No Dice

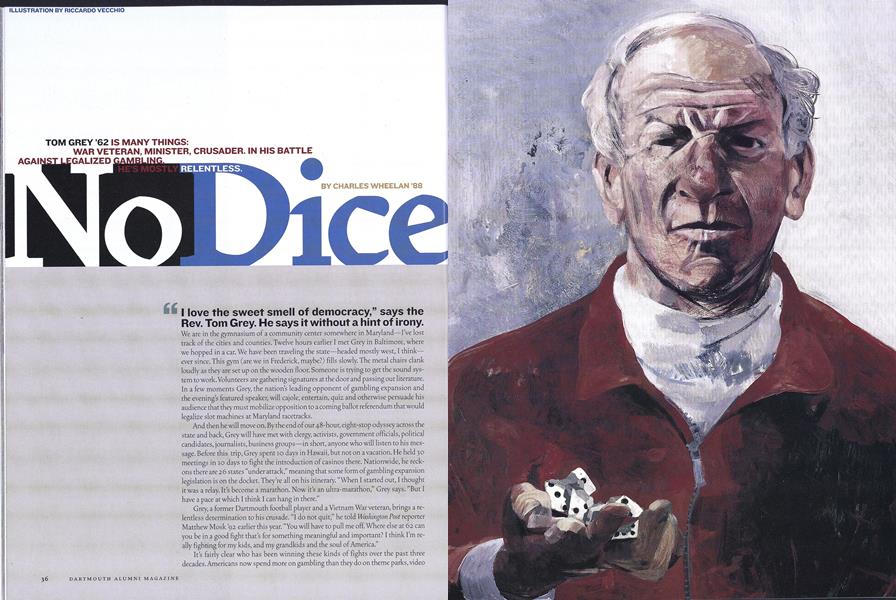

Tom Grey ’62 is many things: war veteran, minister, crusader. In his battle against legalized gambling, he’s mostly relentless.

July/Aug 2003 Charles Wheelan ’88Tom Grey ’62 is many things: war veteran, minister, crusader. In his battle against legalized gambling, he’s mostly relentless.

July/Aug 2003 Charles Wheelan ’88TOM GREY '62 IS MANY THINGS: WAR VETERAN, MINISTER, CRUSADER. IN HIS BATTLE AGAISTLEGALIZED GAMBLING. HE'S MOSTLY RELENTLESS.

I love the sweet smell of democracy," says theRev. Tom Grey. He says it without a hint of irony.

We are in the gymnasium of a community center somewhere in Maryland—l've lost track of the cities and counties: Twelve hours earlier I met Grey in Baltimore, where we hopped in a car. We have been traveling the state—headed mostly west, I think- ever since. This gym (are we in Frederick, maybe?) fills slowly. The metal chairs clank loudly as they are set up on the wooden floor. Someone is trying to get the sound system to work. Volunteers are gathering signatures at the door and passing out literature. In a few moments Grey, the nations leading opponent of gambling expansion and the evening's featured speaker, will cajole, entertain, quiz and otherwise persuade his audience that they must mobilize opposition to a coming ballot referendum that would legalize slot machines at Maryland racetracks.

And then he will move on. By the end of our 48-hour, eight-stop odyssey across the state and back, Grey will have met with clergy, activists, government officials, political candidates, journalists, business groups—in short, anyone who will listen to his message, Before this trip, Grey spent 10. days in Hawaii, but not on a vacation. He held 30 meetings in 10 days to fight the introduction of casinos there. Nationwide, he reckons there are 26 states "under attack," meaning that some form of gambling expansion legislation is on the docket. They're all on his itinerary. "When I started out, I thought it was a relay. Its become a marathon. Now it's an ultra-marathon," Grey says. "But I have a pace at which I think I can hang in there."

Grey, a former Dartmouth football player and a Vietnam War veteran, brings a relentless determination to his crusade. "I do not quit," he told Washington Post reporter Matthew Mosk '92 earlier this year. "You will have to pull me off. Where else at 62 can you be in a good fight that's for something meaningful and important? I think I'm really fighting for my kids, and my grandkids and the soul of America."

It's fairly clear who has been winning these kinds of fights over the past three decades. Americans now spend more on gambling than they do on theme parks, video games, spectator sports and movie tickets combined. All but two states now permit some kind of wagering. lowa is a typical case. In 1972 a Catholic priest was arrested in Dubuque for sponsoring a bingo game. Thirty years later the state has 10 riverboat casinos, three Indian casinos and three racetracks with slot machines.

Still, the organizations Grey leads—the National Coalition Against Legalized Gambling and its political arm, the National Coalition Against Gambling Expansion—can claim some striking victories. "It's our people against their money and muscle," says Grey. Hawaii said no to casinos. New Hampshire voted down slot machines. A referendum to ban the video lottery in South Dakota failed narrowly, 48-52; the narrow margin indicated that many voters were willing to forego gambling even though that would have required the largest tax increase in the states history. When it comes to his referendum battles, Grey claims a 20-2 record prior to September 11. Since then, he says, states' budgets have made legislators desperate, and their hopes for new revenues make Grey's tough job even tougher.

