems. He has asked the faculty for its cooperation and, for his part, has promised to listen. "I'm very much aware of their feelings, and I can understand them," he says. "I know I have a tremendous amount to learn, but I'm comfortable in the setting of a faculty renowned for its teaching abilities."

At the same time, McLaughlin believes more businessmen will be chosen for college presidencies as economic and demographic factors put private education in jeopardy. "Over the next decade without growth, without more federal assistance, and with more competition in raising funds there are going to be some very tough challenges," he says. "There's going to be a trend toward putting management acumen in partnership with academic excellence. I don't think education has distinguished itself in finding creative answers to its problems. In fact, one of the only creative ideas that has come out of education is something John Kemeny did: year- round operation."

Whether businessman or academic, McLaughlin seems well suited to the rhythm of life in Hanover. Both David and Judy McLaughlin are knowledgeable of the arts and interested in them. They enjoy outdoor activities, particularly winter sports. And they are aware of the importance, as Dickey so often put it, of the sense of place: They grew to know the white owl who sat in their trees in Minnesota, the family of foxes that used to traverse their land, and the raccoons who visited their back step.

Judy McLaughlin, especially, will find a comfortable niche in Hanover. Newly married, she and her husband lived off the Lyme Road while he finished up at Tuck. Today she ministers over her flowers and vegetables and perennially is a blue-ribbon winner for her flower arrangements. In Hanover, she will likely slip into a psychology class or two, and then invite the student in the next seat to join her in a few sets of tennis. And she is the type of woman who will turn up at soccer practice just to watch, and to enjoy the leaves turning on Balch Hill in the autumn.

The McLaughlins, in short, speak so easily of the "Dartmouth family" because they are a Dartmouth family. Bill graduated in 1978 and is completing his M.B.A. at Tuck. Susan lives on the second floor of Topliff and graduates next month. And Jay, who finishes at Phillips Andover this spring, will be a freshman in September; his only worry is that he will be invited to the College president's home too often for dinner.

MCLAUGHLIN considers Dartmouth's financial position sound and its investments prudent. But he believes that without the success of the Campaign for Dartmouth now underway, the College will be unable to retain its excellence and avoid drawing off the principal of its endowment. Apart from strictly financial concerns, McLaughlin plans to do some fine tuning in the operation of the College. He has plans already applying new management techniques, upgrading Dartmouth's accounting systems, applying the computer to even more administrative tasks. These are ideas he likes to talk about, for McLaughlin sculpts his projects verbally. It is an animated process: He takes an idea, turns it over, adjusts it, tries it again, tunes it. . . .

He's not yet fully comfortable talking publicly about the management changes he will implement. But one thing can be sure: Changes will be made. "Any institution dependent upon money from outside individuals must assure its donors it is managing that money in a highly prudent, professional manner," he says. "We can be more efficient and more productive."

Despite recent losses at Toro, McLaughlin is widely regarded as one of the wunderkind of the management and finance world. Just ten years after shaking Dickey's hand at matriculation, McLaughlin had worked himself into the presidency of a subsidiary of Champion Paper Inc. At age 38, he was recruited to become the president of Toro.

SELLING lawn-care equipment in the summer and snowthrowers in the winter, Toro under McLaughlin increased its sales from $57 million to $403 million. Under his leadership, the company broadened its price ranges and reaped the whirlwind of the heavy snows of 1977 and 1978, when Forbes magazine credited McLaughlin with turning Toro into "one of the year's hottest growth .items."

The profits, however, have vanished with the snows of yesteryear. There is no more telling gauge of Toro's fortunes than the snowfall chart in the corporate headquarters, a gleaming gold building in East Bloomington, Minnesota, known as One Appletree Square. There, on the eighth floor, the company conducts an informal pool, with employees guessing the date by which snowfall in the MinneapolisSt. Paul area reaches the rather modest level of 40 inches. This year nobody won.

This season's low snowfall was particularly damaging because it followed a winter in which similarly low snowfalls left Toro with an unsold inventory of 350,000 snowthrowers. Even the fake snow that descended upon the Minneapolis Children's Theatre during last December's annual stockholders' meeting did little to brighten the company's balance sheets. The company has reported losses of more than $10 million in the past nine months.

Analysts agree that Toro was, in part, a victim of its own success. Unusually large snowfalls toward the end of the decade helped lift snowthrower sales from $17.6 million in fiscal 1976 to $119 million in fiscal 1979. With the large snowfalls from Boise to Buffalo to Boston came criticism from dealers and distributors who couldn't keep up with consumer demand. "Listening to these complaints was the start of Toro's woes," wrote Dick Youngblood in the Minneapolis Tribune, "for the company immediately started beefing up to meet the demand." Toro doubled its snowthrower production in the 1979-80 season and nearly doubled its salaried employment in the span of two years. Snow levels dropped, interest rates soared, and though sales did rise nine per cent, they did not begin to keep up with the rises in production.

In February, just as Dartmouth's presidential-search committee was narrowing its choices, McLaughlin implemented stiff cutbacks at Toro, firing the company's president and three senior vice presidents and releasing 125 salaried workers. He imposed sharp reductions in production, eliminating 200 factory jobs by closing two of Toro's three manufacturing plants in Hudson, Wisconsin, and extending the summer layoffs for 2,000 workers in Toro plants scattered about Minnesota and Wisconsin. The company's board of directors, with the knowledge that McLaughlin himself might soon leave for Dartmouth, unanimously supported the moves.

"These were things we would have done regardless of what my future plans were," says McLaughlin. "We took the tough corrective steps for the long-term growth and development of Toro."