Greys organizations have a combined annual budget of $140,000; the American Gaming Association, led by former National Republican Party chair Frank Fahrenkopf, has a $4 million "annual budget.The United Methodist Church provides Grey with a meager annual stipend of $36,000, plus $600 per month for travel expenses. "My wife always says: 'Tom, don't you ever get discouraged?' because every time we win, they come back. This is like Nightmare on Elm Street. But I'm one of these fun people that the more I get in it and the more I know I have the truth and the more you keep coming on me, the harder I hit back," Grey says.

By the time we reach our sixth or seventh stop, a church meeting in the foothills of Appalachia, I know Grey's spiel pretty well. It's folksy and funny, and oddly charming. He pulls out his snake oil jar to represent the gaming industry's promises. "They say gambling is family entertainment," he tells the audience. And then, with the exquisite timing of a stand-up comedian, "So why are there 64 pages of escort services in the Las Vegas yellow pages?" Soon he will wave a report on the economic benefits of gaming that has been prepared, fortuitously for him, by Arthur Andersen. "You know Arthur Andersen, right? They're the folks who brought us Enron." More laughter.

Beneath the surface is a stone cold strategy. By the time we reach western Maryland, when we are nearer to Gettysburg than Baltimore, Grey points out that the North won the famous Civil War battle by staking out the high ground. If you pick the battle and decide the terms of the battlefield, he says, then you can determine the outcome. Grey always chooses his battles carefully. He never mentions the word sin, even when he is alone with clergy. "If you attack gamblers, they will fear us," he tells them. "Go after the product and the promises." In his standard pitch, Grey goes on to say gambling makes losers of citizens, sucks money out of local businesses and creates despair in communities.

His audiences are often skeptical, particularly in areas where more gambling has been advertised as a painless new revenue source. The same questions tend to come up: "If our citizens are driving across the river to gamble in West Virginia, why shouldn't we keep the money over here?"

Grey shoots back, "Mug'em here before they get mugged there? That's good government. That's enlightened."

Or what about the new jobs? "Gambling creates 22 gambling addicts for every new job," he answers. "Would you welcome any other industry that makes victims of 5 percent of your community? Would you allow a factory that gave 5 percent of your people cancer?"

Grey does a lot of preaching to the choir, too—girding them for the battles they will have to lead long after he has flown on to another state. One of his meetings in Maryland is at the tiny St. Paul Community Baptist Church, a pleasant building in an otherwise rundown section of Baltimore, where a handful of the faithful gather to give him the lay of the land. "Tell us your strengths. Where do you have people?" Grey asks. He ticks off the natural allies they should be seeking: law enforcement, chambers of commerce, the restaurant association, the mental health community, the editorial pages of The Baltimore Sun. "You've not come together with a strategic plan that involves the state," he admonishes them.

Grey and his supporters will succeed in Maryland, or anywhere else, only if they can cobble together a coalition of groups—many of whom would agree on virtually nothing besides the need to oppose gambling—and bring that force to bear on the political process. "When I fight, I want a network," Grey says. "I want liberal, I want conservative, I want Republican, I want Democrat, I want all my bases covered. That's why we never talk about anything but gambling, because if you start to talk to one another about other issues, you'll all go out other doors. This issue unites people who fight each other on other things."

Grey stays with supporters, flies Southwest Airlines and revels in the journey. "Are we having fun yet?" he likes to ask at the end of his meetings. He says he learned two things at Dartmouth: how to play poker and how to take a road trip. It's a good line, given that his current life consists of doing the latter to fight the former. But poker? It may seem surprising to learn that Grey sees gradations in gambling. In his view, slot machines represent the greatest evil. Table games aren't as bad; in fact, games such as poker even have a worthy social component, according to Grey. He would be happy if his battle against gambling expansion led to a return to only table games. Grey calls this a "Hollywood ending" scenario for his fight, since table games provide jobs and entertainment and are far less addictive than machines.

Dartmouth was actually a much richer experience for Grey than poker and road trips. He arrived in Hanover from the placid Chicago suburb of Arlington Heights. He played football and enlisted in ROTC "because it was the kind of thing one did back then." An injury during sophomore year ended the football, and the College became a more interesting place as a result. "I was a Midwestern kid who probably didn't picture himself being a person who could go anyplace and do anything, in terms of limits, and Dartmouth opened everything up," he says.

Grey was elected president of Beta Theta Pi in 1961, just as racial issues in the fraternity system were coming to a head. That summer the Beta house had voted to break with the national organization over its policy excluding blacks. The Beta national, in turn, was threatening to sue the breakaway Dartmouth chapter and dispatched James Moreau Brown, a prominent business executive from the class of 1939, to campus to underscore the threat. Grey recalls being summoned along with Brown to the office of Dean Thaddeus Seymour, who, in what Grey describes as "an exquisite moment," said: "Mr. Brown, what I want to tell you is that you're not suing Beta Theta Pi—this Beta house—you're going to be suing Dartmouth College." In the end, Beta blinked.

Grey entered the Army after graduation. In 1966 he was sent to special warfare school and then shipped out to Vietnam. I went over with rose-colored glasses and came back with a thousand-yard stare," he says.' He married his wife, Carolyn, while on leave in Bangkok. (The wedding cake was inscribed with the words "All the way," the motto of his airborne unit, though his bride interpreted the message differently and was reduced to tears.) They now have two grown children. Carolyn endures her husbands peripatetic lifestylemore than 200 days a year on the road—with remarkable equanimity. "When I'm home, I'm really home," Grey says.

Grey's involvement in the gambling issue came late in his career, almost by accident. After he'd spent two decades as a minister, mostly in racially mixed, poor parishes in the Chicago area, the local Methodist bishop sent him to a parish in Galena, a picturesque Illinois town on the Mississippi River about 80 miles from Grey's current home in Rockford. When a riverboat casino was proposed as an economic development strategy for the area in the early 19905, Grey, who had seen enough gambling in his life, both as a minister and a soldier, knew that he wanted none of it. He organized opposition and succeeded—almost. In 1992 residents voted overwhelmingly against the riverboat, but the election was advisory, and the county commissioners voted the riverboat in anyway. "That's when I got really mad," Grey recalls.

After that, it was just a matter of negotiating flexibility with the bishop and answering the phone. In 1993 Indiana was considering gambling expansion. In 1994 it was Missouri. Ive sort of ridden the wave of gambling expansion," Grey says.

Its not clear where that wave ends. Grey says hes having fun and fighting a good fight. "I'll know this job is over when I don't get any calls," he says. Then he reflects for a moment and adds, "Or I get a lot of calls and I say 'I don't want to do this.' " As we roll back into Baltimore, sometime around midnight, I get the sense that neither is likely to happen anytime soon.

I'm going home. Tom Grey is headed to Missouri.

Grey Matter The media-savvy minister, here making a point to supporters, has appeared on 60 Minutes and in the pages "of Time, People,The Wall Stree Journal and other publications.

CHARLES WHEELAN is a public policy analyst in Chicago and theauthor of Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science

"When I fight, I want a network. I want liberal, I want conservative, I want Republican, I want Democrat, I want all my bases covered. This issue unites people who right each other on other things."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

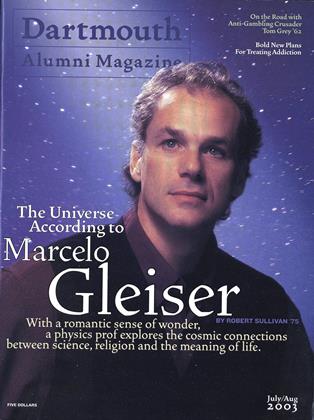

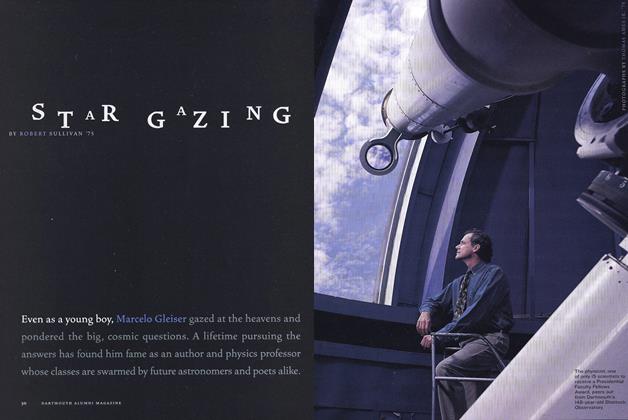

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July | August 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July | August 2003 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Big Day

July | August 2003 By Julie Shane '99 -

Article

ArticleFighting Addiction

July | August 2003 By Julie Sloane '99 -

Interview

Interview"A Diversity of Ideas"

July | August 2003 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFuture Action and Planning

APRIL 1959 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

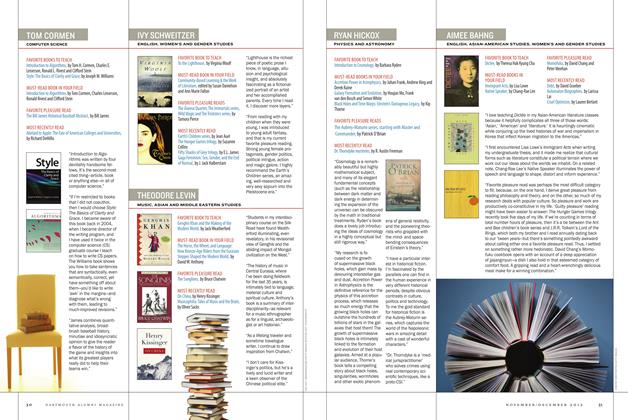

FeatureTOM CORMEN

Nov - Dec -

Cover Story

Cover StoryEDWARD TUCK’S POCKET WATCH

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORY“Out of Crisis Comes Opportunity”

MAY | JUNE 2016 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.