Then came the Dartmouth offer. It was not entirely unexpected, though McLaughlin had urged the search committee to choose a president with academic credentials. Coming less than two weeks after the shake-up at Toro, it was a classic case of bad timing, but McLaughlin could control the timing of the offer no better than he could control the weather. The decision had to be accepted or rejected now; it never would come again.

Uncharacteristically, McLaughlin was filled with doubt. He knew his background as a businessman would not win him favor with the faculty. He knew the move from a dirt road to Webster Avenue would unsettle his personal life. And he knew that accepting the Dartmouth presidency would fuel talk unfairly, he thought that he was fleeing a bad situation at Toro.

In the end, of course, he took the job, and the heat. "I don't think I'm running away from anything," he told the New York Times, which dispatched a reporter to Minnesota to listen to the whispering in the Minneapolis Club. "I'm satisfied I'm not leaving a troubled ship. It's in capable management hands."

Minneapolis observers and analysts tend to agree. "The brand name," said one, "is in good shape." Adds William A. Andres, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of the Minneapolis-based Dayton-Hudson Corporation, "I don't see how the vagaries of the weather are any reflection of his abilities at Toro. Until the snow problem he was doing an exceptional job. Into every company some rain must fall, and Dave handled the Toro situation extremely well."

The Dartmouth offer in hand, McLaughlin summoned the Toro board and delivered the news they had all halfexpected for months. Several sources confirmed. that the board was unanimous in its support of McLaughlin. At least one board member tried to persuade McLaughlin to turn down the offer. But the pull of Dartmouth was too strong, as the board members knew it would be; they knew that McLaughlin would, as Dickey said of Hopkins, choose to serve his college. "A man's got to decide what he thinks the right move is," says General Mills' Willes, a member of the Toro board. "I think the board feels that way, too."

AND so it is done. David McLaughlin, son of the College, is coming back to Hanover, though not as a freshman driving through the mountains, for the first time, a duffel bag stuffed in a friend's car. He will be cautious at first; that is his style. "I've got some ideas," he says, "but between now and June 28 I'm going to try and sit and listen. I want to test my own feelings and perceptions. I want more than my own agenda. I want an agenda that reflects the broad constituency of the College, and I want the time to think through some of the solutions."

He'll think about the quality of social life on campus, which he regards as too intimately linked with drinking. He'll think about sports, which he believes have value beyond the team standings. He'll think about providing a strong intellectual culmination to the college years, which he found so useful during his own Great Issues course. He will think, and listen.

"There is a lot of difference," said Ernest Martin Hopkins, "between a college presidency as a profession and as a mission." That choice, as McLaughlin's friend Dickey might say, will be made for him only if it is made by him. The future will tell. But as president of the College, McLaughlin hopes to bring back to Dartmouth the elements he took away from it a sense of confidence, a way of looking at issues and problems in broad perspective, the ability to ask important questions and, finally, a warm, enduring sense of belonging. For it is these things that drew David McLaughlin back.

Yet it is more than nostalgia that attracts him back to Dartmouth, and it will be more than nostalgia that McLaughlin hopes will retain the loyalty and financial support of its sons and daughters. Here the goals of the businessman and the educator converge: "The College's alumni have supported Dartmouth out of a loyalty to the College and a feeling of debt for what the College gave them. In the next decade, though, we have to reinforce more clearly the importance of healthy, private liberal-arts colleges. Dartmouth is an institution of real value, and money channeled toward it will produce something of real value. It isn't just a matter of loyalty and nostalgia. It's a matter of excellence."

A new age now begins. John G. Kemeny, perhaps the most innovative president in Dartmouth's history, is passing the badge of office, the 200-year-old Flude Medal, to his successor. It is a historic moment in the life of the College. In 1916, 20 college presidents and delegates from 45 other institutions gathered in Webster Hall for the Hopkins inauguration. Dickey, who was inaugurated in the faculty room of Parkhurst Hall, and Kemeny, who was inaugurated in Alumni Gymnasium, chose less regal proceedings. McLaughlin will follow suit. His inauguration will be a lowkey, family affair, befitting the man.

Flanked by the leather case containing the College Charter and the silver bowl John Wentworth, the royal governor of New Hampshire, presented to Eleazar Wheelock, McLaughlin will take his place in the Wheelock Succession. It is one of the most ancient, yet most austere, ceremonies the College has. And as McLaughlin stands before the gathering on the lawn of Baker Library, he may reflect on the words of Daniel Webster, delivered a year after he argued in front of the Supreme Court for the survival of his college: "Our College cause will be known to our children's children. Let us take care that the rogues shall not be ashamed of their grandfathers."

Judy McLaughlin will find her neighbors on Webster Avenue noisier than thedenizens of the Minnesota woods. She joined her husband on an inspection tour in April.

David Shribman '76, who interviewed thepresident-elect in Minnesota in March, is awriter for the national staff of theWashington Star.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

David Shribman

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHIS HAT

June 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMurray Hitzman '76

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureZen and the Art of Corporate Maintenance

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

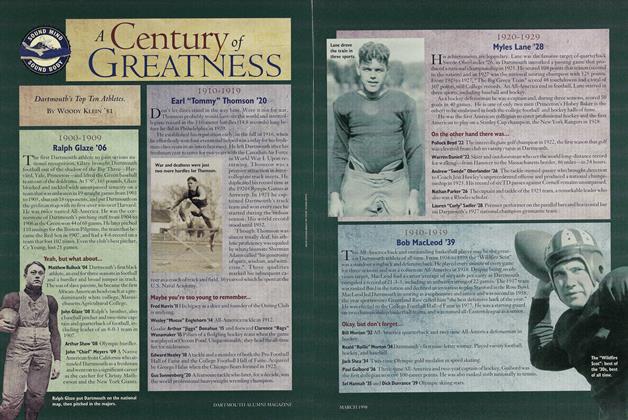

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51